Champions League quarter-final, second leg, Stamford Bridge, London, 14 April 2009

With the results of four Champions League Quarter Final second legs to be decided in the next two days, revisit a classic of the genre; written by Scott Oliver and published in The Blizzard Issue 45

Six minutes is a long time in football. Six minutes – you may already be aware of this, already have heard on the grapevine – is a particularly resonant period of time for Liverpool in Champions League football. So it was that, for six minutes after the indefatigable Dirk Kuyt had sent a bullet header from a bullet cross by Albert Riera past Petr Čech on a heady spring evening at Stamford Bridge in April 2009 – putting his team 4-3 up on the night but still 6-5 down on aggregate – I dared to dream that Liverpool might pull off one of the all-time great European comebacks and progress to the semis for the fourth time in five years.

The 2009 quarter-final was the apogee of a short-lived yet intense and occasionally bitter rivalry that had arisen suddenly, with few omens in the tea leaves, and was refracted in large part through five consecutive years of Champions League tête-à-têtes. But first the two clubs had to create a mutual history of antipathy, a past to act upon that present and give it its dimensions. The initial impetus – if not quite the catalyst – came in the summer of 2004 with two Iberian arrivals who became Shakespearian rivals: José Mourinho and Rafael Benítez, the hottest coaches in Europe at the time. Yet even this moment needed events to shift into propitious alignment for the elements of a rivalry to coalesce – particularly when the clubs had never really had much reason to get uppity with one another – and such a shift can be traced back just over 12 months to the final game of the 2002- 03 Premier League campaign: Chelsea versus Liverpool at Stamford Bridge, both teams having 18 wins, 10 draws and 9 defeats, shooting out for access to Champions League lucre and lustre.

Chelsea were in financial disarray – the club was set to default on a £75m loan and earlier in the year had borrowed against future TV revenues – and a Russian oligarch in the right place with the right friends during the perestroika privatisation divvy-up was looking to funnel some of his fossil-fuel money through London. Sami Hyypiä and Marcel Desailly exchanged headed goals before Jesper Grønkjær drove in what turned out to be the winner, still in the opening half-hour, while Steven Gerrard was later sent off for a grisly over-the-top tackle on Graeme Le Saux. Chelsea advanced, Liverpool’s supporters magnanimously applauded Gianfranco Zola from the pitch on his last appearance for the Blues, and a few weeks later Roman Abramovich, having entertained notions of buying several clubs and held preliminary talks with Tottenham, settled instead on Chelsea at a price of £140m (in today’s money, about two-thirds of a Neymar). The following year’s European adventure took them all the way to a self-inflicted semi-final defeat to Monaco (who went on to lose the final to you-know-who) and, with that, a juggernaut was up and running: seven appearances in the Champions League’s last four in 11 seasons.

Mourinho’s Champions League victory with Porto had surfed a large dollop of good fortune – notably, the disallowed Paul Scholes strike prior to Mourinho’s famous touchline sprint at Old Trafford, but also in the limp Monaco that contested the final – even as he mythologised the triumph as an inevitable unfolding of his genius, expressed through the organisation imposed on those blue-and-white-clad limbs. The hagiography would brook no contingencies, only predestination. His famous opening press conference at Stamford Bridge contributed enormously to the mythos: a press pack swooning before his considerable charm had subtly if inadvertently misquoted him, depicting him as the definite article when he had in fact said, “I am not one out of the bottle. I think I am a special one”. This might be a Hispanist’s nit-picking, but translating out from the Portuguese, that very naughty boy was not claiming to be the Messiah – although he perhaps felt so, since, he told us, had he stayed in his “beautiful blue chair” in Porto, first would be “God and, after God, me” – so much as saying he wasn’t table wine. Even so, “a special one” quickly solidified into “the Special One”, and who was José ever to divest himself of an Emperor’s clothing.

Benítez had also arrived with some swag in the back pocket – a Uefa Cup victory with Valencia, along with a second La Liga title in three years, a formidable achievement even before TV money had fully embedded the clásico duopoly – and had more in common with Mourinho than shared Iberian provenance and recent success. Both had negligible playing careers, both had sports science degrees, both were meticulous tacticians. There was no initial animosity, no baggage brought through llegadas, and yet, with some revisionism, they came to be depicted as radically different personalities, markedly divergent in the outward expression of their inner worlds’ churnings, inevitably bound to grate against each other. There is some truth to that, of course, but to portray Rafa as a genial teddy bear and Mourinho as a perennially chippy Grinch, a sneer in an Armani suit, is too simplistically binary. Just as José had his wit and charm, so Rafa had his tetchy side. Moreover, it is misleading to extrapolate anyone’s behaviour from its context – both Mourinho and Benítez would undoubtedly be interesting company away from the shark-infested goldfish bowl of high-end management – and somehow believe you’re accessing the ‘true personality’. The difference was not so much one of nature as degree (Rafa’s occasional peevishness was an upstairs box room to José’s open-plan lounge- diner). Intense competition does strange things to people.

Where they differed, then, was in their stress reactions, their forbearance, their capacity not to lose their shit. Just as everyone has their price, so everyone has their shit-losing phase-state, where water turns to steam. And for a while, the thing that most made them lose their shit was the sight of each other’s face in the aftermath of victory. Buttons were regularly pushed and, slowly, resentments acquired layers, history, memories. Mourinho, in particular, went for regular transfusions of bad blood and the 38 months of incremental morbo between his Chelsea and Benítez’s Liverpool – arrivistes and aristos who met 16 times in three-and-bit seasons, 8.6% of Mourinho’s games during that first Chelsea stint – would still be there thrumming away in April 2009, 18 months after the Portuguese had been sacked. The once fizzy, now foetid water refused to pass under Stamford Bridge.

Benítez may have been cast as a warm, Castilian breeze to Mourinho’s unpredictable Atlantic squalls, but there weren’t many dark clouds in the latter’s first season in English football as his expensively overhauled squad swept imperiously to the title. Didier Drogba, Arjen Robben, Petr Čech, Ricardo Carvalho, Paulo Ferreira, Thiago Mendes and Mateja Kežman all arrived in the summer, at a cost of £90m or so, while 14 players were moved on, including Juan Sebastián Verón, Hernán Crespo (both on loan), Desailly, Emmanuel Petit, Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink, Mario Melchiot, the lesser spotted Winston Bogarde and Grønkjær, the only one to raise a fee. They beat Liverpool 1-0 at Anfield on New Year’s Day 2005, as they had at Stamford Bridge in October – future Liverpool flop Joe Cole with both winners – and, at the end of February, won the Carling Cup after a 76th-minute Gerrard own goal had taken the final to extra-time, John Arne Riise having thumped in a volley after 45 seconds. Drogba and Kežman poked home from close range, Antonio Núñez’s only goal for Liverpool followed, but Chelsea hung on for a 3-2 win and Mourinho’s first trophy for the Blues.

He wasn’t on the bench to see the winning moments, however, having been sent off for celebrating Gerrard’s own goal with a shushing sign. “I have a lot of respect for Liverpool fans,” Mourinho said later. “What I did, the sign of silence – ‘shut your mouth’ – was not for them. It was for the English press.” This may have struggled to convince a jury of his peers, given that Mourinho’s gesture came during a short 20-yard constitutional along the Millennium Stadium touchline, right in front of Liverpool supporters, with nary a glance toward the press box. Plausible deniability, perhaps, but he wasn’t fooling anyone.

Perhaps some of this WWE-level hammy provocation can be ascribed to Mourinho having courted Liverpool while still at Porto, asking a representative of his, Jorge Baidek, to sound the club out in February of 2004. Much as being overlooked for the Barcelona job in 2008 – the club he had worked for opting for the sophomoric and untested Pep Guardiola, albeit acknowledging the thoroughness and excellence of Mourinho’s PowerPoint presentation – seemed to ignite the most rancorous streak in the him, it is not inconceivable that Mourinho still simmered over Liverpool choosing Benítez, or at least felt spurned enough to forego any graciousness, a characteristically difficult emotion for him to activate. Maybe part of him found particular enjoyment in the identity of the own-goalscorer, too, for he had scribbled Steven Gerrard’s name on that first summer’s Waitrose shopping list – the Portuguese being both a keen consumer of good eggs for better omelettes and untroubled by the apparently implacable problem of Gerrard and Lampard playing in the same midfield. The Liverpool skipper’s head would not be turned, however. Not yet. Another snub carefully logged away, perhaps.

The upshot of these early skirmishes was that two clubs who had barely noticed each other suddenly realised they were now eyeballing. Sky Sports’ propensity to gladiatorialise ‘tribal’ enmities no doubt further stirred up the stands, message boards and phone-ins. A full-blown stoush was imminent.

When the two teams squared off for the first leg of the 2004-05 Champions League semi-finals, Chelsea were on the cusp of wrapping up a first top-flight title for 50 years – and just a second overall – needing only two points from four games to seal things. They had lost only three matches all season: in the league to Manchester City; in the Champions League at the Estádio do Dragão, with Mourinho back in those beautiful blue chairs; and at Newcastle in the FA Cup fifth round. With three victories from three outings against Liverpool, Chelsea were strong favourites and in the psychological box-seat, not something Mourinho ever knowingly glossed over. Yet Benítez coaxed a resolute first-leg performance from a team that had kept just seven clean sheets in 35 Premier League outings. They left Stamford Bridge with a 0-0, although no away goal meant a tightrope against the Mourinho defensive organisation, while losing Xabi Alonso for the second leg through suspension was a bitter blow for a team not overly endowed with world- class players.

Before arriving on Merseyside for the second leg, the champions-elect had won 2-0 at Bolton to secure the Premier League title, yet the Anfield bem-vindo was devoid of ticker-tape. The stadium, shrouded in the receding twilight, heaved with a top-dog-turned-underdog’s yearning to rub the loadsamoneys’ noses in it. “I don’t think I’ve ever heard anything like it before,” said John Terry, “and I don’t think I ever will again. It is the best atmosphere I’ve ever played in. The hairs on my arms were standing up”. As the Kop belted out its anthem, “You’ll Never Walk Alone”, a fan held up a marker-pen-on-cardboard placard that read, “You’re not buying this one, Chelski,” neatly encapsulating the specific nature of the burgeoning beef. Liverpool, without a league title in 15 years, resented the speed at which Abramovich’s money had helped Chelsea negotiate football’s snakes and ladders, and so took to deriding the nouveaux riches Londoners with the refrain, “You ain’t got no history.” Abramovich himself seemed partly to agree, for at half time, while his executives complained about the legitimacy of Liverpool’s goal, he gave instructions to have a similar song composed for the Chelsea supporters. “We need a song, like the song they have. Find a songwriter. Pay him to write a song.”

The goal in question was of course Luis García’s so-called ‘ghost goal’, the Spaniard nosing the opportunity after Milan Baroš had latched onto a deliciously soft-faded pass from the outside of Gerrard’s right foot in the fourth minute only to be poleaxed by the onrushing Čech. García dinked the loose ball goalwards, via Terry’s thigh, with the covering left-back, William Gallas, clearing on/over the line. “You can say the linesman’s scored. It was a goal coming from the moon or from the Anfield stands,” groused Mourinho, implying the Kop had not so much sucked it in as mind-fucked the referee into giving it. “The best team lost and didn’t deserve to lose. They didn’t score in the semi-final, but I accept that they beat us,” he would say months later, failing to accept his team had been beaten. Football’s parochial parallax errors meant that others in red saw it over the line – you wonder how they can ever resolve these matters – with Benítez later writing, in Champions League Dreams, that he knew it was a goal because his secretary, Sheila, sitting with other club employees level with the goal-line, had said so. Open and shut. In any case, the swift Scouse rebuttal was that, if it wasn’t in then it was a penalty and a red card for Čech. With Carlo Cudicini on the bench and a proclivity for sieges, Mourinho may happily have settled for that.

The rest of the game crackled without really working up a decent current. In his book, Benítez described Chelsea’s approach as “long balls up to their powerful striker”, adding caustically, “such a method is a little bit of a lottery, not particularly scientific, maybe a little crude. There was no subtlety in their play.” The Iberian cognoscenti were not impressed. Real Madrid’s sporting director Jorge Valdano famously compared the game to “shit hanging from a stick”, which might even be a compliment in certain circles: the Dada movement or coaches prioritising defensive resilience. With just one English finalist in the 20 years since Heysel – Manchester United’s Camp Nou heist against Bayern – English sides were very much still seen as playing an unrefined game, not yet ready for the top table. Tastes were further offended when Dida, Cafu, Stam, Nesta, Maldini, Gattuso, Pirlo, Seedorf, Kaká, Crespo and Shevchenko were beaten in Istanbul by a team containing the errant limbs of Djimi Traoré, despite taking a 3-0 lead. The facts are yet to emerge, but one can safely assume that the previous manager to lift the trophy didn’t text congratulations to his successor.

Benítez, then, had finished his transitional season as an Anfield immortal while losing 14 league games. This translated to fifth place, 37 points adrift of Chelsea and three behind Everton, whose greatest team of the modern era were denied European qualification by Heysel and who now looked likely to be excluded again as Uefa scratched its head over whether five teams from one country could be permitted Champions League football. They put the onus the FA, who insisted that the four English qualifiers would be the four highest- placed teams (thankfully, Twitter was still a glint in Jack Dorsey’s eye at this stage).

In the end, Uefa relented – after all, the expanded Champions League structure was in part designed to prevent the sheer horror of clubs powerful enough to win the European Cup failing to qualify the following year through their domestic league – and allowed Liverpool into the 2005-06 competition, it being decided they would enter the first qualification round and Everton the third. The European champions’ defence of their crown thus began on July 13 against Total Network Solutions of Oswestry and Llansantffraid-ym- Mechain (the TNS since reworked into a slightly more evocative The New Saints FC), before breezing past FBK Kaunas and CSKA Sofia. Everton, meanwhile, drew Villarreal, Juan Román Riquelme, Diego Forlán et al winning 4-2 en route, ultimately, to a semi-final exit to Arsenal.

Eight days before scoring a hat-trick in the first-leg against TNS at Anfield, Liverpool’s talismanic homegrown hero of Istanbul had sent tremors through the club – or rather, a sense of nausea – after putting in a formal transfer request, “a hand-grenade rolled into the Liverpool boardroom” as he described it in his autobiography. With Liverpool’s 30-point gap to the Arsenal ‘Invincibles’ having widened to 37, the player’s ambitions provided an opening for a charming salesman holding a coveted piece of silver. In the lead-up to Istanbul, Chelsea again pursued Gerrard aggressively. A £32m bid was rejected by Liverpool, while Gerrard initially turned down an improved contract offer of £100k per week. Just six weeks after Istanbul, however, came the transfer request and a short statement: “This has been the hardest decision I have ever had to make. I fully intended to sign a new contract after the Champions League final, but the events of the past five to six weeks have changed all that.” His book depicts that long Tuesday, July 5 as “the most emotional” day of his life, which he spent sitting at home “drained of energy”, watching rolling news footage of fans protesting at Melwood – one having been prompted to burn Gerrard’s number 8 shirt for the cameras – while “eating paracetamols like smarties”. The club held firm and two days later came Gerrard’s U-turn: “I can assure everyone that this won’t be happening again next summer or ever again so far as I’m concerned.” Gerrard’s subsequent offer to give up the Liverpool captaincy was rebuffed. Anger on Merseyside quickly dissipated, part of it converted to resentment in west London and a special animosity toward a player who had flirted with their gym-toned, Insta-perfect smoulder but in the end got hitched to his childhood sweetheart.

Once the dust had settled and the qualifiers finished, England’s Champions League representatives were finalised as Liverpool, Chelsea, Manchester United and Arsenal, as they had been the previous year and would be for the following four. Liverpool were not given ‘association protection’ in the draw, although the only other member of the nascent Big Four they could feasibly meet in the pool stage was Chelsea, since Arsène Wenger’s and Alex Ferguson’s teams were in the same (top) seeding pot. Inevitably, they drew Chelsea, which meant 180 goalless minutes and two more extremely shitty sticks. It was like competitive bus- parking. Or competitive buck-passing.

After the 0-0 at Anfield, in which Liverpool had three vociferous penalty appeals turned down in an otherwise turgid affair, Benítez suggested that, “Arsenal play much better football than Chelsea. They win matches and are exciting to watch. Barcelona and Milan too. They create excitement, so how can you say Chelsea are the best team in the world? They are scared of Liverpool,” to which Mourinho’s response was predictably prickly: “They have to defend or wait for a mistake for a goal. When they play against us face to face they can’t win. We deserve more respect: not from Liverpool but from people in general.” Leaving aside whether Mourinho understood the difference between respect and adulation, the relationship between the teams and their managers had gone subcutaneous. Or hypodermic: under the skin and plenty of needle. Meanwhile, photocopiers were busy printing out pertinent quotes for each other’s dressing room walls.

The Benítez diss took a certain amount of huevos against a better-tooled opponent and, four days later, those eggs would be all over his face as Chelsea inflicted Liverpool’s heaviest home league defeat since 1969. Frank Lampard opened the scoring from the penalty spot in a 4-1 rout that left Liverpool 17 points adrift of the runaway leaders (albeit with two games in hand, having missed games while seeing off the CSKAs, Sofia and Moscow, the latter beaten 3-1 in the Super Cup). He was promptly booked by Graham Poll for his celebrations, a reprisal of the Mourinho shush gesture from Cardiff. The José juju had infected even the more mild- mannered players and become pervasive.

In the return fixture, with Liverpool 2-0 down, Pepe Reina was sent off for grabbing Arjen Robben round the throat in the melée following his reckless, feet-off-the-ground scissor tackle on Eiður Guðjohnsen. The Dutch winger’s relationship with gravity was always problematic, his likely casting by Wim Wenders remote, and a few theatrical rolls in the penalty area, as though just having freed himself from a Tony Soprano garrotting, was enough to convince the referee, Alan Wiley. Asked to comment on the incident, Benítez simply said he was “in a hurry because I must go to hospital”. It was all largely immaterial. Chelsea romped to a second straight league title – leading from pistol to tape – but in terms of their growing feud with Liverpool, the Merseysiders would have the last laugh that season.

Neither team had advanced beyond the Champions League last 16 – Liverpool dumped out 3-0 by Benfica, Chelsea losing 3-2 to Barcelona after Asier del Horno had been red-carded at Stamford Bridge for a foul on the Catalans’ promising new starlet, Leo Messi – and both had lost at the first hurdle in the League Cup. Liverpool had also been beaten 1-0 by São Paulo in the World Club Cup, Benítez’s father passing away while he was in Tokyo. So, for these trophy-addict managers, their FA Cup semi-final encounter at Old Trafford, which would have been testy at the best of times, became positively volcanic.

Riise opened the scoring with a free kick, shifted a yard then curled through a broken wall at shin height, an unusually deft strike for the Norwegian, before Luis García dipped one over Cudicini to double the advantage. Reina then rushed out to deal with a dropping ball from the head of a stooping Riise – who could easily have cleared with his right foot, an error of judgement and technique that would be reprised three years later, with graver consequences – and missed his punch, allowing Drogba to head into the empty net for 2-1. But Liverpool held on. Mourinho refused to shake Benítez’s hand at the final whistle, nor did the managers exchange even a courteous word afterwards.

Liverpool went on to win the final against West Ham on penalties, of course. However, Benítez, like Gerrard, wasn’t satisfied with being a cup team, notwithstanding that season’s 82-point haul being the club’s best in the Premier League era. Envious glances toward west London only heightened the Spaniard’s frustrations over Liverpool’s budgetary constraints – his inability, unlike Chelsea, to add the two or three world-class signings that might have turned an on- their-day team into an almost-every-day one, like Chelsea. Mourinho’s self- aggrandising sleight-of-hand in depicting the league as a level playing field in which the key variable was managerial competence rankled further. Such feelings might have remained submerged without cup draws throwing the teams together so frequently, the accumulation of which drew the antipathy to the surface like pus.

Indeed, in Champions League Dreams, Benítez describes bumping into Mourinho on the stairs up to the Anfield boardroom after his first home match against Chelsea, on New Year’s Day 2005. “Despite the events of the game – when a tackle from Frank Lampard had broken [Xabi] Alonso’s ankle and [Joe] Cole had scored late on to deprive us of a well-deserved victory – we stopped to talk, a polite conversation about our respective work and the ambitious plans of Chelsea’s owner, Roman Abramovich, for that summer’s transfer market.” Notwithstanding the fact that Chelsea had won 1-0, only depriving Liverpool of a draw, this ostensible depiction of cordiality could be interpreted – should one take up a position between the lines – as a carefully calibrated piece of plausibly deniable shithousing, with its score-settling over how the score was settled and passing reference to Mourinho’s budget.

For Mourinho, of course, some of the rancour may have been down to his rejection by the Liverpool board. Some could be ascribed to the Gerrard farrago (presumably José didn’t disclose this part of Chelsea’s summer transfer plans to Rafa), the midfielder’s ultimate rejection of Chelsea depriving Mourinho of both another high-grade weapon for his pursuit of further Champions League success and a potent symbol of the post- Abramovich New World Order in which to rub Scouse noses. Yet part of it was undoubtedly caused by Benítez’s refusal to accept financial determinism in those “face to face” encounters that “they can’t win” but did in fact win on some of the biggest occasions. Indeed, after the FA Cup semi-final, Mourinho was forced to realign the barbs, to shift the goalposts: “Did the best team win? I don’t think so. In a one-off game maybe they will surprise me and they can do it. In the Premiership the distance between the teams is 45 points over two seasons.” So there.

If Chelsea’s spending in the summer of 2004 and attempts to land Gerrard a year later had irked Benítez, then their business leading into the 2006-07 campaign could be said to mark the first step in the unravelling of Mourinho’s relationship with the Chelsea hierarchy. The club’s major recruit, Andriy Shevchenko, scored on his full debut – the Community Shield curtain-raiser against the new old enemies, Liverpool – chest-trapping a floated diagonal from Lampard two minutes before half-time and, without need of another touch, sliding home. It was the finish of an apex predator and cancelled out Riise’s ninth- minute opener, a 60-yard unchallenged run and 30-yard punt through Cudicini’s hands. The camera cut to Roman Abramovich, clapping exultantly. It was, of course, a false dawn – both in the game, in which one of Liverpool’s summer signings, Peter Crouch, headed the winner (Mourinho again declining to shake his opposite number’s hand), and in the long term, as Shevchenko would score just four Premier League goals all season. (At the time too politic openly to criticise an Abramovich favourite, Mourinho would later say – dextrously positioning himself as, if not a victim then a begrudging recipient of an unwanted gift – “[Shevchenko] was not my first option but the club gave him to me as a second option,” adding that the Ukrainian was “too used to being treated like a prince” in Milan.)

Another of Chelsea’s major signings, Michael Ballack – they also splurged on Salomon Kalou, Jon Obi Mikel, Khalid Boulahrouz and Ashley Cole – managed to get himself red-carded five weeks later when the two clubs resumed hostilities in the Premier League, although Drogba’s first-half goal was enough to secure the Blues a win. Nevertheless, after five straight league defeats to Chelsea, Benítez finally got off the mark in January thanks to two more of his summer signings: Dirk Kuyt scoring after four minutes and Jermaine Pennant thumping a 25-yard angled volley down off the crossbar after 25, as the makeshift centre-back pairing of Paulo Ferreira and Michael Essien struggled to cope. But Liverpool were well off the pace in the league and, having been knocked out of both cups by Arsenal (including an astonishing 6-3 home loss in the League Cup), the Champions League was their only chance of silverware.

Two weeks before the first leg of their last-16 tie with Barcelona the Camp Nou – a 2-0 win famous for Craig Bellamy’s golf-swing celebration, a somewhat questionable allusion to his drunken hotel-room confrontation with the karaoke-averse Riise, the other goalscorer, on an Algarve retiro – the club was bought by Tom Hicks and George Gillett. Their first game at Anfield was Liverpool’s 1-0 defeat in the second leg, and they were unable to work out why the supporters were cheering at the end. Liverpool’s hoped-for Roman road to title glory would of course not only fail to materialise – with the two owners’ relationship quickly fracturing into non- communication – but would lead to the nadir of the 2010-11 campaign and a Roy Hodgson team that included Paul Konchesky, Christian Poulsen, Milan Jovanović and a busted Joe Cole. In the middle of it all, Benítez largely kept his counsel and worked with what he had. Largely. Javier Mascherano had arrived on loan from West Ham in the January window and PSV Eindhoven were dispatched easily enough in the quarter- finals. Chelsea, meanwhile, had squeaked past Porto and Valencia, 3-2 in both, a 78th-minute Ballack winner in London seeing off Mourinho’s former charges and a last-minute Essien winner in Spain depriving Rafa of a semi-final reunion at the Mestalla. Ding-ding, Round Three. Or, from another perspective, Fourteen.

Liverpool were a little lucky to escape Stamford Bridge with a 1-0 defeat in the first leg. Drogba ran the back line ragged in the opening half-hour, although failed on several occasions to play the obvious, chance-creating pass. The one time he got it right led to the goal, the Ivorian muscling past Daniel Agger on the right, chopping inside and squaring to Joe Cole, who steered home expertly with his left foot while sliding and tumbling after a small tug on the shoulder from Álvaro Arbeloa. Chelsea failed to create a clear chance in the final hour, however, while Čech was only seriously discomforted once all night, by a left- foot Gerrard volley from just outside the box. The familiar caginess and torpor had overwhelmed a bright beginning, creating a game without twists, only sticking.

A week later at Anfield and Benítez was again sniping. “I’m sure Chelsea do not like playing Liverpool. When they are talking and talking and talking before the game”, he theorised, talking and talking before the game, “it means they are worried. Maybe they’re afraid?” In case anyone was in any doubt that “Chelsea” was a synecdoche for José Mourinho, he went on, “We have our special ones here. They are our fans, who always play with their hearts. We don’t need to give away flags for our fans to wave. Our supporters are always there with their hearts, and that is all we need. It’s the passion of the fans that helps win matches, not flags.” Not quite Jürgen Klopp, but Rafa was dialling the Anfield twelfth man up to 11.

Liverpool established parity in the 22nd minute when Agger swept home an exquisitely executed free-kick routine, held back especially for the occasion. Attacking the Kop in the second half, Kuyt thumped a header against the bar not long after a Crouch downward header had somehow been kept out by Čech’s spidery limbs. Chelsea’s big moment came with 15 minutes left of normal time, but Carragher turned desperately over his own bar from inside the six-yard box with Drogba primed for a tap-in. Extra-time brought only tension, and a penalty shoot-out seemed inevitable; Geremi, one of only six players on the bench for a depleted Chelsea, was brought on especially for that endgame.

Chelsea won the toss and chose the Anfield Road End, but Robben and Geremi’s kicks, either side of a Lampard conversion, were saved by Reina. Benítez watched on, cross-legged on the Anfield turf – not to exude calm, as is often supposed, but because he was blocking the view of those in the Paddock behind the dugouts – as Kuyt, Liverpool’s fourth man up after Boudewijn Zenden, Alonso and Gerrard, sealed the win. “I walked onto the pitch, as I always did,” wrote Benítez in Champions League Dreams, “hoping to catch one or two of my players to pass on a little piece of advice, something that had occurred to me during the match that they could improve for the next game… I did not get very far before Craig Bellamy put his arm around me, beaming. ‘You’, he said, giving me a hug, ‘are a fucking genius.’ I have never seen him so happy. I’m not sure I have ever seen anyone so happy.”

Mourinho, of course, wasn’t happy. “The best team lost,” was his terse assessment, which was correct if looking at the league table, where Liverpool, in third, finished 15 points adrift of Chelsea, themselves six behind a resurgent Manchester United. But it wasn’t an accurate depiction of a tight, cagey match and smacked of deflection from his team’s lack of creativity over the two legs. Not that Liverpool were too bothered as they celebrated hard and late at the Sir Thomas Hotel in the city centre, Gerrard briefly hitching a lift home on a milk float when unable to flag down a taxi.

Liverpool lost the final in Athens, of course, two typically prosaic goals from Filippo Inzaghi giving AC Milan a 2-1 win, with Kuyt’s 89th minute consolation too little, too late. In jubilation as in despair, Benítez’s instinct was for immediate analysis, and with soft beds and low ceilings in their insalubrious hotel not assisting sleep, he and his closest staff walked for four hours round the city in the rain, returning at 7am. Conclusion: a quick, direct striker was needed, as was quick, decisive dealings in the transfer market, thoughts that the Spaniard had made abundantly clear in his post-match press briefing.

The following season’s Champions League campaign would barely get going before Mourinho was sacked in the wake of a tepid 1-1 home draw with Rosenberg, albeit not before a 16th and final clash with Benítez’s Liverpool, Lampard’s penalty cancelling out new £20m signing Fernando Torres’s opener in a game featuring nine yellow cards. Mourinho’s P45 was as much to do with the exhausting siege-mentality atmosphere that had accreted at Stamford Bridge as it was about results, with 11 points from six league games not an irretrievable disaster.

Meanwhile, Benítez had heard from trusted sources that Liverpool’s American owners had sounded out Jürgen Klinsmann, which they at first denied and then explained away as a contingency should the call of Real Madrid prove too tempting for the Spaniard. Benítez was trying to get answers from Tom Hicks about transfer targets and was told, via email and in caps, to “focus on coaching and training the team you have.” Furious, Benítez gave a truculent press conference in which he repeated this phrase over and over. He then broke the habit of a lifetime and wore a tracksuit for the 3-0 win at Newcastle, later insisting that it was because he had forgotten to pack his shoes. Before the next game, at home to Porto, the fans protested against the US owners. But the storm abated.

All of this meant that Benítez and Avram Grant were in the dugouts for Chelsea’s 2-0 Carling Cup win over Liverpool in December, in which Crouch was sent off for a two-footed lunge on Jon Obi Mikel two minutes after Lampard had given the Blues the lead, Shevchenko sealing things in the 89th minute. In February, two weeks before Chelsea lost 2-1 to Tottenham in the Carling Cup final, Liverpool were back in west London, leaving with a 0-0 draw, the seventh straight visit to Stamford Bridge in which Benítez’s men had failed to score. The teams then rendezvoused in the Champions League semis for the third time in four seasons, Liverpool having beaten Inter (3-0) and Arsenal (5- 3), Chelsea eliminating Olympiacos (3-0) and Fenerbahçe (3-2).

The first leg saw Liverpool create the better chances, Kuyt opening the scoring from close range just before half-time after dispossessing Lampard on the edge of the Chelsea box and getting on the end of a shank from Mascherano, flooring Ashley Cole with a perfectly timed bum-barge, then slamming under the advancing Čech. But the Czech bounced back in the second half to deny Torres and tip over a Gerrard rasper, and five minutes into injury-time Chelsea swung the tie decisively their way. Kalou, collecting the ball from a throw-in on the goal-line behind Liverpool’s right back, was allowed to turn and flash a cross across the six-yard box; Riise misread the trajectory and instead of clearing with his right foot stooped to head away but succeeded only in diverting the ball powerfully into his own net. Still no Chelsea player had scored in 390 Champions League minutes at Anfield, yet the own goal would prove decisive.

Mourinho may have gone, but the tensions hadn’t entirely lifted with his departure. Notwithstanding the lugubrious Grant, the dynamic between the clubs had transcended the personalities involved, as though the strife had burrowed itself into the institutions, such that if the personnel changed the acrimony would remain. Not only that, the ghost of Chelsea managers recently past still hovered over the fixture: “How many championships has Benítez won since he joined Liverpool?” Mourinho enquired, rhetorically, from his sabbatical soapbox. “None. And how many names were suggested by the press to replace him? None.”

Prior to the second leg, Benítez – no doubt hoping the Italian referee Roberto Rosetti was listening – had labelled Drogba a diver, not entirely inaccurately although perhaps injudiciously (there are certain players you just don’t sledge). Sure enough, when Drogba opened the scoring, drilling a parried Kalou drive past Reina at the near post, he celebrated with a pointed dive toward the corner flag, abetted by rain that at times fell torrentially, and then continued his celebrations in front of the dugouts. Later, he would let his mouth do the talking: “Benítez was a manager I respected a lot. Until now, I found him not only very competent but also classy. But he has really disappointed me here. His words demonstrate a weakness. A top manager would never go so low to attack a player [Mourinho’s CV makes interesting reading here]. Maybe he should concentrate on his own team’s game and if he wants me to stay on my feet, maybe he should tell his defenders to stop hitting me.”

Torres equalised in the second half, a predatory two-touch finish having drifted behind Carvalho, drawn out toward Benayoun in the hole. After that, on a heavy, energy-sapping pitch, the game lurched nervously into extra-time, largely against the tone of an encounter that, given the adversaries, had been relatively open and wild. The prize was a meeting with Manchester United in Moscow, a Paul Scholes strike at Old Trafford the previous evening enough to settle an otherwise goalless tie with Barcelona. And it was yet another Lampard penalty – converted just two days after his mother had died from pneumonia – that gave Chelsea the advantage-that-doesn’t-really-change- the-other-team’s-task. Drogba wasn’t yet done, though, and his second, an almost identical finish to his first, gave Liverpool a mountain to climb, partially scaled by Ryan Babel’s 117th-minute 35-yarder that squirmed through Čech’s greasy gloves. But the clock ran out on a pulsating game, the first between the sides in Europe that had allowed a little chaos into the patterns. Chelsea had finally bested Liverpool in the Champions League.

It was, of course, all for nothing, a small slip of John Terry’s standing foot on the recently-laid Luzhniki turf ceding the penalty shoot-out advantage gained by Ronaldo’s miss, before Nicolas Anelka’s nervy effort sealed their fate. There might have been a few smiles on Merseyside had it not been for the identity of the victors. For Chelsea the heartache had been compounded by United pipping them to the title by two points. The solution? ‘Big Phil’ Scolari.

20 meetings in four seasons had created in two clubs without deep roots to their hatred – notwithstanding the links between a Chelsea fringe and far-right nationalism and Liverpool’s conception of itself as a city-state apart, steeped in internationalism and socialism – a sort of animosity fatigue, two heavyweights all out of trash talk, shredded by the cumulative exertions, both having exposed their secrets and vulnerabilities. Luiz Felipe Scolari was an avuncular figure who was unlikely to elicit any acerbity from his Liverpool counterpart. “He is a good manager with a lot of experience and passion,” dead-batted Benítez when invited to comment on the new man. “Chelsea are a good team with a strong squad and I thought Avram Grant did a good job for them, and Scolari will want to do the same”.

The Brazilian wouldn’t make it through to spring, of course, although Chelsea started the campaign well and were the early title pacesetters. However, in late October, their 86-game unbeaten Premier League home run, stretching back four years and eight months to Claudio Ranieri’s tenure, was ended with a 1-0 defeat. To Liverpool. The goalscorer was Xabi Alonso, soon to be unsettled out of the Anfield door by his manager’s attempt to swap him for Gareth Barry, a decision guided by the Premier League’s incoming ‘homegrown rule’, Benítez later admitted.

Liverpool’s summer intake – in descending order of expense: Robbie Keane, Albert Riera, Andrea Dossena, Diego Cavalieri, David N’Gog and Philipp Degen – didn’t immediately smack of the kind of improvements needed to mount a credible title challenge, but that is of course how things panned out, the only one of Benítez’s tenure. They led the table through much of December – when Benítez had two operations on his kidneys and when Steven Gerrard, after a few too many Jammy Donuts at the Lounge Inn, in what came to be known ‘the Phil Collins incident’, was charged with affray – and on into January, when Benítez chose the day of Manchester United’s game with Chelsea to “talk about facts”. But those months saw a run of seven draws in ten undefeated games, a fatal loss of momentum. A second and final Premier League defeat of the season at Middlesbrough on the final day of February left them third, but from there they would win 10 of their final 11 games, including the famous 4-1 rout at Old Trafford.

By then, of course, Keane had been sold back to Tottenham at a £6.5m loss. Fernando Torres, buoyed by scoring the only goal of the final at Euro 2008, was suffering from Second Album Syndrome, his signature inside-left penalty-box feint not quite as effective as his debut season, when he netted 33 times, including three hat-tricks. All of which left a team with a spine that didn’t suffer in comparison with any in Europe relying on N’Gog as its back-up striker, Kuyt long having been converted into an industrious and semi- defensive wide forward.

Nevertheless, in February they completed the double over Chelsea, two late, late Torres goals in front of the Kop securing a 2-0 win in which Lampard had been sent off for a tackle on Alonso, although his suspension was later rescinded. Chelsea drew their next game, against Hull – completing a run of 12 league games with just four wins – at which point Scolari was fired. Ray Wilkins came in as interim boss for the FA Cup win at Watford – Chelsea would go on to beat Everton in the final – after which Guus Hiddink, at the time managing Russia, arrived for the remainder of the season.

Scolari had overseen Chelsea’s Champions League qualification from a group comprising Bordeaux, CFR Cluj and AS Roma, with Hiddink in situ for a tight 3-2 aggregate win over Juventus in the last 16. Liverpool, meanwhile, squeezed past Standard Liège 1-0 in qualifying thanks to a 117th-minute Kuyt strike, before coming through a group with Atlético Madrid, Marseille and PSV unbeaten and in first place. Real Madrid were dismantled 5-0 in the opening knockout tie, Yossi Benayoun nicking a 1-0 win in the Bernabéu before a 4-0 rout at Anfield, arguably the signature performance of the Benítez reign. Dossena scored the fourth, as he would at Old Trafford four days later, his only two goals for the club.

When Liverpool and Chelsea’s names were inevitably paired in the quarter- finals the Merseysiders were considered marginal favourites. True, Chelsea had removed the primate from their backs, but Liverpool led them by three points in the Premier League by the time the home first leg rolled round and, according to the Uefa coefficient, were the top-ranked club in European competition over the previous five years. So Anfield welcomed Chelsea again, only this time – whether you see the candlesticks of literalism or the opposing faces of metaphor – the visiting coach was either parked outside the ground or schooled in the Dutch stijl of a proactive, possession-based football of intricately moving parts. The upshot was much the same: erstwhile tree appendages with the excrement jet-washed from them.

Torres opened the scoring after six minutes and since the only Champions League goal Chelsea had managed at Anfield in their previous four visits had been scored by Jon Arne Riise, now playing in Rome, the swell of expectation was that Liverpool might be able to kill the tie in the first leg. But then football intruded upon narrative, the game turning on two headed goals from Branislav Ivanović either side of half-time, the first knocking the wind out of Anfield’s sails, the second ripping them from the masts. When Drogba added a third five minutes later, Liverpool went into shock. Chelsea’s goals had not owed much to the Dutch School and this was not the script for these teams’ Champions League tussles, which, excluding the previous season’s extra-time dénouement, had yielded seven goals in eight lots of 90 minutes. Liverpool faced the prospect of having to scoring at least three goals at Chelsea in six days’ time, the same total they had managed there in ten visits under Benítez, all of them scored in the previous two. They would need Sherpa guides and oxygen.

Between the two legs, Liverpool won 4-0 at home to Blackburn while Chelsea almost unwalloped Bolton 4-3 at home, storming into a 4-0 lead on the hour before three goals in eight minutes gave Gary Megson’s team 15 minutes to complete the unlikeliest of comebacks, but a late Gary Cahill shot flashed wide and that was that. Truth being in the eye of the beholder, the Chelsea supporters could write it off as complacency while the Liverpool fans were able to see a team capable of conceding three at home. A further source of optimism was the yellow card given John Terry at Anfield for a barge on Pepe Reina – Terry telling the media that Reina himself thought the card harsh – that would keep the Chelsea captain out of the second leg. There was also the admittedly less tangibly propitious fact that, four days before the first leg, four miles up the A59, Mon Mome, a 100-1 outsider, had won the Grand National. Liverpool would still travel to Stamford Bridge with hope in their hearts.

By now the Champions League anthem was blasting through the speakers and Liverpool were readying themselves for the club’s 300th game in European competition. It was also the eve of the 20th anniversary of Hillsborough, and there was urgent discussion with Uefa in the aftermath of the draw to ensure Liverpool avoided the Tuesday/ Wednesday cycle, which would have meant a clash and the players and staff almost certainly having to miss a memorial service at Anfield. Michel Platini made the right noises, saying that he and Uefa would “do our utmost” to avoid such a scenario, although once the wishes of TV companies were set aside there really was no reason at all not to simply ink Liverpool into April 8 and 14.

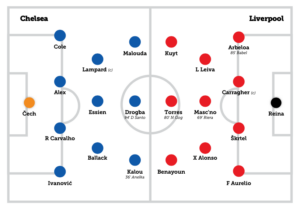

Common sense prevailed, however, and the stage was set, although two leading protagonists were absent. Gerrard was nursing a groin strain (the more tin-foil crew believed he was being saved for the title run-in) and, like his Chelsea counterpart, had to sit the game out. This left only Čech, Lampard, Drogba and Carragher as ever-presents, the Walter Whites, Don Drapers, Omar Littles and Tony Sopranos of this heaving ten-part saga. Lucas Leiva was asked to fill the skipper’s shoes in the number 10 role; Carvalho stepped in alongside Alex, the Brazilian who had played under Hiddink at PSV, loaned out by Chelsea, and would start every game in the Dutchman’s short interregnum.

The first big chance of the night fell to Fernando Torres on 13 minutes, after neat link up between Benayoun and Kuyt slipped him in, between the centre backs, but the Spaniard, obliged to take it first time, scooped over. “If Liverpool are going to pull this off you feel they’ve got to take most, if not all of their clear-cut chances,” said Clive Tyldesley on commentary, not yet aware that the normal Chelsea- Liverpool rules had been binned.

Lampard drilled a free-kick wide, then Carvalho conceded a soft free-kick for a push on Torres, around 30 yards from goal and out toward the Liverpool right. Čech eschewed the protection of a wall and stood a few yards off his line, just beyond the middle of his goal, readying himself to punch or catch the inswinger. Fábio Aurélio – the first Brazilian to play for Liverpool, a versatile left-back who worked under Benítez at Valencia and had been brought in to provide a little more guile than Riise – took two steps toward the ball while Čech, fatally, took one toward where Martin Škrtel’s bony head was likely to intercept the anticipated cross. Only, Aurélio, with the willowy disguise of a Federer drop shot, whipped a hard, low skimmer perfectly inside the near post – “Oh, he’s gone for goal,” gasped Tyldesley, his voice going up an octave – so perfectly that Čech couldn’t salvage his initial error with a desperate dive and simply fell to his knees as he stumbled forlornly back across the goal. “Look at that. Look at that. Surprise, surprise. Petr Čech totally embarrassed by a brilliant piece of improvisation from Fábio Aurélio”.

Emboldened, Liverpool launched themselves at Chelsea and, just before the half-hour mark, another free kick was won in a similar spot to where the opening goal had burst forth from Aurélio’s imagination. This time, though, the ball was slightly further out, slightly wider, and with the element of surprise having gone (in any case, Čech thought it prudent to have a wall). This time, the ball was indeed curved in over the penalty spot, toward an offside-looking Škrtel, who fluffed a sidefoot volley. The whistle blew. Tyldesley assumed it was offside, but then noticed the referee, Luis Cantalejo, pointing to the penalty spot. Ivanović had his arms locked around Alonso, dragging him backward to the floor as though garrotting him, and the Basque stepped up to send Čech the wrong way from the spot. Tyldesley was by now quite giddy: “Anything is possible. Anything.” The camera cut to an exultant Gerrard. Less than a third of the way in, Liverpool were two-thirds of the way to their target.

Hiddink was quick to act, taking off Kalou ten minutes before half-time and replacing him with Anelka. Chelsea started to cause a few problems at the other end, Ivanović getting in a tangle in the box with Carragher then heading wide from a Malouda free kick. But the best chance in what remained of the first half fell to Kuyt. Aurélio was again instrumental, hitting a flat cross just beyond the centre of the goal that the Dutchman tried to loop back over Čech, who back-pedalled and pawed it away brilliantly, a moment of certainty in an otherwise shaky display. In the second half, it would be his opposite number who got the jitters.

Not that Čech himself looked any more composed, rushing out to try to intercept a clever through-ball for an out-to-in Kuyt run into the inside-left channel; the Dutchman got there first, Čech was obliged to pursue and did just enough to prevent Kuyt spinning and curling an immediate shot toward the untended goal. It was 3-3 but Chelsea were on the ropes and were Liverpool to score next the likelihood was that there would only be one winner. At which point a Reina error turned the momentum upside down.

Anelka, wide on the right and running even wider, two defenders tracking him, was allowed to fizz a speculative cross toward the near post, where Drogba, on the six yard line and with Škrtel behind him, stuck out a boot and lightly deflected the line of the ball from the centre of Reina’s body toward his left hand, like a thick-edge for a wicketkeeper standing up to a spinner. Only, where the latter would have next to no chance of taking the catch, Reina ought to have done much better than snatchily palm the ball into his goal like an ill-timed pinball flipper. Tyldesley duly informed the audience that the 4-3 didn’t change Liverpool’s task, forgetting that scoring the one goal they needed would now come with a penalty shootout clause as opposed to being handed the keys.

The stadium was lifted and Chelsea responded, winning a free kick 25 yards out, a couple of yards right of centre, after Malouda fell theatrically to the floor. Drogba, ineffectual until his goal, struck a sidefoot shot on the valve and the wobbling ball rippled the side-netting, eliciting quickly aborted celebrations from the almost 40,000 Chelsea supporters. But they were soon roaring when another free kick was won, slightly further out and slightly less central, and absolutely welted home by Alex – nicknamed ‘the Tank’ in the Netherlands – hitting slightly across the ball to give it fade. “That’s in. That’s in”, Tyldesley chirped, while Jim Beglin simply asked: “Can you hit a ball any harder?” Again, however, there were question marks over Reina’s efforts, the shot, after all, hitting the back of his net almost centrally, with his hands too slow to snap up to the flightpath.

For those minded to understand second- half reversals of a game’s momentum as the inevitable outcome of some Braveheart-style rhetorical intervention from the coach – that familiar post hoc, ergo propter hoc causal inference of “I don’t know what the manager said to them at half-time, but it’s worked” – Hiddink’s post-match remarks offered an insight into what was said in, or to, the “angry” dressing room. “Playing against Liverpool, who are a good team tactically, you can’t give them that much space. We dropped back too much, should have defended further up the pitch and cut out the spaces for them to attack. We lost too many duels in the first half. At half-time tactically and mentally we said, ‘Hey guys, this is not the way to start the second half.’” He had a point.

By then Drogba was rampant, as Liverpool’s shape melted away in the desperation. Carragher stumbled as he tried to tug back the Ivorian, played in behind, who squared for Ballack, a golden chance sidefooted too close to Reina. Then Torres, back to goal, took a sharp touch to get it out of his feet and curled a shot a foot or so wide from 30 yards. All inhibition had disappeared from the game. It was Hagler-Hearns. Every attack promised a goal.

With 15 minutes left, Drogba sprung the back line again, this time with a lateral run, replays suggesting he was marginally offside. Taking Ballack’s clever pass in the inside-left channel, he sorted out his feet and drove into the box, Škrtel going to ground, before squaring with his left foot. Anelka’s run took Carragher to the near post, leaving Lampard to score the quintessential Lampard goal: a second-wave run into the box and meaty sidefoot finish that Reina got enough of a hand on to send it bouncing sharply up into the roof of the net. “Chelsea are heading for the Nou Camp,” exclaimed Tyldesley. “The first half was a horror story. But this has been a script you just couldn’t put down. And it’s Chelsea … who are going to be the winners … on the final page.”

Except, this was European arthouse, and really we had only reached the end of Act Two.

For Liverpool, the time for discretion had long gone. They needed three goals in 14 minutes plus stoppage time: enough for at least seven by Istanbul standards, but still odds-against. Five precious, precious minutes had slipped by when the ball dropped to Lucas Leiva 25 yards out and his desperate potshot was diverted past a wrong-footed Čech off Essien’s hip. “He’s bought the ticket so he had a chance,” said Beglin.

Before the MBMers had chance to punch out a description of Lucas’s strike, Dirk Kuyt’s bullet header from a poacher’s run in front of Carvalho was bulging the net. Two in two: 6-5! Mayhem on Merseyside. Liverpool fans disbelieving, believing. OMGs and football, bloody hells everywhere. “Liverpool are rolling away the stone again,” cooed Tyldesley, a reference either to Indiana Jones, Matthew 28:2 or Mott the Hoople. One more goal – five at the once impregnable Stamford Bridge! – and they were through.

A Drogba half-chance came and went, N’Gog nearly went clean through. Clive’s voice became tremulous, orgasmic, the drama proving too much. Rafa paced the touchline, his habit of conveying complex tactical instructions through subtle hand gesticulations giving him, amid the utter maelstrom that the game had become, the air of a psychotic whose specific delusion was imagining himself to be a traffic policeman.

And then the final dagger, from a man whose name flirted with the edges of nominative determinism, Lampard taking a cut-back from Anelka and, first time, into his blindspot, swinging a shot across Reina and in off both posts, a breathtaking finish to end a breathless match. The first eight lots of 90 minutes between the two sides in this competition had provided just seven goals, the final 210 – extra-time in the 2008 semis and the two legs of this tie – had provided 15: a goal every 14 minutes. And there was still time for Essien to deny N’Gog with a diving-header clearance off the line, a particularly fitting end for a game that had gone through the looking-glass. Fittingly, the final whistle brought a burst of Madness’s “One Step Beyond” over the tannoy.

As the dust settled and the Madness subsided in West London, Liverpool caught a bus back to Anfield, hoping Manchester United might allow them back into the title race. On Saturday, another bus from London arrived in L4 0TH, this one from Islington, and Rafa’s masters of pragmatism duly thrashed out a second 4-4 draw in five days, Andrey Arshavin scoring all four for visitors Arsenal, Benayoun equalising at lights-out.

Chelsea’s Champions League semi-final with Barcelona, refereed by a Norwegian psychologist, Tom Henning Øvrebø, was another spicy affair. Øvrebø failed to respond positively to four penalty shouts from Chelsea, before a 93rd- minute strike from Andrés Iniesta, the blaugranas’ first shot on target, screamed inside the post to put Pep Guardiola’s team into the final against Manchester United. Drogba eschewed the diplomatic post-match platitudes and looked straight into the camera screaming, “It’s a fucking disgrace.”

As for Liverpool, the following three seasons would be among the worst in their modern history – seventh, sixth, then eighth (albeit with two domestic cup finals, beating Cardiff on penalties in February, losing to Chelsea in May) – as the riches and drama and cachet of the Champions League were temporarily confiscated.

After Rafa’s final-year unravelling, the Hodgson experiment, and a dabble with Dalglish, Liverpool switched American owners and the club’s next two managers would come with the shiniest of shiny white teeth and, the odd slip against Mourinho’s Chelsea aside, would put the smiles back on Liverpudlian faces. In fact, one of them would himself do a neat line in three-goal comebacks.

Scott Oliver is freelance writer who has two columns in Wisden Cricket Monthly and is a regular contributor to The Cricketer and ESPNcricinfo. He has written elsewhere about football for Mundial, ESPN and the Ringer, and about culture for the Guardian, VICE, i-D, the New European and others. @reverse_sweeper