Euro 2020 was a surprisingly bright tournament that, for good and ill, celebrated a returning normality

This piece was written by Jonathan Wilson for issue 42

At Finchley Road, the Tube doors opened. I shuffled to the side, leaning against the Perspex screen at the end of the seats. A man in his early twenties in an England shirt got on in a waft of alcohol fumes and walked straight into me, apologising vaguely as he stumbled across the carriage. That was about 3.30 in the afternoon, and he was already blind drunk.

He was not alone. The whole journey to Wembley for the final had stunk of booze. Everywhere, zombified figures had staggered about, half-chanting half-remembered songs. I’d been having lunch with a couple of other journalists just off Marylebone High Street when the first images emerged of the carnage of Leicester Square. We considered heading over there, but reasoned that was already being covered and it would be better to head straight up to Wembley.

Five hours before kick off, Wembley Way was already carpeted with broken glass and apparently lawless. People danced on kiosks. There was a lot of nudity. Cocaine was openly snorted. There was no sign of stewarding or policing. Trying to force your way through the crowd you had to keep looking up to make sure you weren’t hit by a missile – a bottle, a can or a traffic cone – lobbed pointlessly into the air.

The crush was worst by the box park, where a sheepish David Seaman stood chuckling on the balcony.

A couple of hours later, that mass on Wembley Way would charge the barriers. Volunteers and stewards on minimum wage offered understandably little resistance. There were reports of turnstile operators taking bribes or being threatened into admitting people without tickets. Some just barged in behind others who did have tickets. It’s just as well Covid restrictions meant there were 20,000 empty seats at Wembley or the consequences could have been tragic.

They were bad enough as they were. Fans pleaded journalists in the west press box to tell their stories: how they’d paid hundreds of pounds for tickets only to find their seat occupied and stewards unwilling to move the interloper. Fights broke out between those with tickets and those without.

At around 6.30, a group of 30-40 young men, huddled tight together, rushed past stewards into the seats below the west press box, looking anxiously about them. They very obviously did not have tickets – and that section of the ground was reserved for players’ families and agents. Harry Maguire’s dad suffered bruised ribs. Roberto Mancini’s son ended up having to sit on the steps. This was a dangerous and enormously embarrassing failure of security.

And there had been a warning. The same thing had happened on a smaller scale at the Denmark semi-final. Perhaps the knowledge of the empty seats acted as a lure. Perhaps it was uncontrollable excitement at England’s progress, coupled with the abandon of the lifting of Covid restrictions. Perhaps the nature of Wembley, surrounded as it now is by apartment blocks, offices and hotels, makes the imposition of the ‘ring of steel’ familiar at other stadiums at other big games, impossible. But what it meant was that a tournament that had been largely joyous and optimistic ended amid acrimony and discord and with, for England, a sense not of achievement but of shame.

And at that point it is perhaps worth pausing and asking exactly what that means. For this was not a failure from the team. Despite the sense of disappointment and the vacuous panaceas offered by various pundits in the immediate aftermath of the penalty shoot-out defeat, this was England’s second-best performance in a major tournament. They were behind across the whole month for only nine minutes. Had Marcus Rashford’s penalty gone four inches to the right, England probably would have won. There are questions to be asked and lessons to be learned, but fundamentally this was a success: England have only ever (penalties included) won 14 knockout games at major tournaments; Southgate is responsible for five of them.

Yet the tendency ids to talk of what England “must do” if they are to go one stage further. But that is preposterous. These things are not categorical. Everything is contingent: on the coach, on the players, on the environment and, perhaps most crucially of all, on the opposition. No team should ever go into a tournament thinking that they have failed if they do not reach the semi-final, or succeeded if they reach the quarters. Knockout competitions are about playing well, or at least to a plan, and seeing where that takes you. Sometimes you’re just unlucky or come up against another good team playing well. Which is why Denmark of 1986 (last-16 exit) are remembered more fondly than, say, the Paraguay of 2010 (quarter-final exit).

But then there is the issue of playing well, and what that means. The public and media reaction during the group stage suggested very few thought England were playing well. But, for the first time since 1966, they didn’t concede a goal in the group stage. They scored only two, and looked uninspired and occasionally shaky against Scotland, but they ended up topping the group relatively easily. As Alf Ramsey would happily have pointed out, groups are for getting through: playing well doesn’t really matter if it involves battering lesser sides but then failing in the knockouts. Could Southgate have been more attacking in the group stage? Possibly. Would that have been in any way beneficial in extra-time against Italy in the final? Probably not.

That’s not to say Southgate, or any coach who has led a side to a final, should be beyond reproach. There is a developing belief that he struggles to smell the game; against both Croatia in 2018 and Italy in 2021, he seemed slow to react to a game going against him (then again, in the World Cup qualifier against Poland in March 2021 he seemed slow to react but the players in whom he had faith won the game anyway).

In the longer term, though, there is one other troubling indicator. As systems of pressing have become more and more sophisticated and time on the training ground has become more and more important, so the gulf between elite club and international football has become greater – to the point that it’s not even really the case of the club game leading and the international game following a few years later any more; rather they are distinct forms of the same game, as different in feel and approach as Test and ODI cricket.

The sense had grown that the way to achieve success in international tournaments was to defend deep and hope quality in forward areas took advantage of a moment to pinch a goal. That was how Portugal won the Euros in 2016 and the Nations League in 2019, and how France won the World Cup in 2018 (the 4-3 win over Argentina and the 4-2 against Croatia were the result of the system glitching and them having to make up for either a moment of brilliance from an opponent or a defensive error, and in those spells they offered glimpses of just what a great team that could have been). Southgate, as assiduous in his research as any England coach has ever been, has repeatedly acknowledged that he took France and Portugal as his models.

But the problem with basing a system on researching the past is that it can lead to coaches always fighting the last battle. And in Spain and, more particularly, Italy there is some evidence that international football is beginning to move in a more proactive direction.

It was Italy who kicked off the tournament, against Turkey in front of 12,000 fans in Rome. At that point it was still a novelty to hear a crowd, and there was a welcome sense of familiarity about the whistling whenever Turkey had the ball. Turkey, with an apparently solid central defensive pairing of Merih Demiral and Çağlar Söyüncü, an in-form centre-forward in Burak Yılmaz and a fleet of talented young midfielders, had been widely tipped as dark horses, with the expectation that they would play progressive football under Şenol Güneş, but they were timid and tentative, allowing Italy to generate sustained pressure that eventually yielded three second-half goals.

Italy were just impressive against Switzerland and, despite a much-changed team, against Wales, playing a crisp, proactive 4-3-3 in which the left-wing- back, Leonardo Spinazzola, was extremely attacking, linking well with Lorenzo Insigne as he drifted infield. Turkey remained just as disappointing. Wales missed a number of chances, including a penalty, in beating them 2-0, and when the chance came in the final game, against Switzerland, to salvage a third-place finish, and they at last pressed a little higher, they were picked off on the break, beaten 3-1 to finish bottom of the group with a goal-difference of -7, just one goal better than the record low set by Ireland in 2012.

The mood of carnival initiated on that first Friday was soon extinguished, as Christian Eriksen collapsed on the pitch at Parken having suffered a cardiac arrest. For a tournament that had felt it was offering a reminder that life goes on, that some semblance of normality was returning to a Covid-blighted world, it was a brutal reminder that tragedy had lurked even before the pandemic.

What was most horrifying, perhaps, was the banality of the incident. It had felt like a very familiar occasion, a largely uneventful group game between a debutant and an old-hand fancied by many to reach the quarter-finals. Denmark probed a bit, Finland held them off. Nothing much was happening. And then, quite abruptly, a cheery sunny afternoon was transformed into one of horror. It was obvious from the way players from both sides beckoned the medics on to the pitch that they feared something was badly wrong. The camera, understandably, closed in and Eriksen could be seen, face down on the grass, eyes rolling back. Instantly the thought occurred, “Is he dead?”, and was repelled by the feeling that he couldn’t be, that things like that simply didn’t happen. But as Eriksen, surrounded by protective teammates, received CPR, the cold realisation dawned that he might be, and the memory went back to previous similar incidents, to Fabrice Muamba’s collapse and recovery in an FA Cup tie in 2012, to Marc-Vivien Foé’s death in a Confederations Cup semi-final in 2003.

Slowly news began to filter through. A photographer had seen him raise a hand as he was carried away on a stretcher. He’d spoken to a doctor. Fragments, details everybody wanted to be true, and then, mercifully, confirmed. He’d been taken to Rigshospital, just five minutes’ drive on the other side of the park to the stadium, and he was in a stable condition.

“I didn’t see it myself but it was pretty clear that he was unconscious,” said the national team doctor Morten Boesen, a former badminton star who, with his brother Anders, was the first to try to help him. “When I got to him he was on his side. He was breathing and I could feel his pulse but suddenly that changed and, as everyone saw, we started giving him CPR. Help came really, really fast from the medical team and the rest of the staff and with their cooperation we did what we had to do. We managed to get Christian back. He spoke to me before he was taken to the hospital for more analysis.”

By chance Jens Kleinfeld, a German doctor, was in the stands, having conducted a course in emergency first aid with the sideline medical team earlier in the day. When he saw how serious the situation was, he came onto the pitch. “We gave him electric shocks and continued with the heart massage,” he said. “When you start a resuscitation you need to do it as quickly as possible. But the team doctors are mainly treating many other injuries, which is why it’s more difficult for them to immediately recognise sudden cardiac death. That was clear to me when I saw them trying to pull his tongue out of his throat. That’s not how you save a life. A minimal overflexion of the head is completely sufficient.”

A defibrillator was used within two or three minutes of Eriksen losing consciousness, which gave him a high chance of recovery. “He opened his eyes and spoke to me,” Kleinfeld went on. “I asked him, in English, ‘Are you back again?’ He said, ‘Yes, I am here.’ And then he said, ‘Oh shit, I’ve only just turned 29 years old.’”

Almost unbelievably, the game resumed an hour and three-quarters later. Kasper Hjulmand, the Denmark coach, said he had effectively been given two options by Uefa: either to finish the game that night or to return at noon the following day. “We knew we had two options,” he said. “The players couldn’t imagine not being able to sleep tonight and then having to get on the bus and come in again tomorrow. Honestly it was best to get it over with.”

Although he insisted Uefa had not applied any pressure to play, he also acknowledged his players were in not fit state to do so. “There are players in there who are completely emotionally finished … they are holding each other,” he said. “It was a traumatic experience. I said that, no matter what, everything was OK. We had to allow ourselves to show joy and aggression, to make room for the emotions. You cannot play a football match at this level without being aggressive.”

Simon Kjær, Denmark’s captain, was unable to carry on, substituted soon after the restart. He had helped put Eriksen in the recovery position and then, with Kasper Schmeichel, had comforted Eriksen’s wife on the pitch. “Simon was deeply, deeply affected,” said Hjulmand. “Deeply affected. He was in doubt whether he could continue and gave it a shot, but it could not be done.”

As it turned out, Denmark lost the game 1-0, Joel Pohjanpalo heading in Jere Uronen’s left-wing cross and Pierre-Emile Højbjerg tamely missing a penalty. For Finland, a win in their first tournament game should have been a cause for celebration; as it was, their fans were muted, and their main memory of that day was probably the poignant call and response they engaged in with Denmark fans during the suspension in play, one side of the ground shouting, “Christian” and the other replying “Eriksen”.

The atmosphere for Denmark’s second match, against Belgium, was predictably passionate, but although they took an early lead through Yussuf Poulsen, the brilliance of Kevin De Bruyne, who came off the bench at half-time as he continued his recovery from a fractured cheekbone and eye- socket sustained in the Champions League final, turned the game. The Danes, though, did achieve a cathartic victory in their final game, thrashing a sluggish Russia 4-1 to take second place in the group behind Belgium.

Briefly, it seemed the pre-tournament pessimism about the Netherlands might be misplaced. Euro 2020 was their first tournament since coming third at the World Cup in 2014, but there had been clear signs of progress under Ronald Koeman, built largely around the fine generation of Ajax talent that reached the semi-final of the Champions League in 2019. That momentum, though, was checked when Koeman accepted the Barcelona job to be replaced by Frank De Boer, a manager whose early success at Ajax had not been matched by subsequent stints at Inter, Crystal Palace and Atlanta United.

As ever when doubts set in around the Netherlands – and often when they don’t – debate turned to tactics. Was De Boer attacking enough? Was his use of the back three (which Louis van Gaal had employed in 2014 and Koeman at times after that) somehow contrary to Dutch tradition?

A patchy 3-2 win over Ukraine – an odd match that comprised a tight first half, Dutch dominance for 25 minutes, Ukrainian dominance for 10 minutes and then a final Dutch surge that brought the winner – and comfortable victories over Austria and North Macedonia meant the Netherlands went through as top-scorers in the group stage, with Denzil Dumfries widely praised for his sallies forward on the right, but there was still a sense of fragility about them, and that was exposed in the last 16.

The Netherlands were controlling possession without looking overly threatening against the Czech Republic when Matthijs de Ligt was sent off for a cynical handball, at which the Dutch capitulated and conceded twice. Attempts to blame the red card as though it were some random act of god made little sense – and besides, it was hard to imagine the Czechs collapsing in the same way had they had a man sent off. De Boer resigned soon after.

North Macedonia lost every game, but the way they embraced their inclusion justified the use of the Nations League to determine the eight sides who should contest the four play-off spots. The problem with traditional qualifying is that a smaller nation can be burdened by poor historical performances for years: a low coefficient means a difficult draw and so an emerging young generation may have to wait three or four cycles slowly improving its coefficient before having even a realistic opportunity to qualify. A minnow delighted to be at the Euros, playing sprightly and engaging football adds far more to the tournament than yet another middle-ranker wearily plodding through the motions, seeking not to be humiliated and hoping to scrape enough to make the last 16.

And they had their moment. Goran Pandev’s equaliser in the 3-1 defeat to Austria may have been the result comical defending and goalkeeping, but a country’s first goal in major tournament history is always a landmark, and it was scored by absolutely the right player, a 37 year old who had made his international debut 20 years previously.

England’s build-up, disrupted on the pitch as it was by the absence of players who had been involved in the Champions League and Europa League finals and by injuries to Harry Maguire and Jordan Henderson, revolved around events off it, particularly the booing by a section of fans of their taking of the knee. As Boris Johnson and Priti Patel pointedly refused to condemn those booing – although she would later deny it, the home secretary explicitly criticised the players, saying, “I just don’t support people participating in that type of gesture politics” – and other populists made specious links to Black Lives Matter and Marxism, the players and Gareth Southgate stood firm and it turned out they had public support. The booing was very audible in the first pre-tournament friendly, against Austria, was met by applause in the second pre-tournament friendly, against Romania, and then was almost instantly drowned out before England’s tournament opener, against Croatia. By the final, when both England’s and Italy’s players took the knee, the booing had become a non-event.

It’s far too early to say how significant a fact that is. There is always a tendency to see wider significance in tournaments, which have, at best, symbolic importance. Perhaps West Germany’s success in the 1954 World Cup was an important emblem of the country’s reacceptance into global society after the War, but the German economic miracle would have happened anyway. Great claims were made for the victories of France at the 1998 World Cup and South Africa at the Cup of Nations in 1996 as examples of racial harmony, and perhaps in the context of the time they did offer a symbol of hope, but two decades on, it would be hard to argue either was representative of lasting change.

But still, when Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho and Bukayo Saka were racially abused on Twitter after missing their penalties in the final, it was striking how unanimous the condemnation was – and striking also that there were ‘only’ around 1000 Tweets, roughly 70% of which originated from abroad; 300 abusive Tweets are repulsive enough, those responsible should be prosecuted, and Twitter itself should be better at preventing such outrages, but they do not represent some mass upsurge of English racism. It seemed telling as well how many were prepared to make the link between that abuse and the populist culture-war rabble-rousing of Johnson and Patel, none more pointedly than Tyrone Mings. There was the usual fatuous bleating from right-wing columnists, but the panicked government backtracking suggested where it feels the mood of the country is going.

England’s line-up for the opener drew less consequential grumbling from those who believed fielding Declan Rice and Kalvin Phillips together at the back of midfield was overly negative, something that highlighted how the media/public environment so often works against the England team. This, after all, was a game against Croatia, who had beaten England in a World Cup semi-final three years earlier. But even leaving aside the opposition beyond that, the attitude suggested the weird failure to recognise that group games are about getting through and about preparing for later. International teams have little enough chance to play together: why would any side reject the opportunity to practise a system it believes it may need later on? What good would come of, say, winning 4-0 rather than 1-0?

More eye-catching, though, was the use of Kieran Trippier at left-back, a canny defensive move that stymied Croatia’s right flank and suggested Southgate’s pleasing willingness to make minor tweaks according to the opposition; not for him hackneyed motions of not changing a winning team or just picking your best XI and hoping they can sort it out (and how weird it now seems that just 15 years ago, England were paying Sven- Göran Eriksson a fortune to do just that).

After a promising start, England fell away towards the end of the first half but an excellent team move converted by Raheem Sterling brought a 1-0 win. The reaction was tellingly split: on the one had there were those who moaned about (or mocked) a less than eventful 1-0 victory over ageing and slow opponents, and on the other there were those who exulted in a controlled midfield performance that had successfully held Croatia at arm’s length. Neither was wrong, as such, but it did suggest just how polarising the England team is; had that been a top-four side winning a club game it would have been talked about as a comfortable if uninspiring win against limited opponents, the sort of match that happens regularly in a successful season. But with England the reactions are always extreme.

They were even more extreme after the second game, against Scotland. After all the excitement about their first qualification for a major tournament in 23 years, the Scots had begun in the traditional manner, which is to say anticlimactically. They didn’t play badly against the Czech Republic, but were undone by two goals from Patrik Schick, the second of them a preposterous shot from the centre-circle.

Scottish fans came to London in their thousands and they went home happy enough with a 0-0 draw. Again the reaction was hugely exaggerated on both sides. England did not play well, Scotland had a couple of decent chances and claimed the moral victory, but as it turned out results in other groups meant that the point was enough to secure England’s qualification.

Scotland, meanwhile, had to beat Croatia to go through: they did not, and never came close, undone by a first- time outside-of-the-boot shot from Luka Modrić as they lost 3-1. England, giving Jack Grealish his only start of the competition in the absence of Mason Mount, self-isolating after a protracted post-match conversation with Scotland’s Billy Gilmour who subsequently tested positive for Covid, beat the Czechs comfortably enough, 1-0. Again they began well before fading. The second half was effectively a non-event, although whether that was because they had successfully shut the Czechs down or because both sides, knowing they were through, were happy enough to ease off was unclear.

Group E felt almost like a work of parody, so determinedly did each of the four sides play to stereotype. Slovakia were grindingly awful, playing a weird blockish 4-4-2 with two false nines and nobody capable of running beyond them, yet they somehow beat Poland in their first game, thanks to a sudden burst of brilliance from Róbert Mak, darting in from the left before scoring via the post and Wojciech Szczęsny and then a needless lunge from Grzegorz Krychowiak that earned him a red card.

Sweden sat deep in a 4-4-2, but at least had the threat of Alexander Isak up front and Emil Forsberg coming off the left. They had just 15% possession against Spain, yet still forced a 0-0 draw. Luiz Enrique had spoken of adding greater verticality to his side, but ingrained habits are often hard for national sides to break.

It was a similar story for Spain against Poland, Álvaro Morata’s first-half goal cancelled out by Robert Lewandowski as Gerard Moreno missed a penalty. Morata had a strange tournament, clearly vital if Luis Enrique wanted his side to get the ball forward quickly, but suffering one of his familiar crises of confidence in front of goal, which led to him and his family being subjected to abuse on social media. A Forsberg penalty saw Sweden past Slovakia in a dismal game.

But that did set up a thrilling finale to the group, as Spain, despite missing another penalty, thrashed Slovakia while Sweden beat Poland 3-2, a late fightback not enough to rescue Paulo Sousa’s side. Poland were hampered by injuries to Arkadiusz Milik and Krzysztof Piątek, but the pattern was very familiar: the expectations generated by the presence of Lewandowski nowhere near lived up to.

As it turned out, that dramatic finale to Group E was only the prelude to an even more extraordinary evening. At various points, Portugal occupied all four places in the table as they ended up drawing 2-2 with France, while Germany needed a late goal from Leon Goretzka to avoid going out after twice going behind at home against Hungary.

For Germany the problems were all too familiar. Defensively they were hopeless, while going forward they had no clear pattern of attack despite their abundance of gifted players. Jogi Löw had switched to a 3-4-3 just before the tournament, seemingly in a bid to overcome his lack of full-backs. Although it worked against Portugal, who seemed bewildered by Germany’s regular switches of play, Germany were toothless against France and rudderless against Hungary, sneaking their equaliser through desperation and weight of attacking numbers against a team unable quite to believe what it was about to achieve rather than anything resembling a coherent plan.

Portugal, as it turned out, weren’t much better. They laboured against Hungary before a deflected pass led to a deflected goal that broke the deadlock with six minutes to go. A narrow defence was exposed by Germany and although they arguably had the better of their draw with France, they still seemed dully mechanical, over-reliant on the goals of Cristiano Ronaldo. And even France, it turned out, weren’t what they might have been.

Which left Hungary, who before the tournament would have been more than happy with two points from the group of death, but probably ended up disappointed not to have gone through. They were well-organised at the back and adept on the break, good enough that it can now be said that, for all his many other failings, and whatever the cost in tax breaks, Victor Orbán has achieved his goal of elevating the standard of the Hungarian game.

The new Puskás Aréna in Budapest is the centre-piece of that and was the first stadium in the tournament to be full to capacity as Hungary relaxed its Covid regulations at the end of May, using the fact that it had hit a total of 5million vaccinations (of a population of 9.8million) as justification. Given deaths were down to eight a day by that point, perhaps that was reason enough – although Hungary also had the second- highest death rate in the world (behind only Peru) – but the stadium had been built for the Euros and it would have been an enormous anti-climax for Orbán had games there been played behind closed doors.

His attempt to regenerate Hungarian sport, after all, is as much about making Budapest a regular host as about winning medals. In recent years, Hungary has staged judo, wrestling and aquatics world championships. In 2020, the Puskás Arena stepped in to stage the Uefa Super Cup when the pandemic forced a rejig of the schedule while both legs of the Champions League last-16 ties between Manchester City and Borussia Mönchengladbach and Liverpool and RB Leipzig were held there in February and March when Covid restrictions made playing the games in the UK and Germany impossible.

After months of watching games being played in empty or half-empty stadiums, there was something undeniably thrilling about the passionate full houses in Budapest. But the more concerning aspects should not be ignored. Firstly, those who called for Budapest to be awarded hosting rights to the semi-final and final ignored the fact that Budapest wasn’t necessarily safer than anywhere else; the Hungarian government had simply chosen to abandon restrictions.

Then there was the presence behind one goal of a large group of fans in black T-shirts. These were part of the Carpathian Brigade, an overtly racist and homophobic nationalist group. During the first week of the tournament, the Hungarian government had passed legislation banning the “promotion” of LGBTQ “lifestyles” in any material intended for under-18s, a move in very obvious violation of Section 7 of Article 7 of Uefa’s Statutes: “Member Associations shall implement an effective policy aimed at eradicating racism and any other forms of discrimination from football and apply a regulatory framework providing that any such behaviour is strictly sanctioned, including, in particular, by means of serious suspensions for players and officials, as well as partial and full stadium closures if supporters engage in racist behaviour.”

When Uefa banned the Munich authorities from lighting the Allianz Arena in rainbow colours for Germany’s match against Hungary (having decided no action should be taken against Manuel Neuer for wearing a captain’s armband in rainbow colours) it was an acknowledgement that its regulations outlawing all political symbols (which are broadly speaking sensible; Uefa cannot regularly be arbitrating on which symbols are and are not offensive or provocative) outweigh its commitment to tackling discrimination. There were also reports of local authorities in both Hungary and Azerbaijan confiscating rainbow flags. While Uefa cannot reasonably be expected to control the actions of local security, that does raise the very obvious question of why, if it really is committed to diversity, it allows discriminatory countries to host major events. Fifa, almost certainly, will be facing similar questions in Qatar in 2022.

Perhaps all that matters is the spectacle. The final day of the group stage produced several hours of exhaustingly thrilling football. After all the concerns Euro 2020 might be blighted by the weariness that had spoiled the 2002 World Cup, it was open and fun, far more watchable than the grim slog of Euro 2016. Yet that doesn’t mean the format is the right one. Playing 36 games to eliminate eight teams, 71% of the tournament to lose 33% of the competing nations, is a lot. This time it worked, but there is a serious risk of dead rubbers.

More significantly, the entire notion of best third-place teams is unfair. Teams who get a hard draw are doubly disadvantaged. As soon as groups cease to be discrete integrity is lost. In Group D, for instance, England and the Czech Republic both knew they were already through before playing their final game, which would not have been the case had they been in Group A or B. Wales, Finland and North Macedonia all had the advantage of playing teams that had won their first two games and rested players. That’s an unfortunate but inevitable consequence of any group system, but at least when groups are self-contained, there is a sense that the other two teams in the group are in part responsible for giving a rival an advantage. But, really, why should teams in other groups be affected by that?

Uefa are understood to be concerned by the issue, and the likelihood is that by 2028 the Euros will have expanded to comprise 32 teams. A 16-team format is probably still preferable, in that it concentrates quality, but football is not cricket: tournaments never get smaller. And while expansion will inevitably mean dilution, the likes of Norway, Serbia and Ireland are objectively no weaker than, say, Finland, Slovakia and North Macedonia.

Expansion, though, does mean that the list of potential single-country hosts is reduced, probably to just England (perhaps with added Cardiff, Glasgow and Dublin), Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Russia and maybe Turkey. The multi-host format used at Euro 2020 did not work: the advantage of being a host is magnified when other sides are shuttling from Seville to St Petersburg to London, or Amsterdam to Baku to London. Covid regulations meant very few fans could travel, but it’s clearly absurd for hordes of supporters to be taking four or five long flights across a continent even before the environmental cost is taken into account.

But multiple hosts can work so long as logistics are the prime consideration. There is no reason why the eight groups could not be divided between four paired locations (eg London-Manchester; Lisbon-Porto; Vienna-Budapest; Moscow-St Petersburg), with group winners staying where they are for their last-16 game, and everybody decamping to, say, Amsterdam-Rotterdam for the quarter-finals onwards.

The final games in Groups E and F were the beginning if the tournament’s golden phase. The first day of the last 16 was perhaps anti-climactic by comparison with what was to follow, but Denmark’s 4-0 win over Wales confirmed what a tactically astute side they are, with Andreas Christensen shifting into midfield to deny Aaron Ramsey space. Italy, then, were severely tested by an Austria side producing probably their best tournament performance in more than four decades before a Federico Chiesa goal turned the game their way.

The Dutch collapse against the Czechs the next day was followed by the elimination of the defending champions, Portugal beaten 1-0 by Belgium. Belgium’s ageing back three had been a major concern for Roberto Martínez with their lack of pace leaving them vulnerable to counter-attacks. He solved that by having them sit deep and play on the break to Romelu Lukaku. Portugal, suddenly forced to take the game to their opponents, struggled and, when an incursion by Lukaku created space just before half-time, Thorgan Hazard lashed in what turned out to be the winner from 25 yards. Portugal face serious questions: how do they get the best out of their fleet of creative midfielders while still incorporating the goal-scoring threat of Cristiano Ronaldo? And is Fernando Santos’s instinctive caution really the best way to utilise this crop of players (especially when that defence is so susceptible in wide areas)?

And then came the two astonishing matches that, in terms of goals and drama, meant probably the greatest single-day of knockout football in the same competition since the FA Cup semi-finals of 1990. First, Spain’s astonishing battle with themselves and occasionally Croatia: giving up a laughable own goal, surging into a 3-1 lead and then panicking in the final 10 minutes as soon as Croatia started lofting the ball into the box. Only a super Unai Simón save, making up from his earlier doziness in dealing with a simple backpass, kept the scores level, before Álvaro Morata lashed in a brilliant goal to tip the game back Spain’s way.

How to follow a 5-3? With an even better game. France, with both left-backs injured, began in an uncomfortable 3-4-3 with Adrien Rabiot at left-back. Switzerland dominated, sharper in midfield and seemingly able to get their wing-backs into crossing areas at will. Steven Zuber, in particular, caused problems, setting up an opening goal for Haris Seferovic. A switch to a back four, still with Rabiot at left-back, gave France better balance, but when Benjamin Pavard took down Zuber in the box six minutes into the second half, Ricardo Rodríguez had the opportunity to put the Swiss two up. He did not take it, Hugo Lloris saving a nervy penalty low to his right.

Within a couple of minutes, France were level, Karim Benzema’s stunning touch, dragging the ball from behind him, allowing him to score his third of the tournament. His fourth followed two minutes later and, when Paul Pogba slammed in a brilliant strike with quarter of an hour to go, it seemed that Switzerland would be left regretting that two minutes when a possible 2-0 became 1-1. Certainly Pogba’s extended celebration suggested he thought the game was done. But Seferovic headed his second and then, in the final minute, Pogba lost possession cheaply and Granit Xhaka laid in Mario Gavranović to level. Although Kingsley Coman then hit the bar, the outcome of the penalty shoot- out felt weirdly inevitable. In the end it was Kylian Mbappé, looking anxious and rushing his kick, whose effort was saved.

No nation does football meltdown as well as France, and afterwards it emerged that there had been a row in the stands between Rabiot’s mother and the families of Pogba and Mbappé. Rabiot did not have a good game, but it was the failure of Mbappé and Pogba that felt emblematic of France’s struggles.

They have wonderful players and have incredible depth, but this France has always been oddly unlovable, as though Didier Deschamps were determined to fashion a side in his own cussed image. In the 20 minutes from Rodríguez missing the penalty to Pogba’s goal, France showed what they could be.

Yet Deschamps had insisted on a more grizzled approach, the result of which seemed to be that France came to believe their own myth, that they didn’t have to play well because they had enough great individuals to bail them out.

Pogba’s performance felt like his career in microcosm. He is a sublimely gifted player, with a great range of passing and a ferocious and accurate shot, but he lacks the discipline to operate as a holding midfielder and isn’t quite good enough with his back to goal to play as an attacking midfielder. 30 years ago he would have been a great box-to-box player but unless he can find a means of concentrating for 90 minutes he is flawed as a holding midfielder in the modern game – and it was remarkable to see Patrick Vieira, Roy Keane and Graeme Souness, three greats of the position, united in their criticism of his sloppiness. At 28, it feels as though it may be too late for him to establish himself as a true great.

There are worrying signs about Mbappé as well. He is still only 22 and no career is ever without its dips, but he has been at his very best only fleetingly over the past year. The concern must be that the longer he stays at Paris Saint-Germain, playing relatively untesting games in Ligue 1, the greater the danger of stagnation.

When I booked the sleeper back from Glasgow to London, it seemed like a fine plan. If there was no extra-time between Sweden and Ukraine, I would have time even to walk back to Glasgow Central by 2340. But as my editor at the Guardian pointed out, it did have the look of a game that would go to penalties. Still, even then, I could catch the 2316 from Mount Florida and be there with 12 minutes to spare. Or I could get an Uber; there would, after all, only be 11,000 in Hampden.

Of course it went to extra-time. Ukraine, switching to a back three, started off very dangerously, switching play quickly and threatening through Andriy Yarmolenko, although it was Oleksandr Zinchenko, switched to left wing-back, who put them ahead. Sweden levelled through Forsberg just before half-time and had the better of the second half, Forsberg twice hitting the woodwork, as did Serhiy Sydorchuk for Ukraine. Going into extra-time, Sweden seemed by far the likelier winner, but that all changed when Marcus Danielson was sent off as his follow-through clattered into the knee of Artem Besedin. Both sides looked exhausted but in injury-time at the end of extra-time, Artem Dovbik plunged onto a Zinchenko cross to force home a winner.

Highly fancied before the tournament, Ukraine had played well only in patches, their most memorable contribution to that point the controversy over their shirts, which bore in the fabric not only a map of the nation that included Russian-occupied Crimea, but also two slogans on the collar – “Glory to Ukraine!” and “Glory to heroes!” – that had been in currency for more than 120 years, used not only by protestors on the Maidan demonstrating against the Kremlin- backed president Viktor Yanukovych, but also by fascist-aligned nationalist groups during the Second World War. The difficulty of mediating what phrases are acceptable, of course, is why Uefa has a blanket ban on political slogans and imagery. In the end, it decided “Glory to Ukraine!” was acceptable but “Glory to heroes!” was not.

Qualification for the quarter-final, however uncertainly achieved, was a significant milestone for Ukraine and after the dismal exit having lost three out of three group games in France, without scoring a goal, it was clear that there has been progress under Andriy Shevchenko.

As soon as the goal went in, I smashed out a top and a tail – to amend the report I’d already had to file on 90 minutes so the extremities of the country who get the first edition would find out the following morning that the final last-16 tie had gone to extra- time – and raced off to Mount Florida station, hoping I could catch the 2246. I was just about on time, but there was a long queue snaking back and forth and down Bolton Drive. Nobody seemed to know whether trains were running to timetable or whether there was a shuttle service.

A couple of trains trundled in, which seemed to suggest a shuttle, but as the wait got longer, I got uneasy and started trying to order an Uber. Eventually, after multiple cancellations, an Uber reached the bottom of Florida Drive just as another shuttle arrived. I opted for the train, which was bizarrely empty, no more than 50% capacity, and hammered out my Guardian rewrite. Everything seemed fine, until we sat for 10 motionless minutes on a bridge over the Clyde. I made the sleeper by about eight minutes, and, as I wrote my piece for Sports Illustrated, vowed never to take such a stupid risk again.

In Munich, Belgium’s golden generation finally reached its end. Vincent Kompany and Radja Nainggolan had already gone, but with nine outfielders over 30, there will almost certainly be major changes ahead of the World Cup. They simply cannot attempt to get by again with a backline so devoid of pace. Not that Belgium didn’t cause Italy problems in the quarter-final, Gianluigi Donnarumma making a couple of stunning saves, and Lukaku, who had an excellent tournament, agonisingly close to turning in a cross at the back post, his stretching effort deflecting to safety off Spinazzola. First-half goals from Nicolò Barella and Lorenzo Insigne and a determined second-half rearguard saw them through, but they lost Spinazzola, who had been brilliant on the left, to a serious Achilles injury.

Having seen off France, the Swiss could have upset Spain as well and, drawing 1-1, looked the better side when Nico Elvedi was sent off after 79 minutes. This time in the shoot-out their nerve failed them, three misses handing Spain a slightly fortunate victory. Denmark’s wing-backs saw them through against the Czechs, who were reduced in the end to lumping balls aimlessly into the box where the three huge Danish central defenders happily headed them clear. And then came England, sweeping Ukraine aside in Rome with a fine performance in which both Raheem Sterling and Harry Kane excelled.

Spain’s luck ran out in the semi-final, when they played far better than they had against either Croatia or Switzerland. Having fallen behind to a Federico Chiesa goal, they levelled through Morata, on as a substitute, but his redemption tale turned sour in the shoot-out.

Southgate, having contained Germany with a 3-4-3 and then attacked Ukraine with a 4-3-3, stuck with the more aggressive formation against Denmark and for a while, after their habitual bright start, England seemed in danger of being overwhelmed. But having conceded their first goal of the finals to Mikkel Damsgaard – the only direct free-kick scored in the Euros – they responded well, levelled as neat interplay between Kane, Sterling and Bukayo Saka forced an own goal and then won it in extra-time as Kane knocked in the rebound after his weak penalty had been saved.

From the press box at the opposite end of the ground, through a crowd of players, and with no replays, it was impossible to tell whether Sterling had actually been tripped, but from the furore on social media, my assumption was he must have dived egregiously. When I finally saw footage the following day, I was startled there’d been any fuss at all: Sterling’s right knee was clipped by Joakim Mæhle and his left hip was then barged by Mathias Jensen. It’s the sort of decision given in the Premier League without comment every week. Far from being a disgrace, the incident seemed rather to demonstrate the hysteria that surrounds international football, and how many people watch it who are not regular viewers of the game.

And so the final. Southgate, presumably reasoning he would not be able to control midfield against Italy, preferred the 3-4-3. At first the plan seemed to be working, as one wing-back, Kieran Tripper, crossed for the other, Luke Shaw, to open the scoring and for much of the first half England were able to hold Italy at arm’s length with relative comfort.

But England have made a habit over the past quarter century of taking an early lead in knockout games only to falter. They did it against Germany in 1996, against Portugal at 2004, against Brazil in 2002, against Iceland at Euro 2016 and against Croatia in 2018 (even against Colombia in 2018). The explanation used to be that it was because England are technically deficient, that they cannot hold the ball as well as other major sides and so find it difficult to manage games in the way other major nations can. But while that may have been true once, it clearly isn’t any longer (equally, the idea that Premier League hampers England by restricting opportunities for young players looks very strange now. Roughly 30% of players in it are England-qualified, which is to say that every weekend 60-70 English players are starting games in the most diverse and competitive league in the world; that should be enough to find a decent squad. If there is a bottleneck, it is big clubs stockpiling youth talent, which is a problem that extends far beyond England). The issue rather seems mental; when the line gets close, England still have a tendency to tighten up. And when they do that, they drop deeper and deeper and start whacking the ball long.

As the second half went on, Italy’s pressure became increasingly intense. Perhaps, if Jordan Pickford’s save had trickled wide of the post rather than against it, allowing Leonardo Bonucci to ram the rebound over the line, England may have held on, but the sense then was that the equaliser was coming. Southgate’s research-heavy approach, his radical prudence, had eliminated many English vices, but not that one.

An immediate switch to 4-3-3 steadied the ship, but could not avert penalties. There was much wisdom after the event about the decision to bring on Sancho and Rashford late to take penalties (perhaps they could have come on sooner, but how long, really, could England have coped in a loose 4-4-2 with Rashford at right-back, a curious finale for a side that began the tournament with four right-backs in its squad?) and about Saka taking the final kick, but that again perhaps demonstrates the impossibility of England management, how surrounded it is by empty noise. Southgate had studied this for months, worked with players and specialists and psychologists. This wasn’t an ad hoc, “Who fancies it, lads?” This was meticulously planned, and penalties are probably the area of football that yield most readily to study and data analysis. In that, you probably have to trust the experts, unfashionable as that was of thinking may now be.

In a tournament in which there was no outstanding team, Italy deserved their success. They may have needed penalties in the semi and the final, and they may have spent much of the final 20 minutes of their quarter-final against Belgium wasting time, but before the injury to Spinazzola, they produced occasionally exceptional football. And no team that has gone 34 games unbeaten can be considered fortunate. Roberto Mancini’s revamp of the Italy style has been a clear success.

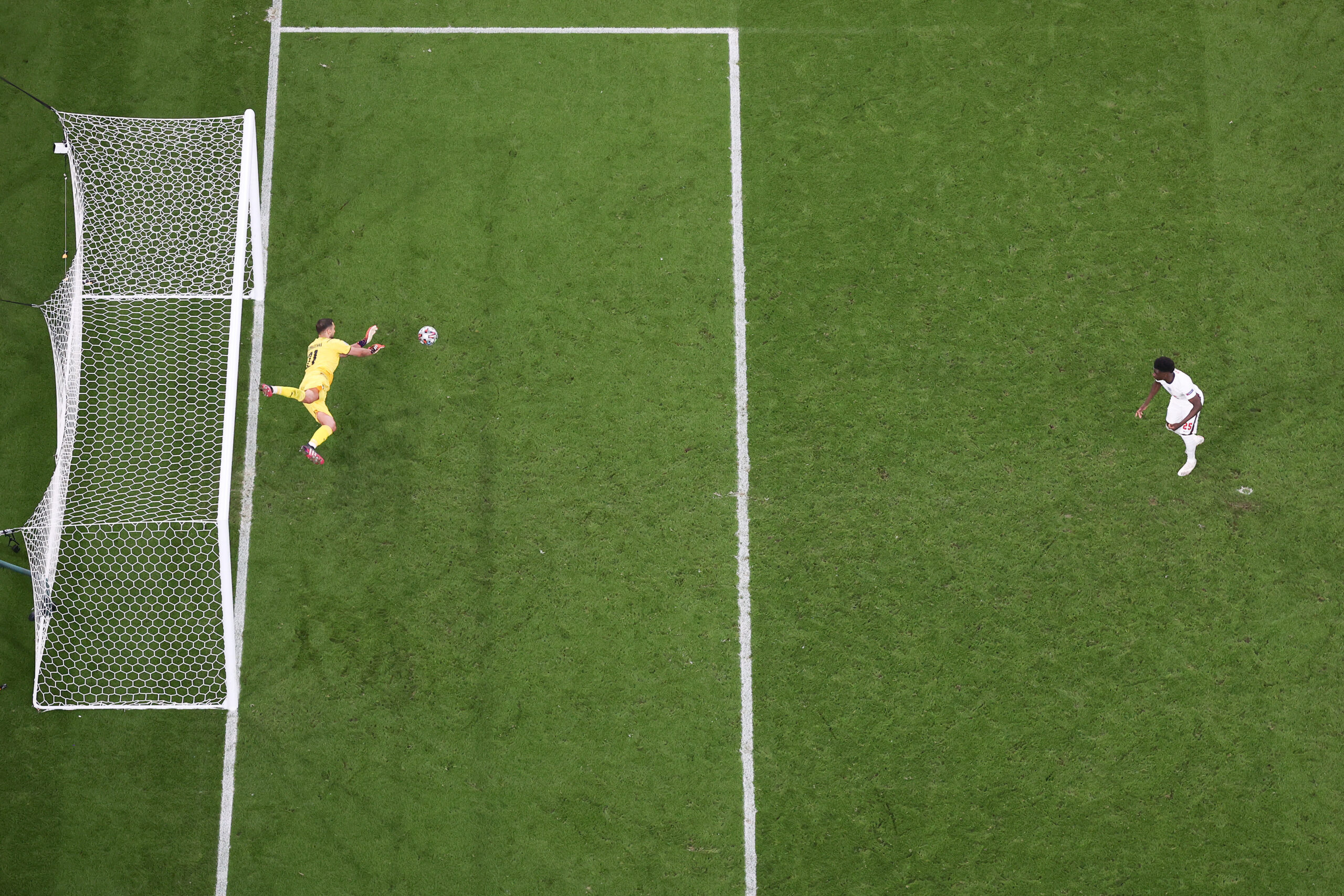

Equally England would have been worthy winners – not especially thrilling perhaps, but then few champions of international tournaments are. The margins in major tournaments are often extremely fine. Had Rashford’s penalty, having sent the keeper the wrong way, been four inches to the right, it would have gone in and England would probably have won.

But then another thought intervenes. Perhaps winning is the only thing that matters. Perhaps those watching at home on television, or on big screens in pubs or box parks across England don’t care. But if England do finally end the 50+ years of hurt, do we really want it to be like that? Amid broken glass and crying children, boorishness and acrimony? And would it not be better to win it with a goal that can be replayed and savoured as often as Geoff’s Hurst’s third against West Germany in 1966, rather than a penalty? And, likeable and admirable as this set of players is, it might be nice to win at a time when, politically, it doesn’t feel like the rest of Europe is desperate for England to fail.

Beyond Italy and England, perhaps, it didn’t much matter who won. What was important was that, a year late, the tournament took place at all. Perhaps it didn’t pay in places to examine the crowds too closely, but that they were there after months of empty stadiums added enormously to the spectacle. And the football was, by and large, enterprising and fun. For the week from the end of the group stage to the end of the last 16, it was spectacular, as thrilling as any major tournament in recent memory.

Perhaps that was despite the format and the circumstances, perhaps players were exhausted, but here was a reminder that sometimes that it is football is enough. The game somehow finds a way to transcend its problems and to grip a continent. It has done so for more than 150 years, though war and famine and plague, and despite all the difficulties of financing and the pandemic, there is no reason to believe it will not continue to do so for several decades at least.

And sometime, perhaps, England might win a tournament again.

Jonathan Wilson writes for the Guardian and Sports Illustrated. His latest book is The Names Heard Long Ago. @jonawils