Scottish Cup final, Hampden Park, Glasgow, 18 May 1991

This time next week, the final of the 139th Scottish Cup will take place. In recognition of this, Paul Macdonald revisits a classic from 33 years’ ago in issue 20

On 16 October 2015, the Tata Group announced its intention to close its last remaining steelworks in the UK, affecting sites at Teesside, Scunthorpe and Motherwell. Increased competition from cheaper territories, high energy costs and a downturn in demand were among the market conditions that influenced the decision of the Indian conglomerate. In broader terms, it hammered home the message that the United Kingdom’s proud position at the centre of the industrial universe was long gone and, for the town of Motherwell in particular, this day had been 24 years in the making.

Rewind to 1991. Margaret Thatcher may have left government a year earlier to be replaced by John Major, but her Conservative party were busy accelerating the process of closing Motherwell’s iconic Ravenscraig steel mill. Thatcher’s involvement in economic problems north of the Watford Gap was generally symbolised by rampant privatisation or closures; wealth was at the forefront of her thinking and be damned to those who happened to get in the way. Those in Motherwell who did, the men who helped establish the mill as the heartbeat of the community from its construction in 1957, were in her crosshairs.

Despite the fact that even in the months before its closure Ravenscraig remained the largest hot-strip steel mill in Western Europe, the political mechanisms had begun and like much of the manufacturing industry under Tory rule in the late 1980s and early nineties, there was little that could be done to reverse the inevitable. The protestations proved unsuccessful and by the time the plant announced its formal closure on 24 June 1992, more than 12,000 men had joined the ever-increasing dole queue. From that day forward a region made an instant decision never to vote in a Conservative politician again. To use the crass words of a North Lanarkshire constituent, “The Labour candidate could come down here, stand at the lectern, then proceed to piss on our shoes and he’d still win his seat because we aren’t going to vote for Maggie’s party, are we?”

Amid a deepening recession and with people fearful of what was to come, football, as it always seems to do in moments of oppression and insecurity, became an outlet for those stepping off the picket lines in need of escapism. Motherwell FC have never generally been worth following in order to lift your spirits; indeed, as they began their Scottish Cup campaign in 1991 with a difficult trip to Pittodrie to face the holders Aberdeen, they’d won nothing since lifting the same trophy in 1952. In the 38 intervening years, their record in the Cup was notoriously poor.

But when the forward Steve Kirk, known for his knack of arriving from the substitutes bench to strike in key moments, lashed a late winner into the top corner from 30 yards to secure progression against an Aberdeen team who would go on to challenge Rangers for the Premier Division title until the final day of the season, something felt a little different.

Motherwell were nicknamed ‘the Steelmen’ and, after a winning competition entry in 1982, had the Ravenscraig Steelworks incorporated into the club crest. The two were inextricably linked and the players, it seemed, felt obliged to provide their own support to those fighting for their livelihoods by offering some respite.

Tom Boyd, then club captain, agrees. “We were very aware of the situation at the time,” the full-back said. “There was a huge impact in terms of attendances and we knew there were massive issues in the area. We had players living locally and when we were attending events we knew how bad things were. When something of a bad nature happens, you can’t avoid or hide from it because you are reminded of it.

“From that perspective football is a way of lifting spirits and lifting morale. [Our cup run] did give everybody a lift because that’s all you can do. On the field we tried to entertain and give them a sense of purpose, success. There was a connection between the fans and the players for that reason.”

Boyd had already agreed to join Chelsea at the end of the 1990-91 season after developing into a defender of international class while at Fir Park and he would go on to make 72 appearances for Scotland in his career. For him, the Aberdeen match served as one of those moments, an injection of confidence that they could go all the way for the first time in a long time.

“We couldn’t have picked a harder tie but from there we started to get a belief,” he added. “We knew that on any given day with the squad that we had that the best form of success would be a cup run. In the league we probably weren’t consistent enough but on our day we had players that were quality and that game gave us a serious boost.”

Motherwell had talent of their own. Beyond the exploits of Kirk and Boyd, the 17-year-old youth product Phil O’Donnell usurped more experienced heads to emerge as an archetypal box- to-box midfielder, while on the wing the ageing left leg of Davie Cooper – whom Ruud Gullit, no less, included in his Dream XI alongside Diego Maradona, Johan Cruyff and Marco van Basten – was still capable of ingenuity and guile. These were individuals who deserved success but, for a multitude of reasons, had yet to experience it in their respective careers. They collectively sensed an opportunity.

In the next round the runaway leaders of the second tier, Falkirk, proved a stern test at Fir Park but Well edged through 4-2, with Kirk once again converting. Next up was Morton in the quarter-finals and after a 0-0 result at home it took a penalty shoot-out at Cappielow to separate the sides following a tense 1-1 draw. The Northern Irish midfielder Colin O’Neill drilled home the pivotal kick and Motherwell were into the semi-final, where they would face a Celtic side who had removed another hurdle by knocking out Rangers in the last eight.

A drab 0-0 stalemate at Hampden Park was as forgettable as the replay was memorable. In sodden conditions, Celtic led twice but a double from the diminutive forward Dougie Arnott pegged them back, setting the scene for Colin O’Neill to step forward once again, this time significantly further away from the penalty spot. Collecting the ball 35 yards from the veteran Pat Bonner’s goal, O’Neill took one touch and unleashed a shot that sped through the raindrops and into the top corner. As Celtic toiled to gain a foothold, Kirk emerged again, this time lofting an attempted cross that Bonner could only watch float over his head and make connection with the stanchion of his goal. It was over the line – Kirk had been the lucky charm once more. A final beckoned on May 18.

Less than a week before the showpiece the rumours and murmurings became official: there were to be redundancies at Ravenscraig. Motherwell’s manager Tommy McLean, a battle-hardened figure often parodied for his dour demeanour, couldn’t help but make the situation feel markedly worse when referencing the town’s “doom and gloom” in the build-up to the final. He paid respect to the fans travelling to the match with absolutely no clarity regarding their own futures. They would be making the short journey along the M74 for an occasion that gathered momentum and importance with each day that passed. Motherwell, as a community, needed this match. Moreover, they needed to win this match.

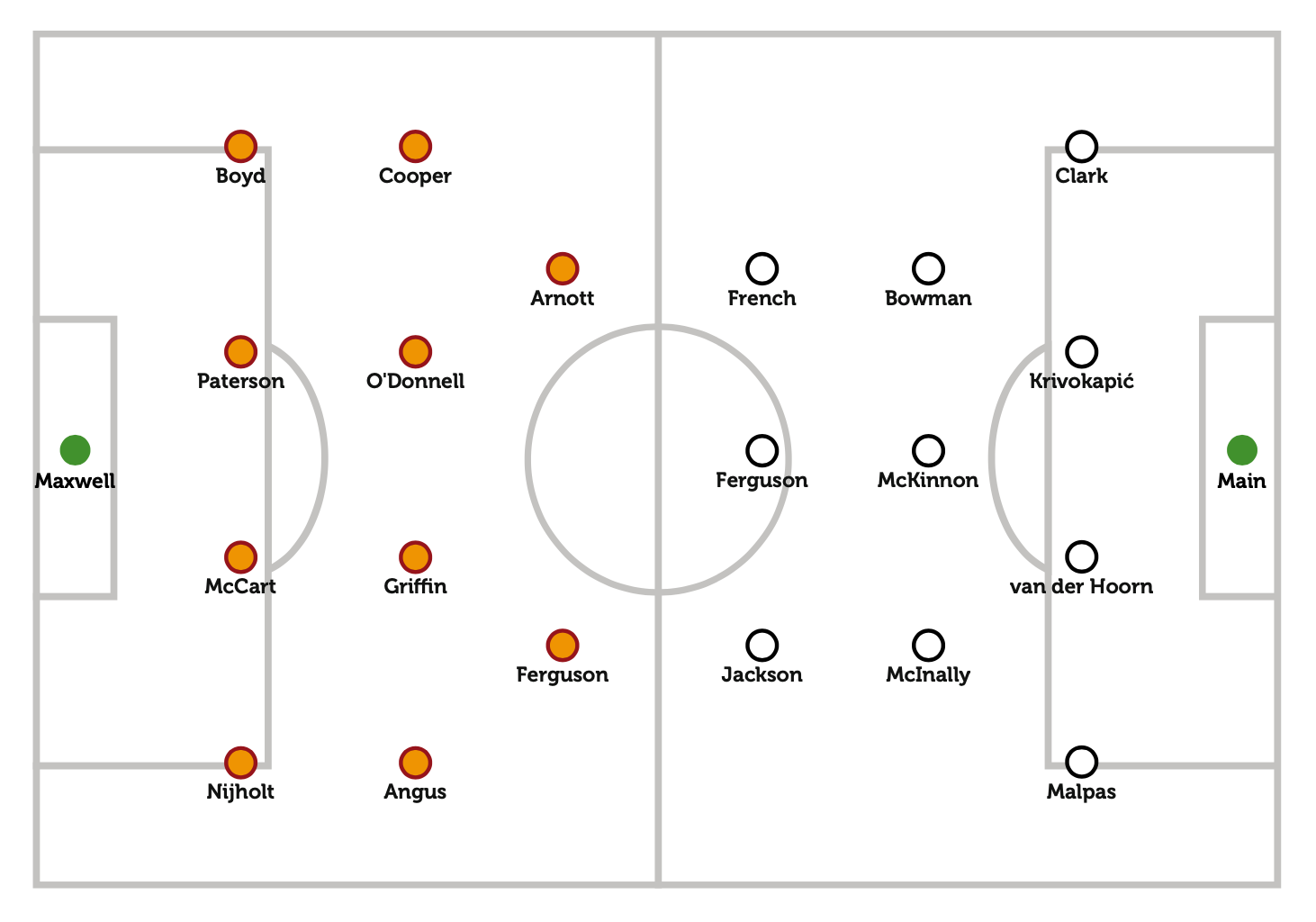

By a twist of fate, their opponents were Dundee United, helping to set up one of football’s favourite quirks – brother versus brother. Tommy McLean had helped to solidify Motherwell’s top-flight status in his seven years as manager. His brother Jim, meanwhile, was reaching the twilight of his 20-plus years transforming Dundee United from a mid-table side to European finalists. In Darren Jackson and a 19-year- old prodigy by the name of Duncan Ferguson, they had an enviable forward line and with the experience of Maurice Malpas and John Clark at the other end, many felt they would prove too strong. The one element that stood against United, however, was sheer precedent. They had reached five Scottish Cup finals during Jim McLean’s tenure and had lost them all.

57,000 packed into Hampden’s terracing, comfortably five times more than both sides combined could realistically expect through the turnstiles on a Saturday, but it all helped to set the stage for what the media gleefully called the ‘Family Final’. In reality, it needed no such hollow labelling, for those in attendance were treated to perhaps the greatest cup tie in the history of Scottish football.

United were deservedly tagged as favourites and were in the ascendency early, winning a free-kick 30 yards from goal. The Dutch defender Freddy van der Hoorn fancied his chances, striding forward with intent. As the indirect kick was knocked into his path he struck his effort low, bobbling across the surface, only for the ball to rebound off the inside of the post, roll along the line and eventually go out for a goal-kick.

The round posts had only been installed in 1987: Van der Hoorn’s pile-driver might have found the net had the square uprights still been in place but instead it allowed Motherwell to settle; the closest of close calls had calmed the nerves and with half-time approaching they snatched the lead. The striker Iain Ferguson, who had featured in two successful seasons for Dundee United in the late 80s, started the move by sweeping the ball wide to Jim Griffin and his first-time cross completed a full-length one-two with the onrushing striker, his header bulleting into the net past the static Alan Main. It was a superbly worked move and opened up a contest that had been, until that point, a battle of physicality over quality.

The half-time scoreline was 1-0 south of the border, too. The tannoy announced that Nottingham Forest led Tottenham in the FA Cup final thanks to Stuart Pearce, back in the days when the showpiece fixtures on both sides of the border were played on the same afternoon. At Wembley, Paul Gascoigne’s reckless antics had already decided his fate. Hampden had no idea the theatre that was about to come.

United took to the task of getting back into the contest aggressively from the restart as they sought to restore the dominance they had enjoyed prior to Ferguson’s opener, but John Clark was perhaps a little too exuberant in taking his manager’s motivational message to heart. Only a minute or so had been played when Clark, a giant of a defender, jumped with knee raised into Motherwell’s Ally Maxwell and clattered the goalkeeper at pace as he looked to claim a high ball. Maxwell thudded to the turf in agony, clutching his chest and signalling to the bench for assistance. He appeared to be in severe distress as the physio tended to him but the message was clear – he had to play on. There was no substitute keeper available in that era and so the alternative was an outfielder going in goal. Maxwell gingerly returned to his feet but he was clearly compromised and United knew it.

Moments later, the Andreas Brehme- lookalike Dave Bowman picked up possession at the angle of the penalty area on the right and decided to test the reflexes of the stricken Maxwell. His shot skimmed across the target and Maxwell flopped over the ball, allowing it to nestle in the corner behind him. His face was etched with pain, but it was not with disappointment at conceding – his injury was offering him genuine agony.

United sensed blood and Motherwell, with their keeper stricken, were forced to attempt to compete as far from their own goal as possible. That meant reasserting their attacking intent and their change in approach was instantly rewarded. Davie Cooper flicked a free-kick into the area, Clark’s headed clearance was weak and hung invitingly in the air on the penalty spot, where O’Donnell steamed in through flailing limbs to power his header into the corner of the net. It was Roy of the Rovers stuff – a lad born locally and who had only made his professional debut a few months previously had put his team in front in the cup final.

United were rattled, their previous five cup final defeats flashing before them as the desperation of a sixth crystallised within view. Motherwell turned the screw; Kirk, substitute once again and on to replace the goalscorer Ferguson, gathered a hopeful delivery into the area with a spectacularly adroit touch and, recognising the proximity of Ian Angus moving forward from midfield, spun the ball into his path. Angus barely had to break his stride as he drilled home with his refined left foot and, with just 25 minutes remaining, give the claret and amber contingent belief that glory was within touching distance.

But Dundee United weren’t willing to let another final slide away so easily. This was a side that, along with Aberdeen, had dominated the Old Firm for much of the 1980s and are the only side in world football that has a 100% record against Barcelona, knocking them out of the Uefa Cup in 1987. Jim McLean had instilled steel of his own and, notably, a Sir Alex Ferguson-esque volcanicity that left many a player fearing the reprisals of returning to the dressing-room with anything less than victory.

The Tangerines rallied and this time even a fully functioning Maxwell would have stood no chance. Bowman’s cross from the right was perfect, a quicksilver arc that dropped for John O’Neill, on for the ineffectual Duncan Ferguson, to crash his header into the top corner. 3-2, and with 22 minutes plus the injury time allocated for the treatment given to Maxwell remaining, an anxious Motherwell back four drifted ever deeper into their own territory, building a human wall in front of their incapacitated No. 1.

United’s attacks were frequent but were repelled consistently until the clock nudged past the 90th minute. Alan Main, ball in hand, launched his kick downfield with such gusto that it didn’t bounce until the edge of the Motherwell penalty area. The route one approach was not dealt with by the defenders Chris McCart and Craig Paterson and as the ball rose from the turf Darren Jackson was left free to jump with Maxwell, who had vacated his net. Given the condition of the latter, there was only one outcome. Jackson nodded home and set off on a manic celebration down the touchline. Maxwell slumped to the ground and McCart launched the ball into the air in anger. Extra-time beckoned.

It was clear that United held the momentum but once the match had restarted it appeared as if the exertion of the final 20 minutes, throwing everything forward with reckless abandon, had sapped their energy and as the game edged towards half-time in extra-time, Motherwell won a corner. Cooper trotted over to take it and dinked the ball into the six-yard box amid a sea of bodies. Main came to collect but the ball spooned from his grasp. It hung tantalisingly in the air as time stopped and men scrambled to claim it. It was there to be converted. Kirk pounced. The talismanic poacher followed the ball carefully and headed into the unguarded net. Motherwell were ahead for the third time.

4-3, and yet, as tired and dejected as United were, they knew that Maxwell remained vulnerable at the other end. In the second period of extra-time they laid siege to the Motherwell goal but failed to create clear chances – until injury-time arrived. A corner made its way to the back post where it dropped at the boot of the veteran Malpas. He stepped forward and caught his strike perfectly. It fizzed towards the target, avoiding all of the bodies but one. Maxwell used his last remaining ounce of energy to leap and deflect the ball over the crossbar to safety. The afflicted keeper had become the game’s hero.

The referee David Syme blew the full- time whistle to bring the most incredible of contests to an end. Jim McLean and his defeated squad congregated in the dressing-room to lick their wounds. Orange shirts exited while claret and amber remained. Some Motherwell players approached the terracing to find supporters in tears at what they had just witnessed, while others wandered around the pitch in a stupor, none more so than Maxwell, who found himself being interviewed with the trophy in hand and mind somewhere else entirely.

“I don’t remember anything about the second half,” he told the TV presenter Rob Maclean. “It was all a blur. Dizziness and double vision; John Clark, I think he caught me with his knee in my stomach, I don’t know whether I’ve torn stomach muscles but I’m lucky I can stand up just now. I’m absolutely gone.”

Maxwell had reacted on pure instinct to deny Malpas and his injuries proved to be worse than anyone could have feared. Not only had he been unable to see the ball correctly for well over an hour of the contest, he had contended with two broken ribs and a ruptured spleen. He spent the evening in hospital recovering, safe in the knowledge that there can’t be many Cup final heroes who can claim to have won the day with an internal organ on the verge of exploding.

Motherwell had done it: they had taken a town that had been weakened by external forces and given the people something to be proud of again. And yet even the halcyon memories of that day, the kind that should remain sacred and unblemished, are now forever tinged with heartbreak given the succession of tragedies that were set to befall members of the team.

In 1995, Davie Cooper was filming a coaching show for Scottish TV alongside Celtic’s Charlie Nicholas and a group of schoolchildren when he abruptly slumped to the ground. He had suffered a brain haemorrhage and died in hospital the following day at the age of just 39. Cooper arrived at Motherwell after being granted legendary status during a 12-year spell at Rangers and although it proved to be a barren period for the Glasgow giants, the winger’s languid style was offset by spectacular close control and the ability to drift past full-backs while keeping the white paint of the touchline underneath his boots. The former manager Graeme Souness believed him to have more talent than Kenny Dalglish, while Ray Wilkins referred to him as a “Brazilian trapped inside a Scotsman’s body.” That such an influential figure with much knowledge to pass on was lost impacted everyone who met Cooper and even those who didn’t.

More harrowing events were to follow. On 29 December 2007 Motherwell were facing, coincidentally, Dundee United, at Fir Park and were constructing one of the performances of the season. The captain Phil O’Donnell, returning home after spells at Celtic and Sheffield Wednesday, was in inspirational form. The occasion descended from delight into devastation when, in the 77th minute, O’Donnell collapsed after a cardiac arrest. Physios attempted to revive him as his team mates gathered around, but the 35 year old was pronounced dead 30 minutes later. The teenager who had turned the match in Motherwell’s favour 16 years previously had given his last breath for his beloved club and, adding to the despair, his nephew David Clarkson was playing alongside him. Just moments before O’Donnell’s collapse Clarkson had scored a quite stunning goal, turning deftly inside the area and, spotting the opposition goalkeeper slightly off his line, lobbing his shot with absolute precision in off the post. It would have been remembered fondly as one of the finest efforts ever seen at Fir Park were it not for the incident that followed and Clarkson admits to this day that he struggles to remember anything about the match in general.

“The game didn’t matter, I didn’t know how the score finished and I wasn’t interested. People recall things in different ways but football took a back step,” he said in an interview on the anniversary of the incident. “One thing we all remember was that we were playing some of the best football we had ever produced and everyone was enjoying it. Everyone knows how well we had done and how Phil was a part of that.”

Motherwell named its main stand in tribute to O’Donnell, repeating the gesture it had made when the terracing behind the North entrance became the Davie Cooper Stand in memory of another fallen great.

Then, just 12 months later, Jamie Dolan, a member of the 1991 squad who did not feature in the final, died suddenly while out jogging. In July 2009 another squad member Paul McGrillen was found dead in his home having taken his own life, taking the number lost to four, all of them before the age of 40.

Kirk almost became number five. The man most responsible for the 1991 Cup success was admitted to hospital while on holiday in Florida after complaining of chest pains. He was initially sent home but suffered a relapse while shopping with his wife and daughter and he was rushed into surgery where an emergency stent was fitted into an artery, saving his life.

“I was told I was very lucky,” says Kirk. “If the artery had clotted it would have burst and there would have been no way back. Obviously I look at Davie, who had an aneurism, and Phil and Jamie had heart problems. We’ve also lost Paul. You’re not safe in life. You think you’re untouchable but sometimes you have to take stock and calm yourself down. It’s very bizarre what’s happened to some of the boys from the cup-winning team.”

Too much tragedy for one club to bear, and because it is impossible to disassociate Cooper and O’Donnell in particular from the thrilling nature of the victory, the desire to honour their contribution has extended into further Cup runs Motherwell have managed. In 2005’s League Cup showpiece against Rangers, both sets of fans declared the match ‘The Cooper Final’, while when facing Celtic in 2011 the shadow of O’Donnell weighed heavy, with supporters and players alike remembering the midfielder prior to the match. It is, perhaps, these despondent build-ups that led to Well massively underachieving on each occasion, losing 5-1 and 3-0 respectively. 1991 remains the last time Motherwell held a trophy aloft.

Tom Boyd feels that some matches have too many peripheral factors that can distract players – perhaps another reason why 1991 is so unique: “Certain games have a significant impact. These occasions mean that the pressure gets to the players too much and some can’t handle living up to the responsibility. The occasion and the atmosphere can certainly lend itself to a lacklustre performance and that seemed to happen in 2005.”

In the quarter of a century since Motherwell’s Hampden heroics, the steel industry has clung on for dear life. Ravenscraig’s famous cooling chimneys and instantly recognisable blue gas tower that dominated the Lanarkshire skyline for four decades, regularly painting the sky amber as the fire from the blast furnaces smelted the steel, were demolished in 1996. However, Tata were able to acquire a chunk of what had been British Steel and retained the plate rolling works, thus securing the future of over 1,000 jobs. Those jobs remained unchallenged until Tata’s announcement in October and now the process begins again: consultancy, uncertainty… redundancy.

2016 marks the 130th anniversary of Motherwell FC. In many ways, not much has changed at all; the spectre of the remaining manufacturing jobs disappearing for good still hangs like smog from the mill, with Tata and potential government intervention keeping current employees on the brink. The football team is also in a state of flux and craving success that has been gone for too long.

Paul Macdonald is managing editor of sports websites such as Voetbalzone, Spox and Sporting News. @PaulMacdSport