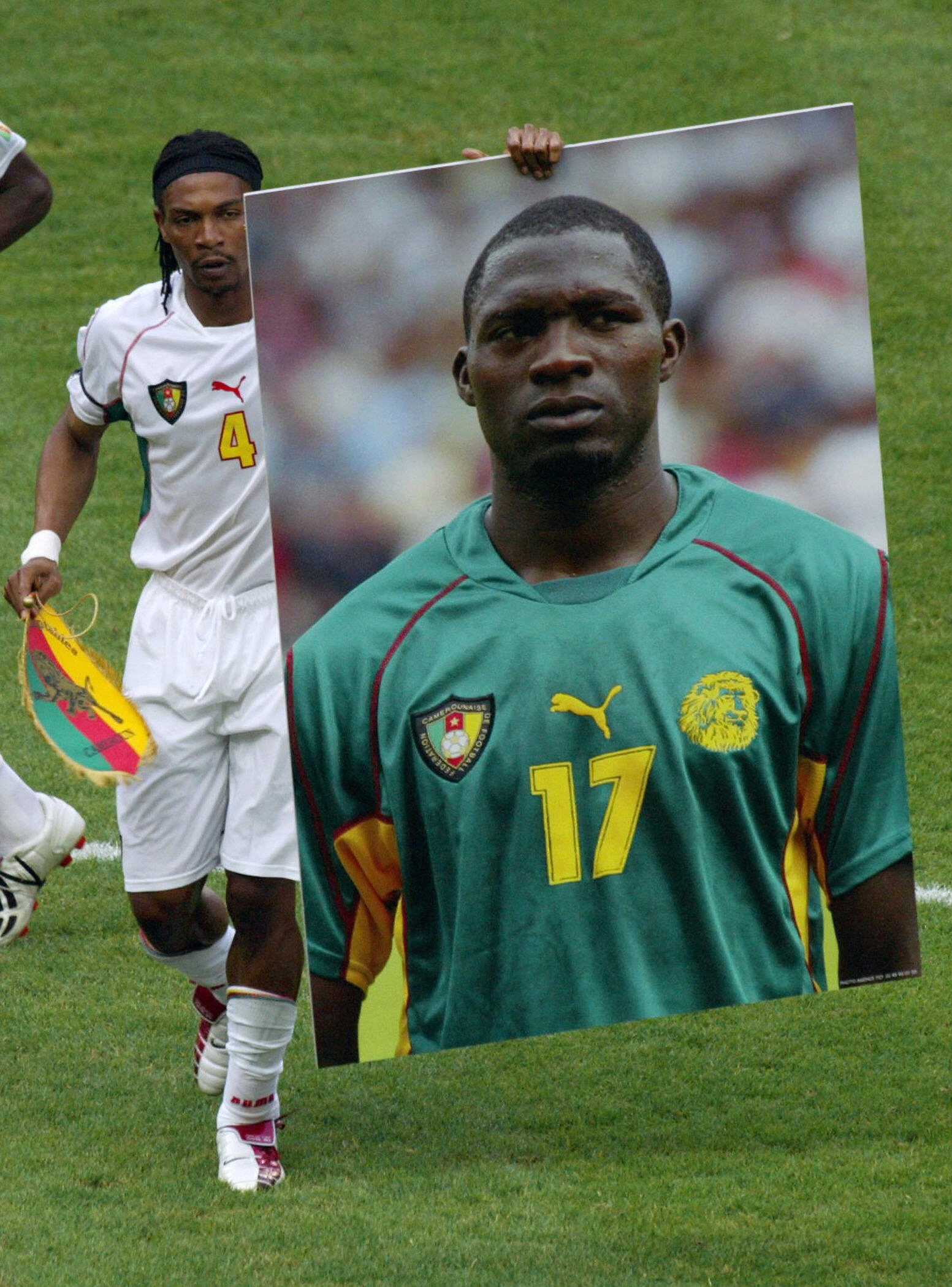

The inspirational life, tragic death and legacy of Marc-Vivien Foé

This piece was written by Njie Enow for Issue 44

“Even if it means someone has to die, we have to win this game,” Marc-Vivien Foé said to his teammate Eric Djemba-Djemba as the Cameroon team bus made its way to the Stade Gérland for the 2003 Confederations Cup against Colombia.

Djemba-Djemba was listening to music. “I’ve made a promise to my wife and kids that we’ll win this game and win the Confederations Cup,” he replied. He didn’t take Foé’s words seriously: players say all kinds of things in the hours before kick-off.

With Foé lubricating the midfield, Cameroon played well and led through Pius Ndiefi’s 7th-minute header when, with 18 minutes remaining, Foé collapsed near the centre circle.

At full time, in the corridor leading to the dressing rooms, there was screaming and a lot of laughter. Cameroon had become the first African side to reach the Confederations Cup final. It was a chance to atone for having gone out in the group stage at the 2002 World Cup, despite having won the previous two Africa Cups of Nations.

But the mood changed when their coach Winfried Schäfer came into the dressing room. “I’m afraid I have some bad news,” he said. “Something terrible has happened and Marco [as his teammates called him] didn’t survive. He’s dead.” Foé had suffered heart failure on the pitch and 45 minutes of attempts to save him had failed. An autopsy would later reveal that his death was caused by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a condition in which the heart becomes thickened without obvious cause, making blood circulation difficult.

In Yaoundé, 4,200 miles from Lyon, street celebrations were quickly replaced by sadness as news of the tragedy spread. In Essos, the neighbourhood where Foé grew up, pubs and bars closed quickly. Fans wept in the streets. Throughout the evening, Cameroon’s state radio CRTV broadcast a 10-minute interview with Foé, the last he had given before departing for the Confederations Cup.

In it, he spoke excitedly about a fruitful spell at Manchester City and the qualities of the Cameroon team. Foé’s enthusiasm had always made him a fan favourite.

Marc-Vivien Foé was born in Yaoundé on 1 May 1975. He was robust and physically imposing, always athletic, but he had been raised a Roman Catholic and for a time seriously considered entering the priesthood, attending the Sacred Heart College at Makak in central Cameroon. The institution’s mix of education and sport would led Foé in another direction: football. “That I played football was God’s work,’ he said in 1994 when he joined the French side Lens. “It was all a miracle.”

He started out, though, at Union of Garoua in the north of Cameroon, where he impressed enough in a brief stint to earn a move to Fogape of Yaoundé. Although they were a second-division side they had a reputation for developing young talent and every training session at the dusty annex to the Stade Ahmadou Ahidjo would be attended by scouts from local giants and, at times, foreign teams.

By the time Foé turned 17, he had done enough to draw admiration from Canon of Yaoundé, one of the giants of the Cameroonian game. Although they had won four club continental titles in the 70s and 80s, Canon were in a slump and desperate for fresh talent to get them firing again.

Their coach was Jean Manga Onguené, a Canon legend as a forward and the 1980 African Footballer of the Year. He had won 16 titles with the club between 1966 and 1982 and was tasked with masterminding a continental renaissance. He saw Foé integral to this plan.

Onguené asked his captain Jules Denis Onana to organise Foé’s move. An extremely talented defender nicknamed ‘the Professor’ by fans, he had been part of the Cameroon squad that had reached the quarter-finals of the 1990 World Cup. “Our coach Manga Onguené told me that Foé could be the next big thing from Cameroon,” Onana recalled, “and he insisted I had to negotiate with Foé because he felt the young man would listen more if I did the talking.”

Foé’s first training session confirmed Onguené’s judgement as the teenager demonstrated an acumen beyond his years. “That boy was simply wonderful,” Onana said. “He had such an amazing understanding of the game that he could play anywhere on the pitch.

“He was so good that the coach used him in several positions and he fared well. We used him at centre-back and wing-back when we had a few injuries, and deployed him in the midfield. He adapted so well and with him on the pitch we could easily switch our game plan.”

Foé’s first derby against Tonnerre Kalala at the Ahmadou Ahidjo came in 1993. Racing of Bafoussam had been a surprise league champion the previous season and looked like retaining their title. The build-up was feisty, with Tonnerre promising devastation. They were led by the veteran striker Roger Milla. Even at 41, the two-time African Player of the Year was as strong as a stallion and had been in fine goal-scoring form.

Foé’s job was to keep Milla in check. In the first half, the youngster dominated the legend. “I have a lot of admiration for Milla and I’m learning how to defend against him,” Foé told reporters at half-time. “He’ll find me every step of the way in this game.”

But Milla still had some tricks up his sleeve. Canon led 2-1 and seemed comfortable when Milla evaded Foé on the edge of the box and lashed home to convert a counter-attack and earn Tonnerre a draw. Foé felt he could have done better, but he had done enough to endear himself to fans and coaches, as well as win a spot in the Cameroon squad for the 1994 World Cup in the USA.

September 1994, after Cameroon’s disastrous World Cup campaign. Foé is in a room in northern France talking to reporters. He’s just joined the French top-flight club RC Lens on a five-year deal after rejecting an offer from Auxerre. “I’m a very timid person and I don’t bother about what is happening around me,” Foé said. “Football is a gift from God because I never had a start; it just happened.”

Foé spent five seasons with Lens, winning a French league title in 1998. His heroics caught the attention of Sir Alex Ferguson, who was keen on signing him for Manchester United. A broken leg and disagreement over the player’s valuation saw the deal called off before the 1998 World Cup.

The West Ham manager Harry Redknapp had long been an admirer of Foé and signed him in 1999. “Marc was a fantastic friend and I keep lots of fantastic memories of him,” said his former teammate Paolo Di Canio. “He was an incredible friend, a family man who always took up responsibilities when he was needed.

Di Canio joined West Ham at the same time and has a photo of the two of them together, smiling as they hug each other. “He was a tremendous player,” Di Canio said. “There was a week when it rained consecutively for three days in London and we had a training session in the morning. Our manager Harry Redknapp wasn’t very sure if we could train with the downpour.

“So all the players gathered around the pitch and Marc was at the other end. It was very cold and suddenly we saw someone run out of the dressing room naked with his boots on. Initially we didn’t know who it was, then we looked closely. It was our mate John Moncur and he was screaming, ‘Come On! Come On!’

“Instinctively, I lifted my head and caught Marc’s gaze. We both started laughing and we thought John Moncur was mad. Marc’s smile was contagious and he was truly a good man.”

It was sometime around March 1993. Cameroon’s under-20 men’s side had just returned from the World Youth Championship in Australia where they had been knocked out in the group stage. Foé, aged 17, had featured in all three games, scoring in a 3-2 defeat to Colombia.

The team’s return to the country was announced on the national radio and while most members of the side had been spotted, Foé hadn’t been seen by his family and friends. His parents became increasingly worried: where was he? Had he decided to remain in Australia?

His mother had dispatched his cousins and uncles to track him down. When they found him, he was surrounded by children at an orphanage to which he had donated his earnings from the tournament. “Helping others meant a lot to him,” said a family friend. “He always felt it was his responsibility to help the needy. There were times when he received his fees, he’d tour the various orphanages and hospitals to see if there was something he could do. Whenever Foé was in Yaoundé, if he wasn’t at home, the surest place you could find him was in one of those orphanages.”

Foé’s desire to help the underprivileged was insatiable. It was, he felt, the best way to display his gratitude for what he described as “God’s blessings”.

Alongside that sense of responsibility off the pitch was an authority on it. “He was the team’s brain,” said the former Tottenham defender Timothée Atouba, a teammate at national level. “He incarnated all of the side’s values. The team’s captain was Rigobert Song but we all knew that when things weren’t going on well, we’d turn to Marco and there would be a solution.

“I joined the national team when I was 17. Very often what happens is you have people always trying to intimidate you and break you as a youngster but Marco was the guy who made sure that we were covered. He’d show up in our rooms to ask if the youngsters who joined the national team like myself or Samuel Eto’o were all right. He was an amazing leader and he made us feel at home.”

Foé had an aura of invincibility that helped bring consecutive continental titles in 2000 and 2002 and Olympic gold in Sydney in 2000. The French coach Pierre Lechantre, who led Cameroon at the 2000 Africa Cup of Nations, was concerned there was so

much quality and so many options that the competition within the squad could damage their chances. He relied on a midfield trio with Foé at its heart.

“On the pitch, he was a key player,” he said. “He was the shield to the defence and breathed life into our attack. Marco was so good that at times I didn’t even have to say a lot. When you have Rigo [Rigobert Song], Marco and Patrick [Mboma] on the pitch, you can trust them to execute [ideas] properly and bring the others back to order if things didn’t go well as planned.”

Lechantre led Cameroon to their third African title in 2000, their first in 12 years. He was succeeded before the 2002 tournament in Mali by the German Winfried Schäfer. One thing remained constant: Foé’s influence and his ability to dictate the pace of the game as well as provide an identity for the team.

“Foé was the captain’s captain,” said Rigobert Song who skippered Cameroon from 1998 to 2009. “We knew each other as kids, growing up in Yaoundé and from a young age he was charismatic,” he said. “Our paths obviously crossed a lot. We were two teenagers playing for the two biggest clubs in Cameroon.

“He wielded so much influence that at times before I took certain decisions, I consulted him first. He was an incredible player and you got the feeling that he had a crystal ball in his hands because before the ball got to Marco, he knew what he was going to do with it.

“He died in 2003 and look at how much we suffered after he left. We missed a World Cup qualification in 2006 and had two not so good Cup of Nations competitions in 2004 and 2006. We had very good players come through but I doubt we have had anyone of Foé’s calibre.

“Foé was unique, he was everything a teammate will wish for and everything a coach could dream of.”

Foé had joined Lyon in 2000 and despite his spell with the club being blighted by malaria, he played 43 games and scored three goals as he helped secure the French Cup in 2001 and the Ligue 1 title a year later. The Confederations Cup semi-final marked the return of Foé to the Stade Gerland after a loan spell at Manchester City.

In the stands was his family, including his wife, Marie Louise. They had met as teenagers and she had gone to every Canon home game, developing a keen understanding of the game. A day before the Colombia game, Marie Louise had a regular phone call with her husband. “He told me that he wasn’t feeling too well,” she said. “He had some stomach problems and was tired.

“He told me he may not play but asked me not to tell anyone. He asked me to come with the rest of the family and behave as if there was no issue.”

During the game, those concerns were heightened. “Marco told me he wasn’t feeling very well,” Djemba-Djemba told the French TV programme Le Vestiaire. “He was feeling very tired.

“Our keeper Carlos [Kameni] was about to take a goal-kick so I told Marco that once play halts, we’d ask the coach to substitute him. Carlos strikes the ball, it goes past us and I see Marco and Mario Yepes, who was my teammate at Nantes back then, engage in an air duel and Yepes wins the ball, and play continues.

“A few seconds later, I hear Yepes call out and when I look back, Marco was there on the turf, breathing heavily and he was rushed off the pitch. I just told myself maybe he was tired and I knew he’d be ok. We continued playing and no one ever imagined what could happen.”

Marie Louise knew something was badly amiss. “I was watching his every move during the first half,” she said. “He put his hands on his waist which was something he only did when he was tired. He did that a second time and I realised there was something wrong and I knew at the end of the first half he would be substituted.”

She had been surprised her husband had started the game. He had sat out the previous match, against the USA, after gastric problems.

Cameroon’s coach Winfried Schäfer had his concerns over letting the Indomitable Lions midfield maestro continue and had considered taking him off minutes before he collapsed. “Marco had been slowing down and both myself and the team doctor thought he seemed to have run out of energy,” the German told the Guardian a few days after Foé’s death. “Marco refused to come off. He said he felt okay and he wanted to stay on the pitch to make sure we got to the final.”

On 23 June 2020, as the early morning fog that often clouds the hills was pierced by the sun, Cameroon’s capital Yaoundé woke up to its usual hustle and bustle. Around the headquarters of the Ministry of Finance, numerous people clustered around a kiosk perusing the major newspapers.

With coronavirus still a novelty in Cameroon, these people, most of them wearing masks, sought to understand the health situation. Two days earlier, the country’s health minister had announced that 12,592 people had tested positive for the virus with 313 deaths and had urged preventative measures to be respected.

It was 17 years since the death of Cameroon’s number 17. A few papers had dedicated an article to Foé while Cameroon’s national radio had aired, at around 5 am, a 10-minute piece paying homage. Every June 23 rekindles bitter memories for the older generation of fans but for many the healing has been done.

Memories of Foé have largely been eroded, but not for his family. Around midday that day in the Essos neighbourhood, heaps of sand and gravel were poured in front of a four-storey building, barring the way to the main entrance. Two welders had placed iron gates on all the entrances before reinforcing them with huge padlocks to further deter anyone from going in.

Some of the occupants of the building watched confused, with one particularly apoplectic individual screaming at a welder, “What are you doing you idiot? Take that off. I want to get into my office!” Leaning on one of the outer pillars supporting the structure, was a dejected-looking woman in her 40s.

The lady, Marie Louise Foé, has been in a tempestuous legal tussle with her in- laws over the management of property left behind by her former husband. She said her father-in-law Amougou Foé had prevented her from running the assets left behind by her ex-husband.

“I’m here to fight for the rights of my children,” she said. “They had a father who worked hard and invested to take care of their future needs, but my in-laws wouldn’t let me manage the properties of my husband. I have a decision from Cameroon’s Supreme Court paving the way for my kids to benefit from their father’s investment and I’m here to make sure this verdict is respected.”

An elderly woman in her mid-60s, quite mystified by the scene, clapped her hands in the air before screaming Zamba in the local Ewondo language: it means “God”.

“Football killed Foé the first time and now his family is killing him a second time with all these troubles,” the woman fumed, before vigorously clapping her hands again in a gesture of disapproval at what was unfolding before her eyes.

Foé was known for his calm and generosity, but life after him his turbulent. Marie Louise looked disappointed, wearied by life’s struggles and having to raise three kids without their father. The events of the last few years have taken their toll.

In 2018, her eldest son Marc Scott Foé, then aged 22, was sentenced to a five-year jail term in Lyon after being found guilty of armed robbery and sequestration of a priest called Father Luc Biquez.

Foé’s lawyer Alexandre Plantevin argued that his client’s life had been disrupted by the death of his father, which had provoked psychological abnormalities.

Back in Cameroon, what was meant to be a sporting jewel erected by Foé in the Biteng neighbourhood of Yaoundé now rots, home to rodents and snakes. Promises made to Foé’s family by Cameroonian officials still haven’t materialised close to two decades after his death.

A life of promise has yielded to despair.

Njie Enow Ebai is head of sports at Cameroon’s state broadcaster CRTV. He has also written for BBC Sport, the Guardian, New Frame and the Continent and has appeared on Sky Sports, PlanetSports and Supersport. He’s also a writer and editor for the International Basketball Federation FIBA. @NjieEnow