Premiership, Anfield, Liverpool, 23 December 2001

This piece was written by Rob Smyth and featured in Issue 46

There’s no bad way to win a league title. It’s a uniquely rewarding achievement, nine months in the making, so anytime, anyplace, anywhere will do. But as any Arsenal fan will be generous enough to explain, that doesn’t mean all title- winning moments are equal.

In the modern era, Arsenal have won the league six times. By delirious coincidence, four of those titles were clinched away to one of their greatest rivals: twice at White Hart Lane, once at Old Trafford and once at Anfield, a game that also produced the most dramatic finish to a season in English football history. The other two, involving idyllic bank-holiday-weekend parties at Highbury, were pretty special too. But winning the league behind enemy lines is a fantasy that brings infinite glory, unimaginable euphoria and a healthy kick of schadenfreude. Most supporters don’t experience it once, never mind four times in 31 years. A handful of blessed souls were in the away end for all four games.

The story doesn’t end there. Spurs are their most hated rivals, Liverpool and Manchester United the other members of English football’s aristocracy. As well as winning the league, Arsenal have enjoyed coming-of-age victories away to all three. On each occasion, wins that felt giddily symbolic at the time were later confirmed as rites of passage for an emerging team.

David Rocastle’s orgiastic injury-time winner at White Hart Lane in the Littlewoods Cup semi-final replay of 1987 was the symbolic start of George Graham’s reign at Arsenal; Marc Overmars’s winner at Old Trafford in 1998 is a similar landmark in the Arsène Wenger years. And on 23 December 2001, ten-man Arsenal ignored xenophobia, injustice, history and Europe’s deadliest snake to outclass their title rivals Liverpool at Anfield. It was the start of the Invincible era.

It’s not only history that is written by the victors. Winning brings another privilege – it allows you to rewrite the preceding defeats, make them part of the prologue. When Arsenal were mugged by Liverpool in the 2001 FA Cup final, with Michael Owen scoring two clinical late goals to turn a 1-0 deficit into a 2-1 victory, it was presented as definitive evidence of their lack of a killer instinct. Since winning the Double in 1998 they had finished as runners-up five times: three in the league and once apiece in the FA Cup and Uefa Cup.

Arsenal’s subsequent success gave them the right to reframe that FA Cup final defeat as a line in the sand. They were mad as hell and they weren’t gonna take finishing second anymore. What happened next makes their version hard to dispute, although it took a while for them to take effective action. The first half of the 2001-02 season was a melodrama in which Arsenal sent mixed messages to their own subconscious, never mind the rest of the football world. There were rousing victories, exquisite football – but also a number of humbling, ignominious or exasperating defeats, most notably a minor fiasco at home to Charlton in which they created umpteen chances and lost 4-2. On the day of the Liverpool game, writing in the Sunday Telegraph, Patrick Barclay described them as “a team that can make Jekyll and Hyde look like Tweedledum and Tweedledee”.

The task of understanding them became even more difficult when they started to contradict their own recent history. In December 2001 Arsenal were unbeaten away in the Premier League and a bit of a mess at home, the polar opposite of the previous two seasons. In Europe, they were irresistible at home and useless away. They played the purest football in England yet had the worst disciplinary record.

In November and early December they had three huge victories, which in hindsight were forerunners of the game at Anfield. They thrashed the champions Manchester United, who were flattered by a 3-1 defeat, came from 2-0 down at home to a decent Aston Villa to win 3-2 and then outclassed Juventus in the Champions League. And then they went and spoiled it all with a desperate 3-1 defeat at home to Newcastle. Ray Parlour was sent off and Thierry Henry had to be repeatedly restrained after the match as he attempted to drill down into the laws of the game with the referee Graham Poll.

Wenger’s biographer Xavier Rivoire later wrote that he privately conceded the title that night. It’s an intriguing but jarring comment. In an unusually open title race, Wenger was just about the only manager to say that his team could win the league. Even Sir Alex Ferguson wrote off Manchester United, at least in public, after an unthinkable run of five defeats in seven games.

United’s desperate start to what was going to be Ferguson’s last season gave the rest an unexpected chance. They were aiming for a record fourth consecutive championship, and most thought it would be a formality when they signed two of the world’s better players in Ruud van Nistelrooy and Juan Sebastián Verón. United had won the last two titles at a canter – by 18 points in 1999-2000 and by 10 in 2000-01. It would have been a lot more had they not lost the last three games after checking out early for their summer holidays. Not even the most optimistic United-phobe saw what was coming in the autumn of 2001. Those signings, the sale of Jaap Stam and purchase of Laurent Blanc, Ferguson’s obsession with Europe and his apparently imminent retirement sent United into free-fall.

It made for the most open title race since the inaugural Premier League season, certainly in the first half of the season, and a compelling tale of the unpredictable. Chelsea beat Liverpool who beat Newcastle who beat Leeds who beat Arsenal who beat Chelsea three days after the Liverpool game. And, apart from Leeds, all of them beat – and in most cases hammered – Manchester United.

Before Christmas, Liverpool, Leeds, Bolton, Everton and Newcastle all spent time at the top of the table. Newcastle went there with that 3-1 win at Arsenal, who themselves missed the chance to go top that night. Arsenal, who started the game brilliantly before unravelling in the second half, were slaughtered in the press for their indiscipline. Henry displayed a surfeit of va-va-voom when he put his fist through a window after the game. “You cannot ask your players to be 100% committed for 90 minutes,” said Wenger, “and then walk off with a smile on their faces after a 3-1 home defeat when you are pressing for the title.”

Parlour’s red card in the same game was the 39th in since Wenger took over at Arsenal in October 1996. Patrick Vieira and Lauren also had upcoming suspensions because of an accumulation of yellow cards, Vieira for the game at Anfield. In the early 2000s Arsenal had a contradictory status: they were the sanctimonious villains of the Premier League, a team who would only pose for their mugshot atop the moral high ground.

“If you judge any manager over four or five years and add up his red cards you will always get an impressive amount,” said Wenger, though that part of his argument didn’t stand up to scrutiny. In the same period, by way of comparison, their biggest rivals Liverpool (22) and Manchester United (21) had barely half as many.

The rest of his assessment had a bit more merit. “People try to stop us in ways that are not always regulation, and sometimes we over-react. But I don’t think anybody would disagree that we try to play football. We try to play a physical game, because I think that’s all part of an exciting spectacle. Our football is based on pace, movement and commitment, and sometimes we go a bit overboard on the third quality, but we never go into any game intending to kick somebody.”

The criticism of Arsenal was part of a broader moral panic about the behaviour of footballers in England, with the media finding the whiff of testosterone increasingly pungent. External testosterone, anyway. It’s long forgotten now but at the time it felt like a never- ending story. “[Football’s] decadence is the subject of a thousand talk shows,” wrote Oliver Holt in the Times. “Never since the Fever Pitch boom of the 1990s took hold has football’s renaissance seemed so perilously close to falling back into a dark age.”

It was panto season, but there wasn’t much family-friendly entertainment in the stories emerging from various Christmas parties. The West Ham defender Hayden Foxe changed the mood in the VIP lounge at the Soho nightclub Sugar Reef by unfurling his walloper and draining it across the bar, a relief for which he was relieved of two weeks’ wages. Afterwards, he was a model of contrition. “I wouldn’t go so far as saying I was pissing at the bar in front of a thousand people,” he said. “It was a discreet quiet little one.” Another West Ham player puked over tables and seats, and the group were encouraged to leave the nightclub via the back door.

Ipswich’s Titus Bramble had so many pints of Nytol Substitute that he passed out in a taxi. The driver was unable to wake him so dropped him at the police station instead. There were also allegations of sexual assault (Blackburn), punch-ups (Leicester), criminal damage (Leeds), assault (Oldham) and – will anyone think of the children – an afternoon drinking session (Manchester City).

In the same week, Leeds’s Jonathan Woodgate was found guilty of affray after an infamous street brawl in January 2000, and earlier in the 2001-02 season, the Chelsea quartet of John Terry, Frank Lampard, Eiður Guðjohnsen and Jody Morris were fined for drunkenly living life to the max, the day after 9/11, at a Heathrow hotel full of horrified American tourists.

The Premiership’s sponsors, Barclaycard, accepted a PR open goal – they announced that Liverpool v Arsenal would be the first game in which the Man of the Match received a trophy rather than a bottle of champagne.

Henry’s behaviour after the Newcastle game, described as a “bizarre war dance” in the Sunday Times, gave the media another reason to stroke their chin. It was his second post-match meltdown in a couple of months: after a Champions League defeat away to Panathinaikos he went looking for the referee and had to be pushed away by Wenger and a local policeman.

Arsenal were fuming with two decisions in particular: the second yellow card given to Parlour (the Newcastle captain Alan Shearer asked Poll not to send Parlour off) and a penalty for a perceived foul by Sol Campbell on Laurent Robert. The first decision was borderline, but the second looked a brilliant tackle by Campbell. The defeat was too much for Henry: he had to be repeatedly restrained by Gary Lewin, the physio, and Martin Keown among others. It turned out that one of the reasons for Henry’s meltdown was that he mistook Poll for Steve Dunn, the man who refereed the FA Cup final earlier in the year and did not punish Stéphane Henchoz for two handballs on the line. Poll was proud, ruddy-cheeked and a little plump; Dunn was… well, never mind.

“It’s not my job to control my players,” said Wenger. “I am not a policeman. Thierry felt injustice. He knows he overreacted, but he didn’t insult or touch the referee. Thierry’s was a human reaction, and that’s why we will defend him if there is an FA charge.”

Henry was eventually charged with misconduct and banned for three games. ‘Eventually’ is the operative word: with the FA disciplinary department still moving at 20th-century speed, the case was not heard until March.

Henry’s reaction, and Arsenal’s collapse against Newcastle, was seen as more evidence of their suspect temperament. “Another loss in front of the Kop tomorrow will add further fuel to the rumour that Arsenal simply don’t have the stomach for the title fight,” wrote Adam Withrington in the Independent.

It was not an isolated view. Even Robert Pires, interviewed in the Observer on the day of the game, lamented their lack of ruthlessness. “We have excellent players, a great team, and we want so much to play well, but there are times when we don’t kill a match,” he said. “It is something we need to rectify, because we dominate, then the opposition have something like a corner, free-kick, or deflection and suddenly they are level.”

This consensus about Arsenal’s flakiness looks peculiar with hindsight, not least because exhibit A – that FA Cup final against Liverpool – was a match they dominated completely and would have won but for outrageous misfortune and the merciless brilliance of Owen. It was probably born of residual prejudice against foreign players, even if in this case there was a thundering, unspoken contradiction. Arsenal’s core of foreign players – Vieira, Henry and Pires – were champions of Europe and the world.

The counter-argument is that all of Arsène Wenger’s title-winning teams at Arsenal, whether their core was French or British, had the capacity for dramatic swings in form – they could take shortcuts to greatness or fall off a cliff. And in December 2001, there was plenty of reason to doubt Arsenal’s ability to win the title. One of the biggest was their form away from home to their biggest rivals, especially in the north.

Their visit to Anfield in 2001 came a year to the day after they had been hammered 4-0 on the same ground. A couple of months after that they were humiliated 6-1 at Old Trafford. With the score 5-1 at half-time, Wenger lost it in the dressing room like never before. And their overall record at Anfield was wretched – they had drawn one and lost eight of their previous nine visits in all competitions, and hadn’t scored a league goal there since 1992. Few people gave them a chance of victory.

Liverpool, despite a slightly unfortunate 4-0 defeat at Chelsea the previous weekend, were serious title challengers for the first time since Gérard Houllier took over in 1998. He was still recuperating after suffering an aortic dissection during the match against Leeds in October, with Phil Thompson in charge. Houllier, who came close to death, was absent from the touchline until a perfectly timed return in March helped them beat Roma to reach the quarter-finals of the Champions League.

In December, the Premier League was the priority. They knew a two-goal win over Arsenal would lift them above the leaders Newcastle, who had won 4-3 at third-placed Leeds the previous day. Arsenal started the game in fifth, though the table was so tight – only six points separated second and eighth – that a win would move them above Liverpool and into second.

There was a shadow over the game – a suddenly resurgent Manchester United. It was barely a fortnight since they were ninth in the table and Ferguson was writing off their title chances. They had only won three games in the league since them, all against relatively weak opposition, but a combined score of 12-1 and multiple slip-ups elsewhere made the rest of the league hear the Jaws score in their subconscious.

Six days before the Arsenal game, and three days after his 22nd birthday, Michael Owen won the Ballon d’Or. He finished ahead of Raúl, Oliver Kahn and David Beckham, and is still the only British winner since Kevin Keegan in 1979, though Kenny Dalglish (1983), Gary Lineker (1986), David Beckham (1999) and Frank Lampard (2005) have all been runners-up.

Owen had scored 36 goals for club and country in 2001, an eye-catching amount in a pre-Messaldowski world, especially for a player who didn’t take many penalties. (He took two in 2001, missing against Roma and scoring against Everton.) But the award was as much about the quality of his goals – in this case the significance – as the quantity. The standouts were his hat-trick in Germany for England and the two deadly finishes that shattered Arsenal in the FA Cup final; he also scored crucially against Roma, Porto, Bayern Munich, Everton and Manchester United. And he specialised in scoring the opening goal of the game, a priceless virtue in a pragmatic Liverpool team that was designed to get in front and shut up shop.

He missed the Chelsea game the previous weekend with a hamstring injury and, though his absence had little to do with the four goals Liverpool conceded, it reinforced his importance – especially as Liverpool missed enough chances to draw 4-4.

Liverpool attempted to address their over-reliance on Owen by signing Nicolas Anelka, who was becoming a journeyman at the age of 22, on loan from Paris Saint-Germain. The deal was finalised too late for him to play against his old club.

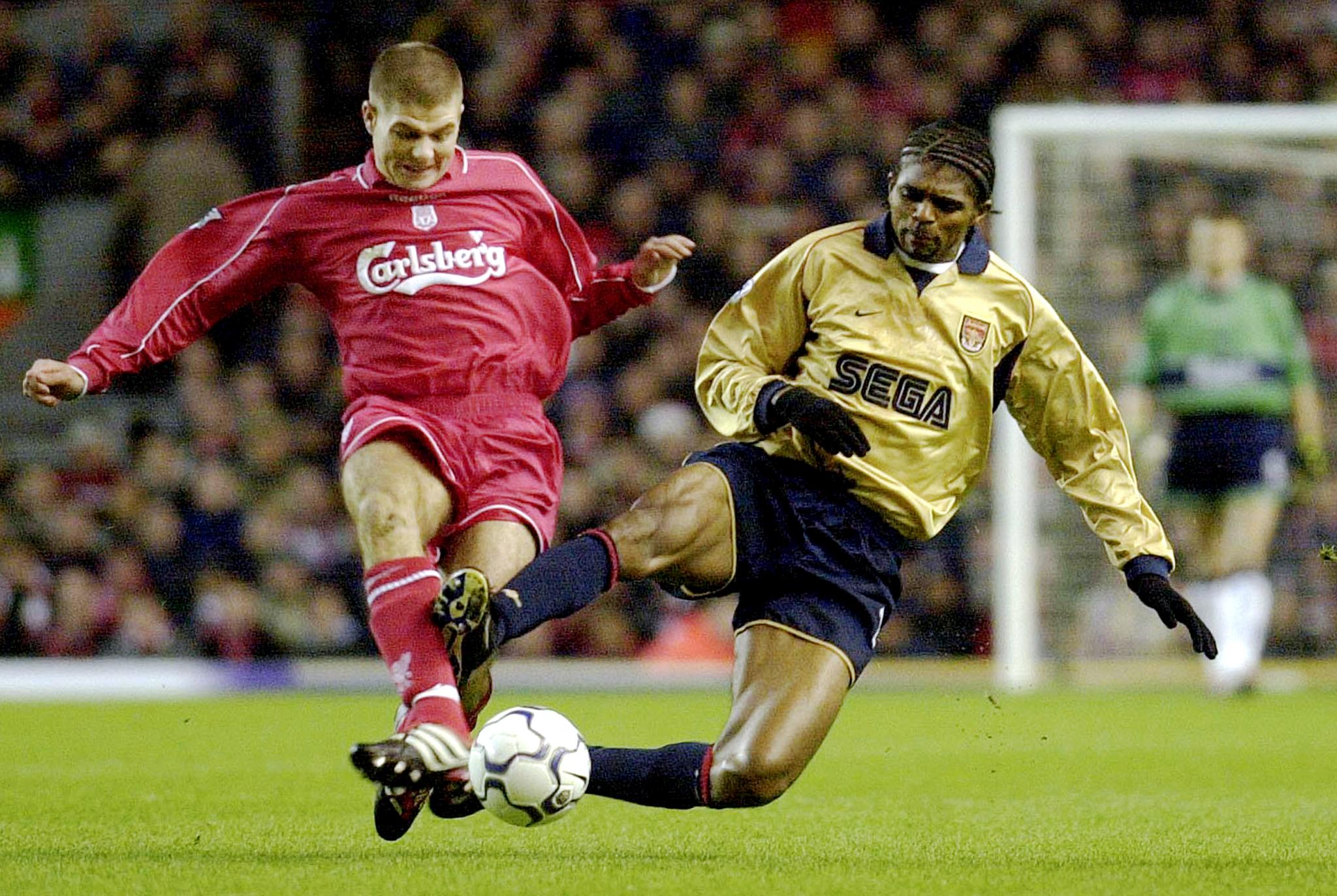

Owen was fit to return anyway, but Liverpool were without the quietly essential Dietmar Hamann through suspension. A month earlier, when Hamann was again suspended for a big game at Anfield, a midfield of Steven Gerrard and Gary McAllister were passed to death by Barcelona. This time Thompson and Houllier, who was helping to pick the team from afar, used Gerrard as the holding midfielder in a 4-1-3-2 system. Patrik Berger returned from a calf problem on the left of a narrow midfield that also included McAllister and Danny Murphy.

Gilles Grimandi, Vieira’s likely replacement in the Arsenal midfield, was injured in a reserve game on the Thursday, so Giovanni van Bronckhorst, a summer signing from Rangers, started instead. The other change was on the right wing, where the in-form Fredrik Ljungberg had recovered from a back injury and replaced Sylvain Wiltord. Although another summer addition, Richard Wright, was again available, Wenger stuck with his third-choice keeper Stuart Taylor. A toe injury meant Dennis Bergkamp was not available, though he would only have been on the bench; at that stage Kanu was the preferred No 10. Arsenal’s system was described at the time as 4-4-1-1 or even 4-4-2, though essentially it was what we now recognise as 4-2-3-1. In the absence of Vieira and the injured Tony Adams, Keown captained Arsenal and performed his duties with phenomenal gravity.

Liverpool were a tough, streetwise team, not always great to watch – the antonym of Arsenal, or at least the perception of Arsenal, so it was compulsory to talk about a clash of styles during the build- up. “We go forward more, they have a more cautious method,” said Wenger. “They are stable defensively, and they suck you in and have a snake up front to bite you. That’s what makes them dangerous. Ninety per cent of the time that snake is Michael Owen.”

There was even a clash of dress code. On an icy day in Merseyside, six of Arsenal’s outfield players wore gloves; no Liverpool players did so. The sextet were Henry, Pires, Van Bronckhorst, Ljungberg, Lauren and Kanu. It was a surprise they weren’t charged with bringing English football into disrepute.

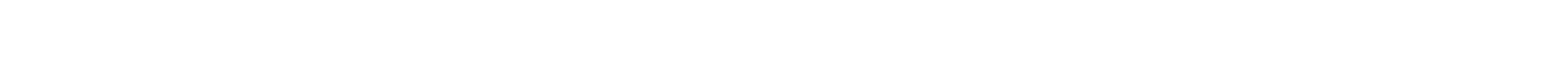

It took only 14 seconds for Arsenal to threaten, when a dangerous cross from Henry was sliced nervously over his own bar by the Liverpool right-back Jamie Carragher. His opposite number, Lauren, was booked in the third minute for a late tackle on Gerrard. That challenge reflected a pace of play, especially in the first 15 minutes, that looks furious even by modern standards. The two goalkeepers were dragged into a high- octane scrap – Jerzy Dudek kicked nervously when he could have picked the ball up, then Taylor spilled a swirling long throw and was grateful to see Campbell clear the loose ball.

Dudek might have been playing in goal for Arsenal. The previous summer he met Wenger and agreed terms, only for his club Feyenoord reportedly to ask for a prohibitive £10m. Arsenal signed Wright from Ipswich instead.

Dudek eventually joined Liverpool on transfer deadline day for a reported fee of £4.9m, when Houllier responded to a match-losing error by Sander Westerveld at Bolton by signing two keepers, Dudek and the promising Chris Kirkland from Coventry.

Arsenal were almost bitten when Owen, put through on goal by McAllister, was flagged offside. It was exceedingly tight, impossible to tell conclusively with the technology of 2001, just another little sliding door in English football history. Most of the quality came at the other end, where Gerrard – a willing if ill- disciplined presence in front of the back four – had to put out a number of fires. Anfield feels like a tight pitch at the best of times; with Liverpool employing a narrow midfield and the full-backs on both sides rarely getting forward, it was even more congested than usual. But within those ever-shifting phone- boxes, Arsenal played with precision and dizzying speed.

They also tried to maximise the larger spaces available on the counter-attack. Henry was caught offside a few times, such was his eagerness to run behind Sami Hyypiä and Henchoz, and Kanu missed a good chance in the 17th minute after an excellent break. Van Bronckhorst and Kanu covered 60 yards with two simple but penetrative passes, the latter out to Pires on the left. He slipped Gerrard adroitly and played a sharp square pass to Kanu, backing up the play just inside the area. Kanu allowed the ball to run across his body but sliced a sidefoot shot well wide. While Kanu was probably put off by McAllister lunging unsuccessfully at the ball just before it reached him, it remained an excellent opportunity.

At that stage Liverpool were more dangerous from set-pieces; three minutes after Kanu’s chance, McAllister clipped a free-kick onto the roof of the net. As the first half developed, Liverpool started to pin Arsenal back, often through a series of long throws. After 27 minutes, a graphic showed that 32% of the game had been played in Arsenal’s third as against 15% in Liverpool’s. The game felt closer than that, perhaps because Arsenal were so seductive when they did get into the final third. Either way, Liverpool came the closest to scoring in the 24th minute when Ashley Cole cleared off the line from… himself.

Dudek’s long punt was won in the air by Emile Heskey and reached Murphy 25 yards from goal. He stabbed a subtle through ball inside Lauren to find Owen on the left side of the area. Owen flicked a shot across Taylor that would have gone wide of the far post – although nobody realised that at the time, least of all Cole. He ran towards his own line, past Owen’s shot, and instinctively tried to poke it away with his left foot. But because he was so far off balance, Cole screwed the ball back towards his own goal. Somehow, in the same movement, he adjusted his body to clear the ball off the line with a tendon-busting twist of his right foot. His body was contorted in such an unusual way that it looked like he was playing a game of Twister. The ball hit Keown, who was busying himself in the six-yard box, and fell kindly for Lauren to clear.

It was a spectacular piece of instinctive defending from Cole, and the assistant referee decided the ball hadn’t crossed the line. In 2001 the only available goalline technology was the human eye, so it’s impossible to quantify Cole’s clearance in the same way that we talk about John Stones’s 1.12 centimetres in 2018-19. To the naked eye, it looks comparable.

Owen certainly thought so; he had already wheeled away in celebration of his 100th Liverpool goal. He was wrong on two counts. Even if the ball had gone in, it would have been an own goal by Cole.

While there was a necessary desperation in Cole’s clearance, the rest of his performance was a study in calm authority. And the eye-catching effectiveness of his goalline intervention reinforced a rapidly growing feeling that Arsenal and England had stumbled upon a serious talent. Cole turned 21 three days earlier, but he had already come of age during a life-changing year. At the start of 2001 Cole was uncapped for England and had started only four Premier League games for Arsenal. By the end he was undisputed first choice for club and country. His talent was so obvious that Wenger felt safe to sell the excellent Silvinho – who was in the PFA Team of the Year the previous season – to Celta Vigo in the summer of 2001.

Owen’s errant finish meant there had still been no shots on target, though the intensity and quality meant it never felt a dull game. There would have been an effort on target had Keown not inadvertently deflected Pires’s rasping snapshot wide of goal after a free-kick was half-cleared. It was only 16 months since Pires sat on the bench at Sunderland, in the first match of the 2000-01 season, and wondered what the hell he had let himself in for by coming to English football. But he acclimatised during an ultimately promising first season and now, halfway through the second, did not look remotely intimidated by the physicality of English football. He barely looked cognisant of it. At Anfield his direct opponents were Carragher and Gerrard, two unsentimental young players who had already shown an ability to bully weaker opponents, yet Pires demanded the ball in tight areas at every opportunity.

There were times when it looked like he wanted to take the piss out of them. In the 33rd minute, Gerrard hared across to challenge Pires, who could have avoided confrontation by playing a simple pass to the unmarked Cole. Instead he stopped the ball dead, seducing Gerrard to tackle him, before dragging it away and being fouled.

In the first half, Pires and to a lesser extent Kanu played with a freedom and serenity that stood out in such a helter- skelter game. Occasionally they were too relaxed – like when a dodgy crossfield pass from Pires was intercepted by John- Arne Riise, who ran 60 yards down the left before being relieved of possession by the diligent Parlour. Parlour had even more covering to do when, in the 36th minute, his midfield partner was sent off.

The Premier League can’t resist a moral panic. If it comes with its own maze, even better. Most seasons there is either an attempt to clamp down on a particular offence or a mess created by evolving interpretation of the laws. In 1990-91 it was the professional foul; in 2003-04 passive offsides; and in 2001-02, on the field at least, football’s greatest evil was diving. At the start of the season, the referee Graham Poll said players who dived should be given a straight red card. While that draconian punishment was not implemented, there was a clampdown, which led to some players being sent off after receiving a second yellow card for diving.

Attitudes towards diving hardened when a number of red cards were rescinded because video evidence showed the offences had been exaggerated. Earlier in December the problem was discussed at a refereeing seminar at the Staverton Park Hotel & Golf Club in Daventry, Northamptonshire, with instructions given to book more players for simulation. “We may get one or two wrong,” said Poll, “but that may be the only way to eradicate it.”

This is the context in which Van Bronckhorst was sent off. He’d been booked after 20 minutes for cleaning out Hyypiä – his fifth yellow card of the season, which made him the latest Arsenal player due for a suspension. “Now he’s got to stay on his feet,” said Andy Gray, the Sky Sports co- commentator. “That’s the thing about the modern game now, if you get an early booking like Van Bronckhorst or Lauren, any time – any time – they go to ground in a tackle, they are really risking a second yellow card.”

He was right about everything except the tackle. Van Bronckhorst got a second yellow card for going to the ground just inside the Liverpool area when Hyypiä tried to ease him off the ball. By the time Van Bronckhorst got to his feet, the referee Paul Durkin was already on the scene, yellow card proudly in hand. Those who thought Van Bronckhorst was harshly treated – and it was a sizeable majority – pointed out that he hadn’t even appealed for a penalty. But this was effectively inadmissible evidence: Durkin had made his decision before Van Bronckhorst got to his feet. Even so, the consensus was that Van Bronckhorst was collateral damage in the ongoing moral panic, and that Durkin couldn’t get his card out fast enough.

Van Bronckhorst was wearing moulded studs, a peculiar decision on a frosty pitch but one that supported the view he had simply slipped. On Sky Sports, Gray described it as “disgraceful… ridiculous”. In the Sky studio, for the second time in a week, Alan Shearer suggested an Arsenal player had been wrongly sent off.

After the game, Wenger thought Durkin had forgotten he had already booked Van Bronckhorst, though Durkin later said that wasn’t the case. A couple of years later, after a televised draw between Manchester United and Newcastle United, Durkin gave a post- match interview in which he admitted he should have given Newcastle a penalty. On this occasion, he was not for turning. “I had a really good view of it and I thought he was trying to deceive me,” he said. “Diving is a major problem in the game and it’s got to be eradicated. I was 100% sure.”

Two decades later, we have a greater appreciation of the levels of subtlety that can be involved in diving, and it’s not beyond the realms that Van Bronckhorst was trying to con the referee. He had overrun the ball, which is often when a footballer’s instinct to visit the canvas kicks in. It’s possible that he dived and then, in the split second before he got to his feet, realised that he could be in trouble and made a point not to appeal for a penalty. One thing that supports this interpretation is his lack of outrage at the decision, though that may simply have been a combination of sheepishness and shock. His teammate Henry started laughing, as if to convey that the vendetta against Arsenal had officially gone beyond satire.

They were almost universally slaughtered for their behaviour after the Newcastle game, but on this occasion most people sided with them. “You see the problem,” wrote the Telegraph’s Paul Hayward after the game. “It’s one of intent, of motivation, which only the one in the dock can solve… One of modern football’s problems it that every decision is made in a cauldron, where nobody is ever wrong, one side is always being victimised and the survival instinct mutates into rampant self-interest. In this climate, referees can only arrive at an instant verdict and wait for the incoming barrage of dismissive comment from every source.”

And that was in 2001.

The societal quest for clarity was not helped by defenders often accusing people of diving when they had palpably fouled them. The previous day, Leicester’s Matt Elliott lost it with Joe Cole when West Ham were given a penalty at Filbert Street. Replays showed a clear and obvious foul by Elliott on Cole, but Elliott was in such a lather of outrage that he manhandled Cole, then stuck the head of Trevor Sinclair and was sent off.

Van Bronckhorst’s red card was Arsenal’s 40th under Wenger in just over five years. There was an upside to that dubious record – they were so familiar with being a man down that there was no reason to panic when it happened again, especially as their record in such circumstances was phenomenal. The previous 39 red cards had come in 38 games (they managed two for the price of one at White Hart Lane in 1999-2000), in which their record was W18 D8 L12.

Parlour, now the lone central midfielder, walked over to suggest a temporary rejig until half-time. With Wenger shaking his head and effing and jeffing under his breath, it looked like Parlour was telling him what to do rather than the other way round.

Arsenal were already short in midfield. Vieira was suspended, Grimandi injured and Lauren had been repurposed at right-back. They had Edu on the bench, though he had barely played after his delayed arrival at Arsenal because of passport problems. Oleh Luzhny could have come on at right- back, with Lauren moving back into midfield. Pires could have moved into the centre, where he started the season with Arsenal after winning the Golden Ball at the Confederations Cup in the same position.

Instead, the management team of Parlour and Wenger decided to pull Kanu back into central midfield. Even allowing for Kanu’s Total Football education at Ajax, it was quite a leap of faith. There was one encouraging precedent: at the Nou Camp in 1999- 2000, Kanu spent the last 10 minutes in central midfield after Grimandi was sent off for elbowing Pep Guardiola, who ensured justice was administered with a Sergio Busquets-style peek as he rolled around. In that time, Kanu even scored Arsenal’s equaliser.

The switch meant Arsenal’s attacking shape was effectively a pentagon: Parlour and Kanu at the base, Pires and Ljungberg wide and Henry on his own up front. They responded to the red card by playing as if nothing had happened. If anything, the pace became even faster in the ten minutes between Van Bronckhorst’s red card and half- time. And in that time, their emergency central midfielder Kanu created the opening goal.

He wandered over to the left to receive a pass from Cole, then darted infield and ignored a couple of challenges. Henry borrowed the ball for a few seconds, turning elegantly away from McAllister before giving it back to Kanu. He allowed the ball to run across his body and threaded a clever first-time through pass to Ljungberg, who made a typical run infield from the right. Ljungberg touched the ball past Dudek and waited to be flattened. It was a clear penalty, and there was an assumption that Dudek would also receive a red card for denying a clear goalscoring opportunity. In fact he wasn’t even booked, with the referee Durkin later explaining that it was “a careless rather than reckless challenge”.

Henry tucked away the penalty with authority, sidefooting it low to the left. It was his 16th league goal of the season, which put him comfortably ahead of Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink (13), Michael Ricketts and Ruud van Nistelrooy (both 10) in the race for the Golden Boot. Owen had nine. Thompson, Liverpool’s interim manager, attempted to introduce more wit to his side’s play with a double substitution at half-time: Vladimír Šmicer and Jari Litmanen came on for Heskey, who had an ankle injury, and McAllister. It meant Gerrard was even more isolated, almost a one-man midfield. Against a team as slick and creative as Arsenal, even down to 10 men, Liverpool’s shape was asking for trouble.

But so, at times, was Arsenal’s approach. The line between self-expression and collective harm can be gossamer thin, and Pires and Kanu walked it a few times. In the 49th minute, Pires, who had come back for a corner, cushioned a risky pass back towards the edge of his own area. It was intercepted by Owen, who slithered away from Campbell and Keown only to slice wide with his left foot.

Three minutes later Henry missed an even better chance on the break. Parlour and Ljungberg harassed Šmicer into conceding possession 15 yards inside the Arsenal half, and then Parlour pushed the ball infield to Pires, unmarked in the centre circle. He moved into the space, angling his run slightly to the left so that Henry could move in the other direction. They couldn’t have synchronised their criss-cross movement any better had they been rehearsing it for a week.

When the time was right Pires stabbed a sudden pass through to Henry, who darted into a surprisingly big gap between Henchoz and Hyypiä. Henry controlled the ball on the run, on the edge of the D, and in the same movement tried the kind of out-to-in curler that later became his trademark. On this occasion his bearings weren’t quite right and the ball went a few yards wide. It felt like it a costly miss, another demonstration of Arsenal’s lack of killer instinct. But only for 27 seconds.

That’s how long it took for Pires to make a glorious second goal for Ljungberg. It developed too fast for the TV director – by the time he had stopped showing replays of Henry’s chance, Pires had the ball again, this time on the left wing. He had intercepted a long pass from Gerrard, who, with the right-back Carragher out of the game, charged across in an attempt to redeem his error.

What happened next is part of Arsenal folklore. Pires needed only four touches to twist Gerrard inside out, not once but twice. On both occasions he pushed the ball infield towards Gerrard, who thought he could win the ball and was quickly disabused of the notion.

The first time Pires tricked Gerrard, he did not quite create enough space to get away, so he did it again. Pires slowed down deliberately, and showed Gerrard the ball. As Gerrard lunged at it with misplaced optimism, Pires dragged it down the line a second time, unbalancing Gerrard to such an extent that he was completely out of the game. In that precise moment, he would have struggled to recite his full name.

All the while, on the other side of the field, Ljungberg was charging full pelt from the halfway line, just in case Pires got away from Gerrard. Throughout football history, a gazillion such runs had gone unrewarded; this was a reminder why people kept making them. Hyypiä, standing near the penalty spot, spotted Ljungberg over his left shoulder. Too late: he was static and Ljungberg had the run on him. Pires screwed a precise low cross to the near post, which Ljungberg clipped gleefully past Dudek from six yards. (He scored an eerily similar goal in the return fixture three weeks later, a 1-1 draw at Highbury.)

Ljungberg ran straight towards the front row of the away end to celebrate and then made a point of acknowledging Pires’s part. “Well, this is awesome from Arsenal!” said the Sky commentator Martin Tyler. He was referring not only to the goal, brilliant though it was, but also the few minutes either side of half- time, in which Arsenal had responded to extreme adversity by aiming for the stars. Tyler’s commentary endured, not just for its easy quotability but what it said about Wenger’s second great Arsenal side: over the next few years, their football frequently inspired awe.

In the face of some serious competition, Pires and Ljungberg were the symbols of Arsenal’s 2001-02 season. They were also a glimpse of the future. In those days it was still unusual to see inverted wingers in English football. Ryan Giggs, David Beckham, Damien Duff, Harry Kewell, Laurent Robert, Norbert Solano all played on their natural side virtually every week.

At Arsenal, they took pride in doing things differently, and their left-winger Pires barely used his left foot. Ljungberg was slightly different – though relatively two-footed, he was essentially playing on his natural side, as a right-footer on the right wing. Yet chalk was rarely found on his boots. Whichever wing Ljungberg started on, he did his best work when he came infield, never more dangerously than when he ran onto sliderule passes or crosses from Pires, Henry or Bergkamp. The latter was a portmanteau lover’s dream, especially when #Ljungbergkamp produced multiple goals during the 2001-02 run-in.

If Ljungberg was a space invader, who did a lot of his best work without the ball, then Pires was all about touch and feel. He had the rare ability to play high-level sport with a resting heart rate; the closer to goal he got, the more serene and sensual he became. For Arsenal fans, watching Pires in the final third was the football equivalent of a tantric massage. Pires went on to win the FWA Footballer of the Year award, though the greatest season of his life will always have a bittersweet tang: a cruciate ligament injury meant he missed the run-in and also the World Cup.

Though their styles were different, Pires and Ljungberg had one big thing in common – both seriously doubted they would ever be able to adapt to the physicality of English football. “It took a while,” said Ljungberg. “In my first game, I was shocked at how you kick people around here.”

This was Ljungberg’s fourth season and Pires’s second, and both had learned that they could thrive, never mind survive, without compromising the things that made Wenger buy them in the first place. When he joined Arsenal, Pires, approaching his 27th birthday, had lost his way at Marseille. One of Wenger’s greatest strengths, particularly in his first decade as Arsenal manager, was his ability to empower his team to express and even enjoy themselves on the field. At the turn of the century, footballers playing in England were expected to do many things on the field. Having fun was not one of them.

Arsenal deserved a few minutes to bask in the glory of their second goal, but such luxury is rarely on offer at Anfield. Dramatic Liverpool comebacks have been in the brochure for decades, and visiting teams are rarely comfortable even when they are ahead. Within 157 seconds of Ljungberg’s goal, Litmanen scored to spark an onslaught that briefly threatened to overwhelm Arsenal.

The goal stemmed for a throw-in that should have been awarded to Arsenal, although nobody really complained. Riise took the throw, got it back and dumped a routine cross into the middle. It bounced beyond the far post to Owen, whose woefully mishit half-volley turned into a perfect cross for Litmanen. He headed in from a couple of yards.

For the following five minutes, Arsenal barely got out of their quarter, never mind their half, and an equaliser felt inevitable. But they held on grimly until an accomplished piece of play from Parlour changed the mood. He collected a loose ball in the D, walked past Riise and won a throw-in off Berger. It doesn’t sound much but it was the first bit of composure by an Arsenal player since Litmanen’s goal, akin to a batsman sending a message to the dressing room by defending confidently on a dodgy pitch.

Though he had revelatory support from Kanu, Parlour still had to do the bulk of the work in midfield, and gave the sort of performance that made him such a magnet for the word ‘underrated’. Parlour’s cross-country abilities were highlighted whenever he had a good game, and he needed them more than ever with Arsenal down to 10 men, but such a limited focus belies the authority and composure that he added to his game under Wenger.

At one point, as if to emphasise he was doing the work of two men, Parlour even fouled Riise and Berger simultaneously. “Since Ray Parlour performed like 21⁄2 men for the 96 minutes the match lasted it was easy to forget the disparity in numbers,” wrote David Lacey in the Guardian. “With Sven-Göran Eriksson in the crowd Parlour almost completely upstaged Steven Gerrard, who will be the fulcrum of England’s team in the World Cup, in a memorable display of industry and ingenuity.”

The path to greatness is usually rocky, and Gerrard – still only 21 – was in the middle of one of the more trying seasons of his career. He made unwelcome headlines in the autumn, first after being sent off for a vile tackle on George Boateng and then when a quiet drink, six days before England’s World Cup qualifier against Greece, was sensationalised by the press. “Debating player behaviour was all the rage at the time,” said Gerrard in his first autobiography. “I was being used for target practice.”

He scored only four goals in 45 games, struggled with a recurring groin injury and was embarrassingly outwitted at times, most notably by Pires here and Michael Ballack when Liverpool lost a Champions League quarter-final to Bayer Leverkusen. Gerrard, who had won the PFA Young Player of the Year award the previous season, finished third this time behind Newcastle’s Craig Bellamy and Bolton’s Michael Ricketts.

Nobody of sound mind doubted that they were anything other than growing pains, and there were still plenty of demonstrations of his spectacular talent. Either side of that horror tackle on Boateng, he scored majestic goals in wins away to Germany and Everton. And in a three-week period at the start of the year he created goals against title rivals at Highbury, Old Trafford and Elland Road with outstanding, subtle passes that were more avant-garde than Hollywood.

That groin injury meant Gerrard was not England’s fulcrum at the World Cup – but nor was Parlour, even though he ended the season spectacularly. Parlour scored the opening goal when Arsenal beat Chelsea 2-0 in the FA Cup final, celebrated with a two-day bender and then produced a Man of the Match performance when Arsenal won the league at Old Trafford four days later. Parlour won the last of his 10 caps in November 2000, made a couple of Eriksson’s early squads and was never seen again. At the time it was only Ray Parlour, so nobody said much. In hindsight it’s hard to fathom that he wasn’t a regular squad member, especially when you consider some of those who played in central midfield in Eriksson’s early years: Carragher, Murphy, Gavin McCann, David Dunn. All were fine players; none were as good as Parlour in that position at that time.

Parlour’s unlikely midfield partner, Kanu, also helped Arsenal take the sting out of the game on a number of occasions. He was put on the graveyard shift at short notice and decided to make a musical out of it.

He routinely ignored the intensity of the game, bringing a testimonial playfulness to proceedings. A backflick nutmeg on Gerrard prompted the Sky co-commentator Andy Gray to burst out laughing, and later in the game he sent Gerrard running towards the wrong fire with a delightful flick over his head. But as with Pires, Kanu walked the line between hero and eejit. A loose pass in the 61st minute eventually led to Šmicer having a shot blocked by the increasingly immense Campbell.

Kanu being seconded to midfield was another example of Arsenal’s capacity to make do and mend. At Anfield they were without seven senior players – eight once Van Bronckhorst was sent off – and they had so many injuries and suspensions throughout the season that they needed every squad member. Their injury list would have derailed most seasons, and they didn’t receive nearly enough credit for the way they handled it.

Even players who had been ridiculed and written off, like Luzhny and Igors Stepanovs, played an important part. Arsenal also needed three goalkeepers – Seaman, Wright and Taylor all received championship medals after playing at least 10 games each. (Taylor, who played nine of the first 37 league games, came on as a late substitute for Wright in the last game, a title celebration at home to Everton.)

Berger missed an excellent chance in the 65th minute after sublime play from Litmanen, who dummied Parlour near the halfway line and then opened Arsenal up with a forensic through pass, but Liverpool’s chances were isolated incidents rather than manifestations on an ongoing storm. The five-minute period after the Litmanen goal was the only time that Arsenal were under siege, and Liverpool became increasingly desperate as the second half developed. Berger had multiple long-range shots, most of them hopeless. And on at least four occasions in the second half, Henchoz, Hyypiä or Riise lumped a long ball straight out of play. It was as if they hadn’t registered that Šmicer and Litmanen were on the field and that Heskey was not.

Arsenal maximised their physical advantage by defending narrowly and inviting crosses, most of which were cleared without a second thought by Keown and Campbell. They did the same job with opposing faces: Keown defended with frenzied concentration, Campbell with calm control. It took him a while to settle down at Highbury – he arrived overweight and was then injured – but his admirable performance in a vicious atmosphere at White Hart Lane a month earlier was effectively the start of his Arsenal career. By the time they went to Anfield he was looking like one of the world’s best defenders. To reinforce the point that he was up and running, three days later he scored his first goal for the club in a 2-1 win over Chelsea.

The win at Anfield was a triumph for Campbell and the defence, yet what really defined it was the optimism and self-belief of Arsenal’s football after they went down to 10 men. They showed that defiance doesn’t have to mean defence. Even in the last half hour, when it would have been natural to sit on their lead, they could not resist expressing themselves in attack. Henry missed an opportunity in the 61st minute when he found himself one v one with Hyypiä, a situation that gave any Premier League defender the heebie-jeebies, only to inexplicably overrun the ball. Then, in the 77th minute, he flashed a diving header over the bar after a long passing move.

The match was a study in nuance. Arsenal looked a class apart in their creativity, yet Liverpool still created some excellent chances to equalise. In the 73rd minute, Berger’s shot deflected just wide off the indefatigable Ljungberg; then, six minutes from the end, Murphy’s mishit volley bounced over the stretching Owen in front of goal. At the time Owen looked well offside. Replays showed he was not.

At no stage did Liverpool push Gerrard further forward so that he could impose his elemental force in the final third. That looks absurd now, though nobody really commented on it at the time. In the winter of 2001, Gerrard was compared, at least tentatively, to Roy Keane and Patrick Vieira rather than Paul Scholes and Frank Lampard. “I don’t see the similarity,” said Gerrard, but at that stage he was in a minority. Even when Hamann was available, Gerrard often played alongside him.

It was only in the last five minutes of normal time that Wenger gave up on trying to score a third goal. He brought on Matthew Upson for Pires, then Luzhny for Kanu. That led to the slightly peculiar sight of Luzhny lumbering around in midfield and Upson running up and mainly down the left wing. Even then, Arsenal couldn’t help themselves – they almost scored a third in injury time when Upson drove wide from 20 yards after a superb break involving Ljungberg, Parlour and the other substitute, Sylvain Wiltord.

By that stage Ljungberg was shattered, though he still had enough puff to get a yellow card for excessive use of the mouth in injury time. Taylor was also booked for time-wasting. Liverpool’s last opportunity from open play came just before that, in the 90th minute, when Berger flicked a header onto the roof of the net from Carragher’s cross. It was his sixth attempt at goal, none of which were on target. Riise then blasted a free-kick wide in injury time.

When Liverpool won a corner moments later, Hyypiä made one last attempt to unsettle his marker Keown. As they waited for the corner to be taken he pointedly leaned towards Keown, staring intently at him while sticking his tongue out. It was on the weird side of desperate. Keown, the concept of tunnel vision in human form, didn’t flinch. He may not even have noticed.

At the final whistle his defensive partner Campbell bounced around, celebrating the kind of hard-earned, potentially season-shaping win for which he came to Arsenal. Then the whole team went over to the away supporters, whose long journey home suddenly seemed full of Christmas possibility. “It’s hard to convey the climactic euphoria of such an ‘against all odds’ conquest,” wrote Bernard Azulay in his season diary, Arsenal on the Double. “To appreciate it fully, one has to have schlepped to Spain to be defeated by Deportivo, or to Blackburn for the second string to slump 4-0 in an insignificant cup sortie. Such hardships are the dues we endure, in order to truly savour the unadulterated high of Sunday’s celebrations. That sense of oneness with those players who came over at the final whistle to share a few moments of mutual respect and in whose expressions of delight you see your own ecstasy reflected.”

The result continued Arsenal’s excellent form away from home: at that stage, 22 of their 33 league points had been collected on the road. Even in December, it was a talking point that they were still unbeaten away from home. Nobody – not even, at that stage, Wenger – imagined they could go a whole season unbeaten away from home, never mind a whole season unbeaten full stop.

“Their victory set new standards of excellence in this season of uncertainty and upheaval…” wrote Oliver Holt in the Times. “Arsenal’s layers of brilliance suggested they will soon emerge as the most durable and classy of the contenders scrapping so desperately for Manchester United’s crown.”

Wenger said later that the Anfield result convinced him they would win the league. It was the day when Arsenal revealed mental reserves that few knew they had. Perhaps even they didn’t know. The wins over United, Villa and Juventus were valuable but they were all at Highbury. For symbolism and self-belief, nothing beats a hard-fought victory away from home – especially, given the attitude towards this particular Arsenal side, if it’s up north.

Anfield 2001 is the kind of game that forms new pathways in the brain, and broadens both ambition and expectation. The fact Arsenal did it without sacrificing their flair meant it had an even greater impact on their confidence. There is more than way to show character, and this was a fresh, new take on a staple of English football: the uncompromising victory away from home.

Games like this made Wenger even more intransigent, a defining strength that stealthily became a weakness as his judgement became less secure towards the end of his time at Arsenal. But those problems were a thing of the future.

There were times when it was grim up north for Invincible-era Arsenal, when they lost the league in 2002-03 and their aura in 2004-05, and every point dropped north of Watford Gap was seen as some kind of moral failing. But there were even more games like this, when they made a mockery of all the clichés and, crucially, won by playing their way. And they proved, beyond reasonable doubt, that there is no correlation between mental strength and whether you wear gloves on a cold day.

In December 2001, English football was a blank canvas. Manchester United were vulnerable for the first time in years, Ferguson was about to retire – or so we thought – and five other teams had the potential to usurp them and become the next big thing. From Anfield onwards, Arsenal stole a march on Liverpool, Leeds, Chelsea and Newcastle. When his team won at Highbury, Sir Bobby Robson responded to Arsenal’s meltdown by saying that “they should learn how to lose round here”.

Arsenal found a creative solution to the problem of being bad losers: they stopped losing. They were unbeaten for the rest of the season, at least domestically, and outsprinted Liverpool and Manchester United in a blistering title race. They won their last 11 games in the league and stormed to the Double, which they clinched with another famous victory at Old Trafford. And they didn’t lose a single game away from home, an apparently impossible achievement in such a bruisingly competitive, league. It planted a seed in Wenger’s mind. Two seasons later Arsenal saw that feat and raised it by being unbeatable at home and away.

The glories of May 2002 and May 2004 can be traced back to 23 December 2001. There have been plenty of false epochs down the years – Arsenal had one away to Liverpool in February 1973 – but this was the opposite. All the hope and possibility of that euphoric afternoon at Anfield was fulfilled, even exceeded. For Arsenal fans, it makes the memory of the game so much richer. Their victory was for life, not just for Christmas.

Rob Smyth is co-author of Danish Dynamite: The Story of Football’s Greatest Cult Team and And Gazza Misses The Final, a collection of minute-by-minute reports on classic World Cup matches.