Euro 2008 quarter-final, St Jakob-Park, Basel, 21 June 2008

Covering a classic from 16 years’ ago to this day, this is Michael Yokhin for issue 39

They hugged each other after the final whistle. They felt awkward. The two Dutch coaches looked at the stands of St Jakob Park which were almost exclusively filled with fans in orange shirts. Those supporters had been extremely optimistic just two hours previously, and Marco van Basten couldn’t avoid the feeling that he had let them down. His personal dream was over. His job was left unfinished. Guus Hiddink had instigated his downfall and deep inside the veteran shared the disappointment of his countrymen. And yet, he was proud too, because he was the worthy winner.

The Dutch press presented the game as a fight between the “two Netherlands”. Both teams had seemingly developed great momentum ahead of the Euro 2008 quarter-final and the “real” Oranje were considered clear favourites. However, Russia were the ones who represented the true Dutch spirit on the night. They should have won much more comfortably, and their performance was nothing short of spectacular. Hiddink’s game plan proved to be a masterpiece.

Was it really a surprise? Not if you take a more thorough look at the weeks, months and years that preceded what seemed to be a historic occasion.

We all know that football is an unpredictable game. At times, the whole scenario is hugely influenced by pure luck. One thing is certain, though – psychology can never be overestimated. Gradual development of healthy self- confidence is much likelier to bring success than overconfidence and false euphoria. Mental preparation is at least as crucial as tactical and physical aspects. Few games highlighted that better than the spectacle in Basel on 21 June 2008.

Even the date itself made the Dutch believe that they were destined to win, because they had never lost on June 21, achieving some brilliant results – including the 2-1 semi-final triumph over West Germany at Euro 88, when Van Basten himself scored a dramatic late winner in Hamburg. They lifted their only trophy that summer and the general feeling in the country was that the former striker was about to bring home the gold medals once again, this time as a coach.

They felt at home in Switzerland. Only 38,000 spectators could enter the stadium, but at least 150,000 Dutchmen were in Basel ahead of the game. Few of them had significant doubts. There was caution ahead of the tournament, following the tough draw that grouped the Netherlands with both of the 2006 World Cup finalists, but Van Basten’s side beat both of them in their opening fixtures in Bern, and became everyone’s darlings.

First they faced the world champions Italy and won 3-0, largely thanks to the opening strike by Ruud van Nistelrooy who looked miles offside but was actually in a legitimate position because Christian Panucci was lying off the pitch at the time. Shortly afterwards, Giovanni van Bronckhorst cleared off the line and immediately led a brilliant counter- attack, expertly finished by Wesley Sneijder. The left-back rounded off the win with a very rare header following another swift break.

Four days passed, and France were dismantled 4-1 at the same ground. Dirk Kuyt scored after a corner, Arjen Robben assisted Robin van Persie and netted himself from a tight angle, and then Sneijder put the icing on the cake with a world-class strike from distance. Seven goals in two matches – some of them of the highest quality – were enough to raise expectations beyond any reason.

Guus Hetterscheid, a Dutch journalist who went to Switzerland as a regular fan in 2008, said: “The team surprised all of us by beating Italy and France. Following those results, we expected them to go very far, and Russia were not seen as a major threat.” The most popular phrase was “Guus gaat naar huus” – “Guus [Hiddink] is going home”. In fact, fans became so optimistic that Van Basten decided to ban them from training sessions in Lausanne that were originally supposed to be open to the public. He didn’t want the supporters to make his squad over-confident, but even the coach himself smiled when a foreign reporter asked him: “How come all the players seem to like you so much?”

In reality, that was a bizarre thing to say, as two key players had refused to go to the tournament because of Van Basten. Clarence Seedorf, in his prime at AC Milan, stunned the country by announcing in May, “The right conditions have not been created to let me perform at my best and to excel effectively as the team member I always strive to be.” Personal problems with the coach were behind that decision, and that was also the case with Mark van Bommel who chose not to represent the team after the 2006 World Cup as long as Van Basten stayed in charge. Ruud van Nistelrooy followed him in January 2007, only to be persuaded to change his mind four months later.

Van Basten’s inability to find common language with numerous performers had led to serious criticism in the Netherlands for a long time, but that wasn’t even the major issue. The most significant problem was that the team failed to play decent attacking football and showed outright negativity on various occasions. Despite a high number of world-class forwards, the Dutch found it difficult to put the ball in the net and scored just 15 times in 12 Euro 2008 qualifiers.

Performances in a couple of 1-0 wins over Luxembourg were dire and qualification was anything but straightforward from a relatively comfortable group. The Netherlands finished second behind Romania and just a point ahead of Bulgaria. They made it largely thanks to a good defensive record and it seemed that keeping a clean sheet was much more important than scoring – a concept that went against the very core principles of Dutch football and was especially astonishing given Van Basten had been a great striker for teams managed by Johan Cruyff and Arrigo Sacchi.

Many fans were relieved when Van Basten refused to extend his contact with the Dutch football federation in February 2008, preferring to join Ajax in the summer instead. Memories of the disastrous 2006 World Cup campaign were still fresh in memory – that tournament ended in the last 16 when the Dutch lost 1-0 to Portugal in the infamous Battle of Nuremberg that featured a record 16 yellow and four red cards.

Khalid Boulahrouz played a major part in igniting the violence. The tough right- back was specifically instructed to hunt down Cristiano Ronaldo, managed to injure the winger in the first half and was eventually sent off after the break. “It was clearly an intentional foul,” Ronaldo claimed. The cynical plan was outrageous, and many in the Netherlands felt that technically limited players like Boulahrouz shouldn’t have been allowed to represent the country anyway. The defender made a lot of headlines again before Van Basten’s exit at Euro 2008, but for very different – and tragic – reasons.

Boulahrouz wasn’t supposed to make the final squad this time, but was called up as a late emergency replacement for the injured winger Ryan Babel. Van Basten’s decision was controversial in the first place, given the fact that the players’ positions were not directly comparable, but the defender went on to play in every match during the group stage, and performed well. Then, three days before the quarter-final clash, Boulahrouz’s wife gave birth prematurely and their daughter didn’t survive.

Instead of watching the crucial game between Russia and Sweden that decided his opponents in the quarter-final, Van Basten went to console his player in hospital, alongside the captain Edwin van der Sar and Van Nistelrooy. Initially, the coach intended to release Boulahrouz from the squad and let him grieve privately with his family. It soon became apparent, though, that the defender himself intended to continue and his wife wanted him to do so too. Senior players – particularly Van der Sar and Van Nistelrooy – insisted that the decision had to be sensitive and the management allowed Boulahrouz himself to make it. He immediately returned to training and declared, “I am ready to play if the coach picks me”.

Then another controversial decision was to be made. Should Boulahrouz’s daughter be commemorated publicly? The player didn’t think that was necessary and later admitted that the support he got felt like “a bit of water on a forest fire”. Nevertheless, a minute’s silence ahead of the game and wearing black armbands were considered, with the latter option eventually chosen. In retrospect, it was heavily criticised in Dutch press, and was seen as a psychological blow that affected the players’ performances. The whole affair became known, rather weirdly, as the “Boulah factor”.

Van Basten was also accused of making the wrong decision in another, very different, dilemma. With top spot in Group C assured after just two matches, he fielded a weakened line-up for the third fixture, against Romania. Victor Pițurcă’s team achieved respectable draws in their first games, and needed to beat the Dutch to progress. Klaas-Jan Huntelaar and Robin van Persie scored in a 2-0 win, but there were a sense of momentum lost.

Van Nistelrooy, Sneijder, Rafael van der Vaart, Van Bronckhorst, Nigel de Jong, Joris Mathijsen, Andre Ooijer and Van der Sar all went eight games without a game before facing Russia. Hiddink’s side, by contrast, achieved their decisive win over Sweden just three days before the clash in Basel. That was supposed to be an advantage for the Dutch, but that’s not how it was seen in the Russian camp.

Mention resting stars in a seemingly meaningless game to an average Russian fan, and he would immediately say it’s a bad idea. Even younger generations of supporters have heard a lot about Valeriy Lobanovskyi’s choice to field a weakened team against Canada at the 1986 World Cup. The Soviets had been brilliant in the 6-0 demolition of Hungary and the 1-1 draw against France in their first two group games, keeping up an incredible tempo in the Mexican heat, and the great coach gave his exhausted Dynamo Kyiv players a break in the game that was considered winnable with any line-up. The USSR did beat the Canadians 2-0 to top the group, but the rest proved to be counterproductive and Lobanovskyi’s side lost 4-3 to Belgium in the last 16.

That fiasco, remembered for dismal refereeing, was especially painful because the Soviets had a decent chance of winning the trophy. They went even closer at Euro 88 before losing to the Dutch in the final, but then the empire broke apart and the Russia national team struggled to fulfil its potential. They were never even close.

Their 1994 World Cup campaign was destroyed by the decision of key players, including Andrei Kanchelskis and Igor Shalimov, to boycott the tournament.1 Internal squabbles ruined their chances at Euro 96. Russia failed to qualify for the 1998 World Cup and missed out on Euro 2000 too. They failed miserably at the 2002 World Cup despite a relatively easy group and were sent packing early at Euro 2004 despite becoming the only team to beat eventual champions Greece. And they hadn’t even qualified for the 2006 World Cup after failing to find the net in either match against Slovakia.

In short, qualifying for a major tournament was an achievement in itself. Getting out of the group came to feel impossible for Russia and expectations gradually dwindled. Russia’s players en masse were accused of lacking character and it was widely accepted that the national team was infected with a losing mentality. It wasn’t just the fans who expected them to fail, the platers did too. That was a major problem and Hiddink’s arrival was seen as a possible cure.

The Dutchman agreed to become the first ever foreign coach of Russia in April 2006, but officially took over only after the World Cup, where he led Australia to the last 16. By then, Hiddink had been widely hailed as a magician, especially as far as national teams were concerned. He guided South Korea to the semi-finals at the 2002 World Cup. He helped the Socceroos to qualify for the tournament for the first time since 1974. In both cases, he succeeded largely thanks to building positive mentality and self- confidence – and that was exactly what Russia wanted and why they gave him a contract worth €2million per year.

Hiddink did become a magician in Russia, but it took time. When Israel scored a late equaliser in Moscow in October 2006, qualification for Euro 2008 from the group that included England and Croatia seemed a long way off. The Croats were cruising and when England beat Russia 3-0 at Wembley in September 2007, it became clear that a win against Steve McClaren’s side at the Luzhniki a month later was absolutely necessary.

Few had much faith in the team before the game, and fewer still when Wayne Rooney put the visitors ahead in the first half. But Russia suddenly began to play after the break and the substitute Roman Pavlyuchenko scored twice in four minutes to secure a 2-1 win. Russia only needed to beat Israel and Andorra in November to finish ahead of England. “We just shouldn’t shit our pants in Israel now,” the Zenit midfielder Konstantin Zyryanov said after the game. “That would be very much like us.”

And sure enough, something did go wrong in Tel Aviv. Russia did lose, conceding a winner in injury-time. Omer Golan, the journeyman striker, briefly became a celebrity and was offered a Mercedes by a multimillionaire, before learning that it would be illegal to accept. “Our hopes had been ruined,” wrote Sport Express. “Now we have to thank the team that it enabled us to dream for a month, but they shouldn’t have woken us up in such a sadistic fashion.”

The Hiddink fairytale could have ended there, but there was one more twist to come. Four days later, as Russia scraped a 1-0 win over Andorra, England, needing only a draw against Croatia to go through, lost 3-2 in the Wembley rain. Russia were through. Hiddink had been incredibly fortunate and Russia understood that sometimes in football things could go their way. Miracles could happen.

But there was nothing then to suggest what might happen in the summer of 2008. Nor was there in the spring friendly against Romania, lost 3-0. But before the tournament Hiddink made two revolutionary changes. Firstly, he redeployed Yuri Zhirkov, one of the best attacking talents in the country, as a left-back. Secondly, he unexpectedly recalled the veteran midfielder Sergey Semak, who hadn’t been used during the qualifiers, and installed him as captain. The former CSKA Moscow playmaker had been converted into holding midfielder by Leonid Slutsky at FK Moskva and flourished following a move to Rubin Kazan. “Semak is an intelligent player,” Hiddink said. “I like defensive midfielders who are not just destroyers, but are capable of creating.”

Another crucial call was to include Andrey Arshavin in the squad. The Zenit prodigy was sent off in Andorra for retaliation and was subsequently suspended for the first two matches at Euro 2008. If Russia were to go out at the group stage, Arshavin would only take part in one fixture against Sweden, but Hiddink had absolutely no doubt about him. The versatile attacker was the team’s brightest star and thus indispensable.

“This team will play without fear,” Hiddink said, something exemplified by his own willingness to take bold gambles. Russian players used to be feel immense pressure ahead of major tournaments – and therefore were afraid of losing. With Hiddink, they were relaxed and aspired to win. Even the major blow of losing the striker Pavel Pogrebnyak to a knee injury just before the tournament, didn’t affect the positive mood.

In fact, Pogrebnyak made an important contribution to the campaign at the beginning of May when his brace helped Zenit to thrash Bayern Munich 4-0 in the Uefa Cup semi-final. That was one of the best performances by a Russian club in Europe and Zenit went on to win the trophy, beating Rangers 2-0 in the final. Dick Advocaat, who also led Zenit to the championship in 2007, was part of the so-called “Dutch revolution” in Russian football. By beating Bayern in such an emphatic fashion, Zenit proved beyond doubt that Russian teams could take on the best foreign sides by playing open attacking football – just as Hiddink wanted.

Although Russia lost 4-1 to Spain in the opening group fixture in Innsbruck, they had played reasonably well. Fortune wasn’t on their side and they were at times outclassed, but they weren’t afraid – and that was hugely important. Greece were then totally outplayed in a 1-0 win. Russia needed to beat Sweden in order to qualify at their expense – and did so playing stunning football. Pavlyuchenko opened the scoring in the first half, Arshavin was immense and found the net after the break, Zhirkov was unstoppable on the left flank, Zyryanov and Semak were imperious in midfield, Aleksandr Anyukov constantly joined attacks on the right wing.

It was enough to listen to the Swedes in order to understand the quality of Russia. “They have good chances of beating Holland,” Fredrik Ljungberg said, while Henrik Larsson observed, “The Russians are playing as though they were Dutch.”

That was the best way to put it. Russia had produced much more ‘Dutch’ football than the Dutch themselves during the group stage. Van Basten’s side might have won all three matches, scored nine goals and conceded just once, whereas Russia scored four and conceded four, but the other data showed a completely different picture.

Hiddink’s team attempted 45 shots in their three matches, while their opponents only had 38 attempts. The Netherlands attempted 41 shots and their opponents had 43 attempts. Russia had 27 corners, as compared to just seven for the Netherlands. The Russians won more tackles than the Dutch and spent more time in their opponents’ half. In short, Russia attacked more and aspired to control the games more than the Netherlands. Van Basten was cautious against Italy and France, and achieved convincing results thanks to remarkable finishing on the counter. Russia were much less clinical in front of goal and wasted a lot of chances, but their performances were much more positive as a whole.

The percentage of chances taken is naturally correlated to the quality of attackers, but luck also plays its part: Russia struck the woodwork three times in the group stage.

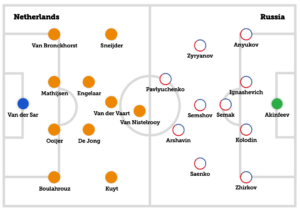

Van Basten knew Russia’s quality as well as anyone which is why he instinctively reacted with even more caution. Some pundits in the Dutch press expected the team to gamble and leave out the holding midfielder Orlando Engelaar in favour of a more creative player, but the coach was never going to play without his defensive minded stalwart. He wasn’t even sure that Robben should start, but then the decision was made for him. The winger aggravated a groin injury the evening before the quarter-final, and was eventually declared unfit to play. Van Persie was benched, meaning the Oranje only had two truly inventive stars on the pitch – Sneijder and Van der Vaart.

By contrast, Russia again fielded an adventurous line-up. Hiddink made just one change to the side that had beaten Sweden and it was arguably attack- minded, with the natural winger Ivan Saenko replacing the more conservative midfielder Diniyar Bilyaletdinov on the right. The idea was to prevent Van Bronckhorst breaking forward too frequently. Little such danger was expected on the other flank from Boulahrouz.

Russia’s players had no full-on training session between their final group game and the quarter-final, but relaxed and recovered. “Russia are one of the best prepared teams at the tournament physically,” said the squad’s Dutch fitness coach Raymond Verheijen. “The progress over the last four weeks has been huge. I am absolutely certain that there will be no problems, even if we have to play 120 minutes.”

He was right, and that was evident from the beginning until the very end. Russia looked fitter, hungrier, more determined and more confident than the Netherlands. They strived to control the ball, moved it quickly and to a tactical plan. Zhirkov was unstoppable on the left, as he had been throughout the tournament. Semak was the leader in midfield, Zyryanov distributed the ball cleverly, Semshov’s work rate was remarkable and Arshavin enjoyed the free role Hiddink gave him behind the target man Pavlyuchenko.

With the Dutch disorganised, Russia troubled Van der Sar again and again. The 37-year-old keeper had announced his intention to retire from international football after the tournament. Knowing the evening could be the last in his Netherlands career he made save after save.

After just six minutes, he kept out a magnificent Zhirkov free-kick from the right. A minute later, he saw a powerful shot by the stopper Denis Kolodin deflected wide. A few seconds passed and Pavlyuchenko suddenly was free from a Semshov cross. Hiddink even started celebrating on the bench, but the striker headed wide and the coach smiled to himself. The group games had showed that Russia had significant problems converting their chances; the only way to win was to keep producing them.

The Netherlands’ first opportunity didn’t arrive until the 19th minute when Sneijder expertly went by Anyukov in the penalty area but saw his shot blocked by Sergey Ignashevich. The Real Madrid midfielder didn’t touch the ball frequently enough, and his teammates were even less effective – particularly Dirk Kuyt who was lost on the right flank. Eventually, Van Basten moved the Liverpool forward to a central role, shifting Sneijder to the right and Van der Vaart to the left, but that set- up looked even stranger.

In the meantime, Russia kept attacking. Arshavin sped away on the counter- attack and sent a low shot towards the far corner – but the Manchester United keeper saved brilliantly. A minute later, he had to parry another fierce long range shot from Kolodin. Then the Dinamo Moscow man let another one fly – this time just wide. The centre-back made a lot of mistakes in the opener against Spain, but Hiddink trusted him, and his confidence skyrocketed.

Eventually, towards the end of the first half, Igor Akinfeev had to make a couple of saves from Van Nistelrooy and Van der Vaart and that gave the favourites hope. Although they had been outplayed for 45 minutes, the game was still goalless and luck was still on their side. In an attempt to diminish Zhirkov’s effectiveness, Kuyt was replaced at half-time by Van Persie, who was instructed to play on the right, and the message was clear. The Netherlands intended to win more balls in their opponents’ half and use their speed. But Russia proved better more organised defensively than Italy and France.

The Dutch also tried to intimidate their opponents. Van Nistelrooy elbowed Semak, and immediately afterwards Boulahrouz was booked for a heavy tackle on Arshavin. That was the end for the unfortunate right-back, though, as he was injured himself and replaced by John Heitinga after 54 minutes. Van Persie then used an elbow on Zyryanov and was also yellow-carded.

Arshavin put a free-kick marginally wide and it became evident that Russia were not bothered by the aggression. They continued playing crisp free-flowing football and were finally rewarded. With Heitinga yet to settle into the game, his flank was exposed. Arshavin dropped into midfield and provided a magnificent ball for Semak who unexpectedly popped up in space on the left. The captain sent a superb low cross into the penalty area, where Pavlyuchenko met the ball ahead of Joris Mathijsen to send it past Van der Sar.

For the first time in the tournament the Netherlands were behind and had to be proactive, but Russia continued to call the shots – and were dangerous on the counter as well. Arshavin ran away once again and found Saenko, who cut in and shot wide. On the other side, Van der Vaart was booked for protesting and Sneijder’s frustration grew with every passing minute. Van Basten then decided to use his third substitution relatively early – Ibrahim Afellay replacing the lanky figure of Engelaar.

Some pundits had advocated for that from the start, leaving Nigel De Jong as the only defensive midfielder. But that left Arshavin and Zyryanov even more space, and Hiddink decided to make a bold substitution of his own, bringing on the Bilyaletdinov for Semshov.

That was a gamble – but not the only one. Russia kept sending players forward and after 70 minutes it was Anyukov, the right-back, who found himself in a scoring position, forcing Van der Sar to make a fine save. Immediately afterwards, Arshavin’s inviting low cross almost found Saenko who was a split second late.

The best Dutch attack occurred after 71 minutes and Kolodin was booked for fouling Van Nistelrooy on the edge of the penalty area. As Sneijder prepared to take the free-kick, Van Persie stole it from him – and smashed the ball high into the crowd. Furious, Sneijder sent another shot wide himself a few minutes later. Finally, Van der Vaart managed to get one on target, but Akinfeev made an easy save. Time was running out and the Dutch could create nothing but speculative shots from distance.

In fact, they had Van der Sar and luck to thank for still being in the game at all. The keeper denied Pavlyuchenko after the striker stole a ball near the penalty area. Then, Saenko was replaced by the energetic Dmitri Torbinski. “He is not as effective in attack as we would have wanted,” Hiddink had said of the Lokomotiv Moscow midfielder before the game. “We are going to help him, because he wants to learn.” At a crucial time, he was willing to give him a go and that was an inspired decision. Within minutes, Torbinski very nearly finished a fine move started by Zyryanov and Zhirkov on the left.

In the meantime, Sneijder kept shooting wide from every possible range and screaming at his teammates. It all seemed futile until, with just four minutes remaining, he finally found his moment. He delivered a perfect free kick, Van Nistelrooy stole ahead of Ignashevich and left Akinfeev no chance with a trademark header, equaling Cruyff’s record of 33 goals for the national team. Van Basten jumped in celebration on the touchline. The Netherlands were saved.

For Russia it seemed the same old story. Once again, they’d failed to finish the job. Mentally, it could have destroyed them. But then, in injury-time, they caught a break. Kolodin needlessly fouled Sneijder near the corner flag and was shown a second yellow card. It was a reckless tackle and the defender’s body language seemed to acknowledge he was doomed, like his team. But the assistant referee Martin Balko raised his flag. The Slovakian referee Ľuboš Micheľ ran over and after a brief consultation rescinded the red card; the ball had gone out of play before the foul.

Fitness was on Russia’s side as well. Verheijen’s prediction was correct because he knew the work had been done properly. Russia outran opponents who should have been fresher. In addition, the hungriest star was wearing white. Arshavin’s suspension proved a blessing in disguise and he tore apart the Dutch defence in extra time.

To begin with Arshavin dribbled into the penalty area, but had his shot saved by Van der Sar. He then made another great run but shot high from the edge of the area. A minute later, Pavlyuchenko was much closer after cutting from the left wing and beating Ooijer – but his shot hit the bar.

Arshavin then went past two opponents with astonishing ease, but his weak shot was saved by Van der Sar once again. A few moments later, the future Arsenal man was fouled and Kolodin sent the free kick wide. Russia created chance after chance, yet couldn’t find the crucial goal.

Russia finally seemed to have found the breakthrough just after half-time in extra-time when Zhirkov – as energetic as if the game had just started – was fouled in the box by Heitinga. It was a clear penalty, but Micheľ refused to whistle, incensing Hiddink. Were they cursed? Was their extraordinary effort about to go unrewarded? When Pavlyuchenko shot wide from another tempting Zhirkov cross, it began to seem this would be another tale of Russian regret.

Torbinski was booked for fouling Van der Vaart, meaning that he was suspended for the next match. Immediately afterwards, Akinfeev bawled at Ignashevich because he didn’t like his headed back pass. Hiddink rose from the bench and told the keeper to calm down, but it was impossible to hear him. The team was approaching breaking point but, with seven minutes left in the extra-time Arshavin who decided the game.

Speedy and determined, he ran clear on the left, went pass Ooijer and chipped a cross over Van der Sar to the far post, where a stretched, sliding Torbinski turned it in from close range: 2-1. The Dutch had neither the physical nor the mental strength to find an equaliser. They were shattered, as seen when Van der Sar misplaced the simplest of passes from a goal kick and the ball went out of play. Anyukov took the throw in and Arshavin suddenly found himself in the box. He shook off Ooijer and his shot was deflected by Heitinga between the legs of the keeper.

That was that. Arshavin won. He put his finger across his lips as usual and kissed the badge. That was his greatest game for Russia and he had become one of the brightest stars of the tournament. Extra time belonged to him. “I can’t score more than a single goal for the national team,” he had said before the game. “I don’t know why. There might be a curse.” He got only one again, but Russia were through.

Arshavin kept sprinting to put pressure on Dutch in the dying seconds. He just couldn’t stop. After the final whistle, he fell to the ground – tired but happy. After exchanging shirts with Mario Melchiot, he burst into tears of joy and relief. Hiddink ran over to congratulate him. They knew that something very special had been accomplished.

On the other side of the pitch, Van Nistelrooy fell to the ground as well. He couldn’t move and remained on the pitch in pain for several minutes. The great striker has battled on in extra time, but the effort was greater than he could bear. He was the tragic figure and so was Van der Sar, who sadly applauded the great mass of orange shirts. He thought that was his last game – and it was his last tournament, even though he was later surprisingly persuaded to come out of retirement for a couple of World Cup qualifiers.

And so, 20 years after scoring his famous goal against the Soviets in the Euro 88 final, Van Basten saw his coaching career with the national team ended by the Russians. He was gracious in defeat and visited the opponents’ dressing room to congratulate them and wish them luck for the rest of the tournament. “Russia deserved to win,” he said, “because they played much better and created a lot of chances. We didn’t have the match under control and had physical problems. The players didn’t have the conditioning anymore at the end.”

“There is no explanation,” Van Persie said. “Too many guys, including myself, were not feeling right.”

“Hiddink knows a lot about us, but we couldn’t know that much about Russia,” said Van der Sar. “They kept attacking just like in the game against Sweden, because they really want to play football instead of defending. We are sadtogoout,butatleastwelosttoa very good team.”

The winners couldn’t quite believe what had happened. “I didn’t expect us to be so dominant,” said Arshavin. “It was supposed to be a difficult game and I thought we would be forced to play on the counter-attack. I also believed that we had to keep a clean sheet in order to win. Reality proved to be different. We were much stronger.”

Hiddink was especially delighted. “I am very proud of my team,” he said. We were stronger technically, tactically and physically. Our play in midfield was very good, but unfortunately we didn’t take our chances and so didn’t score in the first half and didn’t kill off the game in the second half. The Netherlands were only dangerous at free kicks and I am glad that the players didn’t lose their heads after conceding a late equaliser.”

Arshavin and Hiddink were worshipped in Russia that night as the whole country celebrated wildly. Hundreds of thousands filled the streets in Moscow and other cities and the manner of the achievement made fans especially jubilant. There was a feeling that things had changed forever. Russia were no longer minnows who suffered an inferiority complex. The Dutch magician had turned them into a force to be reckoned with. The mentality had been transformed. They were now winners, not losers. “The time of change,” was the headline in Sport Express.

The evening felt like the new beginning for Russia and end of an era for the Netherlands, but that’s not how it worked out. Russia’s brave approach and the presence of Arshavin didn’t help in the semi-final, and Spain beat them 3-0. The win in Basel turned out to be the last great chapter in Hiddink’s career.

Just 17 months after Euro 2008, Russia meekly lost to Slovenia in the World Cup qualifying play-offs. Hiddink left, the players – including Arshavin – were scapegoated once again and that psychological revolution was absent. It took Russia another decade to make it out of the group at a major tournament and that they reached the quarter-final at a home World Cup was achieved largely thanks to a very cautious and defensive approach in the last-16 fixture against Spain.

In the meantime, the Dutch kept most of the squad together under their new coach Bert van Marwijk and recovered much faster than expected. There were doubts about their style but they reached the World Cup final in South Africa and might have own it but for Robben’s historic miss in the final. The debacle in Basel is now just a distant memory for the Netherlands.

Russia’s phenomenal performance, meanwhile, proved a false dawn.

Michael Yokhin is a European football writer with a keen interest in the history of the game. He contributes to the likes of BBC, FourFourTwo, the Guardian, ESPN, Independent and Josimar. @Yokhin